“Aerodynamics are for people who can’t build engines.” It’s hard to imagine that this is the opinion of the legendary Enzo Ferrari, seeing as how cars that bear his name are some of the most aerodynamically complex creations on the road today. But then it’s also easy to understand how Mr. Ferrari couldn’t wrap his head around how far aerodynamic science would progress after his lifetime. The dark arts of downforce and aerodynamics were created for the world of motorsport, but have since made their way into the mass market, where they do more than simply push cars into the ground, amplifying grip like an invisible hand. No longer do aerodynamics consist of just rudimentary spoilers and splitters bolted on the front and back of the car, either. Today, active aerodynamics — moveable wings, ducts and vents controlled by sensors and computers — have made their way from the high-speed test ground of race tracks to extraordinarily advanced and expensive supercars to almost every segment of the consumer car mass-market.

In the mid-60s, wings were added to race cars — first in the American Can-Am series and then, more famously, on the global Formula 1 stage. Initially, aerofoils were simple and mounted directly to the body, chassis or suspension, often with one or two at the front and one large one at the back. Then, Jim Hall, Can-Am racing legend and one of the most innovative race car designers of the 20th century took it a step further with his now infamous Chaparral 2J “sucker car.” The car was powered by a monster 650 horsepower 427 cubic-inch Chevrolet engine, but sticking out of the back of the car were two fans powered by an auxiliary snowmobile engine, which together worked to suck more than 9,600 cubic-feet of air per minute out from under the boxy 2J. Combined with the effect of plastic side skirts connected to the suspension through a complex cable and pulley system, those fans helped the car generate 2,200 lbs of downforce, enabling it to take corners at a then-incredible 1.5g.

