When my editor posed this question to me, I responded with the idea that the answer could easily be some MBA candidate’s dissertation. Surely, the answer is too complicated to fit on a webpage.

Also, I wasn’t shocked to find that, despite having reported on the bike industry for over a decade, most spokespeople at bike brands, parts makers and tire manufacturers wouldn’t talk at all. Not on, or even off the record.

Think about why. The very premise of this question is that bikes are expensive. The moment you open your big fat gob, you’re agreeing that yes, paying the amount that a decent used car costs — $5,000 to $10,000 and beyond — qualifies as “expensive.”

Eventually, however, some people in the bike world agreed to discuss the question, and to defend their turf. Plus, after agreeing to off-the-record terms, an owner of a smaller bike brand came to the table with very specific advice about how most of us can save some scratch — and also harped on how the bike industry is hurting itself on costs.

So, drumroll, please! Let’s count the many ways — if not all the ways — that bikes are costly. (Yet, still, more affordable than Rolexes.)

The Rate of Innovation

Chris Cocalis is a legendary figure in the tiny sphere of bike dork-dome. He’s the CEO of Pivot Bicycles and before that ran Titus Bicycles, pre-2000. He’s a serial inventor and great at mountain bike suspension interface. Or, simply put, he’s a whiz at making mountain bike frames that pedal efficiently, feel lively on descents and steer intuitively. It’s the most complicated part of building mountain bikes, and he’s a master at it.

The bike world innovates on a pace that’s a lot closer to that of iPhones than that of motorized transportation.

He’s also a bit prickly when you tell him his gear costs too much.

Cocalis says that it’s not fair to compare cars and bicycles — or even motorcycles and bicycles — because the bike world innovates on a pace that’s a lot closer to that of iPhones than that of motorized transportation. New bike designs and bike components debut annually. Meanwhile, you can look at the suspension parts on a car, and they’ve gone virtually unchanged for years. Car body styles iterate about every three years, but engines might remain the same for a decade or more.

Also, car parts aren’t built to anything close to the surgical perfection of many bike components.

