Somewhere around mile 10 I lost track of the world around me and started thinking about my GPS watch. A dull moment on a featureless dirt road that I’ve run dozens of times left me few other options. Reflecting on work woes, adventure dreams and tonight’s supper plans had got me this far, but at that moment what mattered most was the damn thing on my wrist and how it worked.

My first thought was this: I had no clue. No concrete logic or actual empirical understanding of how my Garmin talked with a dozen satellites that were (as I would later learn) 12,000 miles away. I’d heard rumors of the government launching the first satellites in the early ’80s, just a few years before I was born. Yet it was a mystery how these high-orbiting computers could communicate with millions of tiny GPS devices simultaneously, providing incredibly accurate info from far out in space.

After using my watch to navigate home, I decided to learn more. I reached out to Jon Hosler, a product line manager at Garmin who leads the development of sport watches like the Forerunner and Fenix series. Hosler oversees each watch from start to finish, beginning the process with the customer’s needs and a problem the watch will solve and working with the engineering team until it goes to mass production.

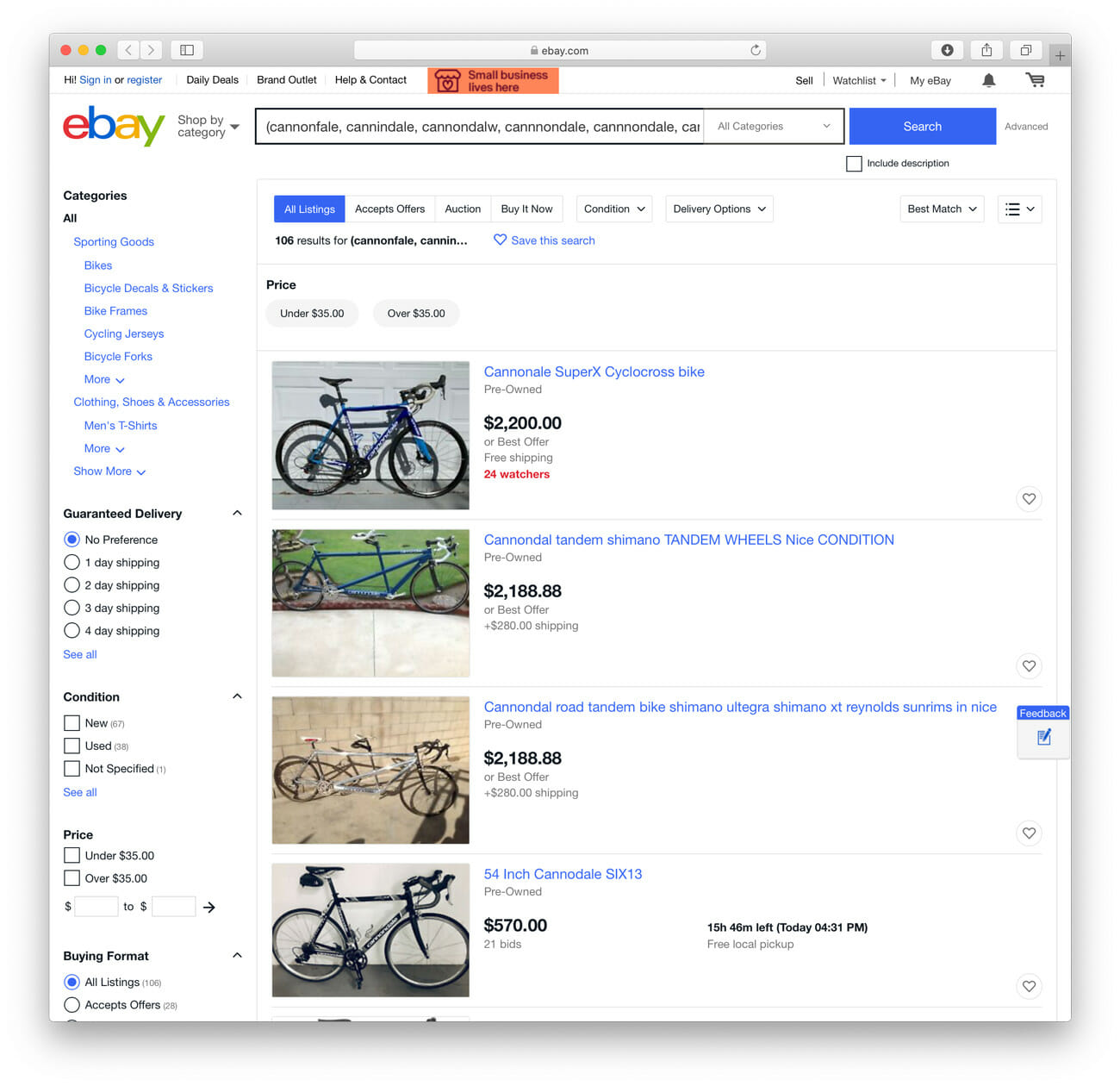

In contrast to the simplicity-oriented Apple Watch and other options, Garmin’s products have a reputation for customization. Yet all the items in the spectrum, spanning smartwatches to rugged outdoor tools, rely on the same GPS satellites. And my conversation with Hosler taught me a lot of things that forever changed how I think about the tech. Here are some highlights to amaze your friends… including an explanation of this story’s title, of course.

1. The concept dates back to at least the 1940s

The basic idea of a Global Positioning System (GPS) emerged from systems in World War II used to help ships and planes navigate at long range. The need for a global navigation system grew during the Cold War, which triggered the introduction of GPS.

2. The case does more than protect the tech

Many GPS watches use the metal watch case as part of the antenna. That’s primarily how they reduced size over the years.

3. Contrary to popular belief, GPS does not rely on triangulation

GPS watches use trilateration, not triangulation. It’s defined as “the measurement of the lengths of the three sides of a series of touching or overlapping triangles on the earth’s surface for the determination of the relative position of points by geometrical means.” In other words, GPS relies solely on distances, not angles like surveyors on a road.

The first commercially available GPS receiver, the Magellan Nav 1000, came out in 1989.

4. It literally spans the globe

GPS works everywhere on the planet, unlike some satellite systems, and in all weather. It is unaffected by clouds, rain, snow, or other inclement conditions.

5. GPS uses the same physics principle meteorologists rely on