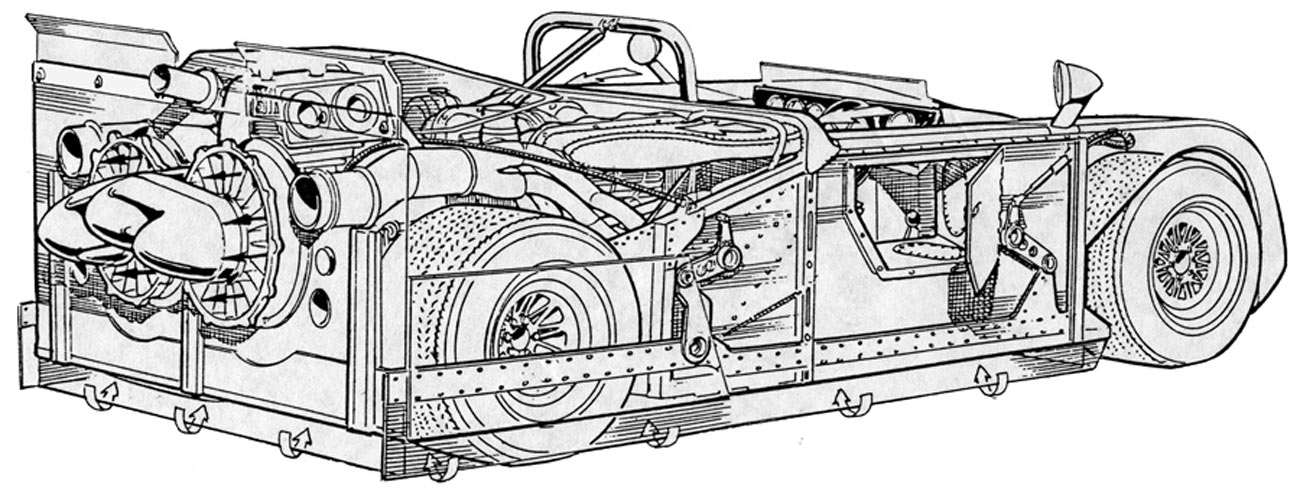

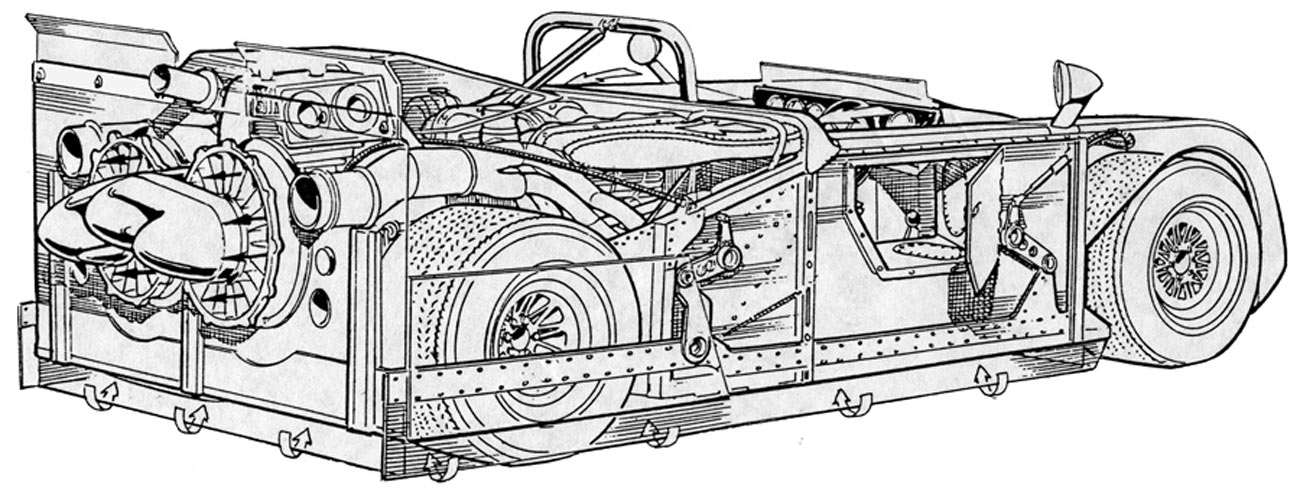

A sketch of the Chaparral “sucker car” with its two fans out back.

Despite the obvious potential of these advances, and to the frustration of the designers and engineers in motorsport, time and time again the sport’s sanctioning bodies implemented rules and regulations that killed the use of aerodynamic tricks in the name of keeping a fair and level playing field. Conversely, off the track and on public roads, while there are regulations governing how high your headlights have to be and even how big the gap has to be between the top of the engine and the hood, aerodynamics are fair game.

Outside of racing, active aerodynamics on production cars have enjoyed sporadic appearances in the mainstream market, initially appearing on what many people consider the first modern supercar, the 1986 Porsche 959. The 959 featured a speed-activated aerodynamics system that automatically lowered the car a little over two-inches at 95 mph to increase fuel efficiency and stability. For the most part, the art of channeling airflow for downforce and stability was kept to the upper echelon of performance cars.

Top-tech remains more common on cars like the Lamborghini Huracán Performante and Pagani Huayra, which sport incredibly complex active aerodynamics. Those systems consist of individual wings and flaps that raise and lower to add or remove air pressure on one side of the rear wing, tailoring downforce at each corner of the car. Though it’s been a rare sight to see active aero systems on cars the general population could actually contemplate owning, it continued for decades to happen occasionally. Both the 1988 Volkswagen Corrado and the 1990 Mitsubishi 3000GT had automatically adjusting rear spoilers, for example.

These days, you’re just as likely to see active aero as fuel saving tech on cars like the Toyota Prius.

But today active aerodynamics actually are more common than ever on more attainable cars: the Alfa Romeo Giulia Quadrifoglio and BMW 3 Series Gran Turismo utilize active rear spoilers, and companies like Mazda are currently looking into new technologies, all in the name of performance. More practical applications are widespread as well. The active grille shutters on the Toyota Prius, Chevy Cruze and a hand full of Cadillacs lower aerodynamic drag and thus improve fuel efficiency.

The Porsche 959’s simple active aerodynamics system made its way to the masses after decades, but in the automotive world, the time delta between technology development and widespread adoption is decreasing. It’s only a matter of time before the ultra-aggressive components Lamborghini and Pagani have put on the road trickle down to every family crossover. If Enzo Ferrari were alive today to see where science has steered his industry, he might revise his original quote. Aerodynamics aren’t for people who can’t build engines — they’re for people who can’t see any other way forward.