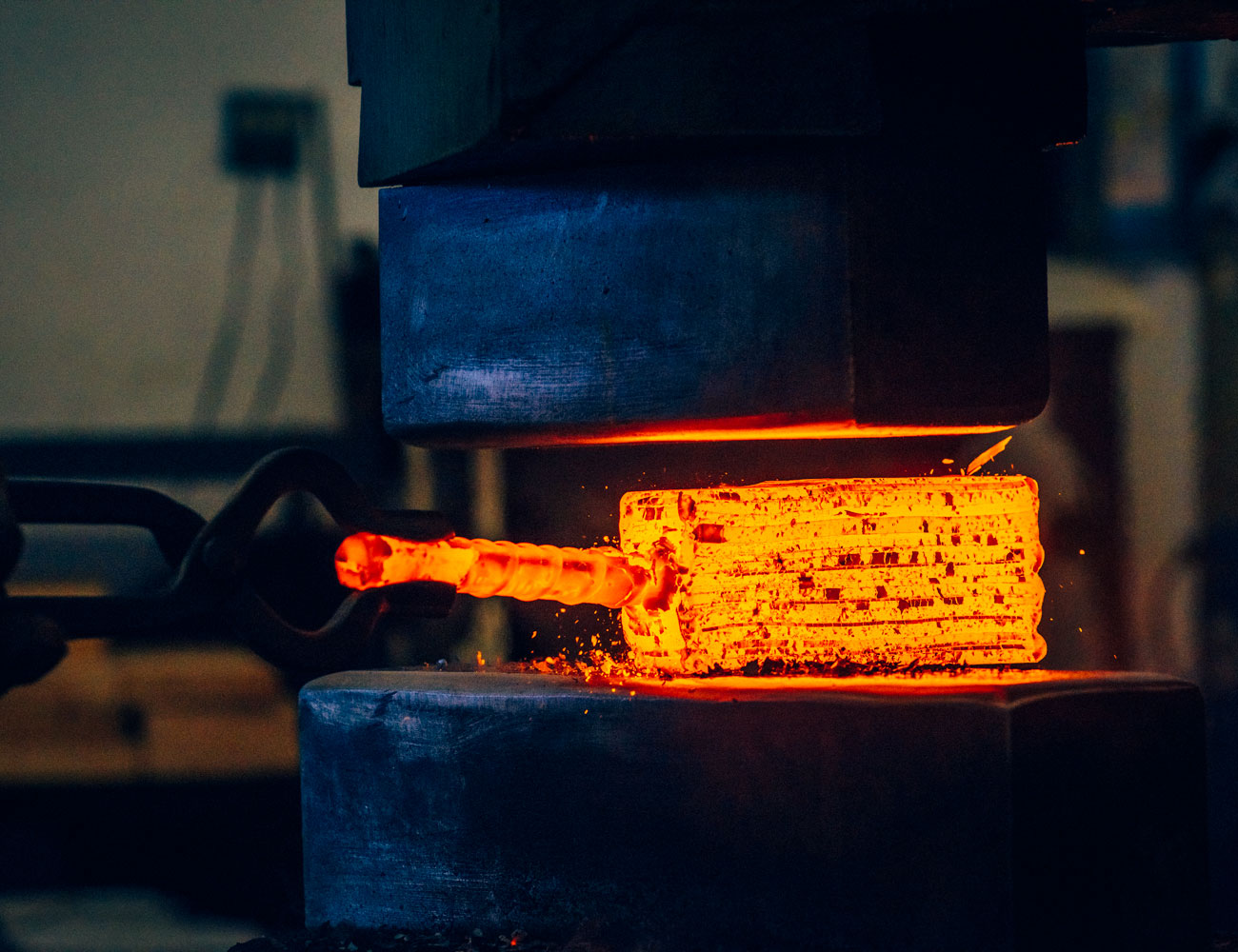

Photo: Brakethrough media

“Look at a Fox 40 or Fox 36 fork. They cost $1,000, yes, but the tolerances are works level.” Meaning, they’re manufactured to move with a far higher level of precision than you’d find from, say, a standard fork on a typical consumer-level street moto — and, of course, at a fraction of the weight. Cocalis says if they weren’t, you’d feel the difference. In a car, there’s distance between your hands and what’s going on at the wheels and rear end, but on a bike, you’re far more sensitive to the minute play in suspension. A rider can feel any slop as it robs them of power. “As with any precision product, it takes a lot more effort and cost to get that nth extra degree of performance, and the noticeable performance gain that comes from a bike over $6,000 is a relative bargain.”

When Cocalis shows someone one of Pivot’s $10,000 mountain bikes, he’ll hear some people scream, “I could buy a motorcycle for that!” Which, he agrees, is true. “But does any motorcycle with a carbon frame, carbon wheels and suspension components on par with what comes on a high-end mountain bike even exist? Yes, it does. It’s called the Ducati Superleggera V4. It matches up quite well — and it costs about $100,000.”

The Volume Issue

To get another perspective on this subject, I bounced the idea off of two experts at Specialized who are working on the electrification side of that brand, Dominic Geyer, leader of the brand’s Turbo business, and Chris Yu, the company’s leader of innovation and engineering. Yu makes the point that Specialized refused to buy off-the-rack components when it built its new Creo SL because it didn’t want an external battery on its frames. No parts-bin option existed to make an e-gravel bike that could produce 240 watts and still come in at a relatively lightweight 26 pounds.

“The development costs on that were on par with a motorcycle or even some cars because we couldn’t just buy the parts, we had to invent them,” Yu says. He also notes that one of the things Specialized is only now learning is that adding the strength of a pro rider (you, plus 240 watts) by electrifying a gravel bike has led to far higher stress loads on their top-end e-frames. “Suddenly, we’re designing bikes that have to withstand the constant force of what a pro racer only puts out when they’re hammering.”

“In many ways every high-end bicycle is like an exotic high-end car.”

This is a roundabout explanation, too, for a problem that’s relatively unique to bike building, says Cocalis, which is the constant need for customization on a small scale. Bikes, especially higher-end ones made of carbon fiber, just aren’t built in very high volumes, and yet require a ton of labor. “It takes about 1,500 people to make about 15,000 frames per year for high-end brands using the highest-end processes,” Cocalis explains.