The Doppler Effect — “the apparent difference between the frequency at which sound or light waves leave a source and that at which they reach an observer, caused by relative motion of the observer and the wave source” — is the key principle that makes GPS work. The change in frequency of signals from the GPS satellites helps in identifying locations.

6. The original GPS satellite is more than 40 years old

The first satellite was launched in 1978 and the first fully developed GPS satellite was launched in 1989. It wasn’t until 2000 that high-efficacy GPS was shared publicly, for civilian use outside the military.

7. Three are key

Three satellites are required to establish a location, but more will increase accuracy. It takes four satellites to get an elevation reading. Hosler says that 13 satellites is the average your watch sees at one time.

8. Timing is critical

Satellites travel at 8,700 miles per hour. That means time runs 7,200 nanoseconds per day slower for a satellite relative to us on Earth. This difference is important because GPS requires nearly perfect time to give you an accurate location. If not accounted for, you would be more than 7 miles off.

9. Einstein’s most famous theory plays a role

Accurate GPS time requires calculations that account for Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, which observes that while everything is moving relative to everything else, time does not pass at the same rate for everyone. For a fast-moving observer, time passes slower than it does for a relatively stationary observer, an effect referred to as time dilation. Before your head explodes, just think of Quicksilver’s “Time in a Bottle” scene from X-Men: Days of Future Past.

?

10. Other types of sensors team up with GPS

Watches use other sensors in coordination with the GPS, like a barometer for elevation, accelerometer, altimeter, gyroscope and a compass. Depending on the activity the watch is tracking, these sensors may or may not be involved. For example, if you’re running, your arms will swing and the accelerometer might not be very accurate.

11. Skyscrapers and thick forests cause trouble

The biggest challenges for GPS are big buildings with glass walls and lots of tree cover. These multipath environments bounce GPS signals and create messy data.

12. GPS satellites circle earth twice a day

GPS satellites take 11 hours and 58 minutes to orbit Earth. There are 31 total GPS satellites in orbit in six different orbit paths.

13. But they don’t last forever

Satellites eventually expire and need to be replaced. There have been 72 total launches in history.

14. The stock market depends on GPS

Because it needs to be super accurate, the New York Stock Exchange relies on GPS time, which is considered the most accurate known time. The satellites send the time to 20 different GPS control centers around earth and these provide a reference point.

15. It’s a very one-sided conversation

Not unlike your crusty old high school football coach, satellites only send data — and watches only receive.