“In many ways,” he continues, “every high-end bicycle is like an exotic high-end car.” Those 15,000 frames stack up to the rough volume of carbon fiber-bodied exotic sports cars built worldwide in a given year. And, he says, “just like the body panels and frames on these exotic cars, every single carbon mountain bike frame is made by hand in limited quantities with high tooling and engineering costs.”

Photo: Fox

Yu adds something customers seldom understand, which is that every single size of any bike has to go through the lab on its own to troubleshoot suspension performance so that every range of body type gets the most out of each bike that fits them. “What people call ‘a bike,’ is actually seven different R&D projects for us.” There’s no analog in the rest of the sports world for that cost, and it’s also why bike dealers (versus, say, backpack sellers) are in a low margin business. Most bike shops barely make a penny selling bikes. The profit is all in repair.

Watch Your Wallet

One bike maker who can’t go on the record out of fear of the ramifications, such as getting shut out of his vendor network, says that some of the costs are the fault of consumers. We’ll call this guy Fred.

“These companies aren’t dumb,” Fred says. “They know that a bike frame that’s 100 grams lighter can sell for more, even if it’s the same frame without paint. They call it ‘raw,’ and the consumer will actually spend more money on a frame that costs less to produce.”

Fred says shopping mid-tier if you’re still going to buy from the big brands, is smarter. And he says that smaller companies and direct-to-consumer brands have been successful at what’s relatively cheap (meaning $2,000 to $4,000). “Unless you’re a competitive racer, you start to get really tiny gains above that, and at a certain level, it’s all pixie dust and ‘new-car’ smell.”

Specialized’s Geyer makes another point, though, which is that somebody has to be the Tesla of the bike world. “When we made the first Turbo [in 2012], it was $6,000, but it didn’t look like any other electric bike. Now we can sell the Turbo Vado for $2,700.” Innovation costs, but Geyer argues that we’d all be stuck on heavy, clunky three-speeds if there was no market for people willing to pay for tip-of-the-spear products.

Photo: Shimano

A Small Industry with Little Competition

Fred, our silent speaker in this debate, explains that there is one cost driver that’s only going to increase — whether you’re a Specialized with huge volumes, a Pivot with more modest ones, or tiny, like Fred: drivetrains. Shimano and SRAM control the components business, with bit player Campagnolo barely a blip on their radar.

Fred says that if he wants to fit his bikes with Shimano or SRAM, every part of the drivetrain must also come from those two brands. “Even if I want to use another crank, and even if I’ve run the tests so I know that that crank might even be better, I’m forced to buy the one from one of those two companies.” Meaning that Fred can’t pick cherries. If he wants to buy their derailleurs or shifters, he has to buy the whole system.

The reason Fred believes this will only get worse is that electronic shifting is a closed protocol — Shimano’s shifters only talk to their derailleurs, ditto SRAM, etc. This is just the opposite of, say, Bluetooth, where you can pair your phone to any Bluetooth-capable device. And as these shift systems creep down in price and onto more bikes, it will become impossible for bike owners to shop for aftermarket components for their drivetrains because shifts won’t work properly — on purpose. Think of this along the lines of Apple products playing nicely only with other Apple products. In the bike space, this allows SRAM and Shimano to crowd out third-party brands. The only way a bike owner could get out of that jam would be to avoid drivetrains from the big brands entirely, another fraught endeavor.

Photo: PivotCycles

But again, Fred seizes on the caveat emptor principle — it’s up to you and me to make smart purchasing decisions. “A SRAM Rival derailleur is 46 grams heavier than Force, yet Force is a lot more expensive, and there’s zero performance benefit. When I build bikes, I don’t want to spend that money, your money, on something with so little value. I want to put it into something that actually matters.” Fred says we should think the same way. Spend more on tires, your only contact patch with the ground, or on custom wheels, where a good shop can match your weight and riding style to build something that feels great. Modifications like these can improve the feel of your present bike without requiring an expensive upgrade.

No, such frugal behavior still won’t prevent you from spending money on cycling gear. But let’s face it, we all know what we’re getting into in taking up the sport. And the hard answer to the original question is this: In a capitalist world, if great bikes could also be made for far fewer dollars, they’d already exist.

Note: Purchasing products through our links may earn us a portion of the sale, which supports our editorial team’s mission. Learn more here.