You Might Already Own the Most Disruptive Piece of Outdoor Gear

This story is part of our Summer Preview, a collection of features, guides and reviews to help you navigate warmer months ahead.

One evening last fall, I found myself after hours at King Garment Care, a dry cleaner located in downtown Manhattan. Despite a tagline that reads “Fit for Royalty,” there’s nothing remarkable about the store. Like the thousands of other dry cleaners in New York City, it has halogen lights, a white tiled floor, a wood-paneled counter and, at any given time, a conveyor of bagged button-downs, suit jackets and delicate dresses all awaiting retrieval by their owners.

On this particular night, though, the chairs and coffee table that usually populate a makeshift waiting area were stashed somewhere in the back, the halogens replaced with moody neons. And the place was packed. The long counter stood resolute as designers, social media influencers, writers, bloggers and other denizens of New York City’s fashion world bumped up against it, and instead of tailoring services, its attendant offered up cocktails encased in miniature plastic garment bags. At the back of the room, I popped a plant-based hors d’oeuvre — an imitation of a quesadilla, or perhaps a quiche — into my mouth. “Any good?” a voice to my left wondered. “Yeah, actually, it is,” I sent back, looking up to find its owner to be Alysia Reiner, who plays Fig in Orange Is the New Black.

In 2020, it might come as no surprise that such an event was held in celebration of a new app, Wardrobe. The platform allows luxury fashionistas to rent out the expensive contents of their closets for a small profit. It is, to drop an overused comparison, the Airbnb of fashion (in fact, Nathan Blecharczyk, one of Airbnb’s founders, is an investor).

Unlike similar services such as Rent the Runway, Wardrobe harnesses the sharing economy to put exclusive items in the hands of those who might otherwise not be able to afford them. Airbnb and Uber may have pushed privacy norms against the wall by letting strangers into our homes and our vehicles, but Wardrobe smashes through them by letting them into, yes, our clothing.

As ironic as the dry-cleaner setting was, it’s also key to Wardrobe’s formula. Dry cleaners serve as the “hubs” where lenders drop off clothing, and renters pick it up. They also earn a little dough themselves through cleaning fees. It’s a win-win-win. The catch? Wardrobe only operates in New York City (for now). The other catch? To lend, you need at least 20 items, each with a retail value of $250 or more. That night at King Garment Care, the only piece of my outfit to come close was my Patagonia Steel Forge Denim Jacket, which retails new for $199.

Come to think of it, nothing in my closet meets Wardrobe’s value minimum. Not unless you count down jackets or three-layer ski bibs. And yet, there’s still a place to monetize my Patagonia denim: Patagonia. The company has a program that allows customers to exchange used gear in good condition for store credit. Here, my denim jacket is worth $40.

The trade-in program is part of Patagonia’s larger Worn Wear initiative. Forever cognizant of sustainability issues, Patagonia’s aim with Worn Wear is to create a circular economy in which its gear is used over and again by multiple owners until it’s no longer fit for outdoors adventures. Patagonia isn’t alone here; in recent years, similar programs from other titans of the outdoors have sprung up. The North Face has Renewed, Arc’teryx has Used Gear and REI has Good and Used.

Each of these programs employs the same return-repair-resell model to keep everything from tents and sleeping bags to hiking shorts and technical tees in circulation. And save for The North Face, all of them rely on the same curtain-enclosed wizard to make it happen — an eight-year-old Northern California company called Trove (formerly known as Yerdle).

Trove’s space calls to mind the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Roughly 10 miles from San Francisco’s Embarcadero, Trove sits in a compact business park near the water, sandwiched between the Bayshore Freeway and San Bruno Mountain State Park. Its structure is squat and broad with relatively few windows given the roughly 40,000 square feet of its interior space. It is not a stereotypical Silicon Valley dwelling, gleaming with technological promise and replete with on-staff baristas and meditation chambers, but rather a warehouse, and perhaps an unlikely ground zero for the next great shift in how we buy stuff.

Trove’s proposition is far less complicated than its operation. The company partners with apparel and gear brands — in addition to Patagonia, Arc’teryx and REI, it also works with Nordstrom, Eileen Fisher and Taylor Stitch — to take in unwanted items, refurbish them and ship them out to new owners.

In a typical warehouse, a shipment from a supplier might contain 200 of the same exact thing, such as a green polyester t-shirt in size large. An employee unpacks the box while another stores the shirts together in a designated spot on a shelf, and when an order comes in, a third employee picks the shirt while a fourth packages it and sends it on its way. Nobody has to know where anything is to know where everything is.

It’s like finding a needle in a haystack, if the hay were also made of needles.

The steps to this dance are numbered differently at Trove. A box that arrives at 3775 Bayshore Boulevard likely has 200 different items in it, unique not just in brand, model, size and color but also in wear issues like scuffs and blemishes. How does one person organize a warehouse filled with tens of thousands of unique items so that another person, let alone an entire staff of other people, can locate one specific thing at any given moment? It’s like finding a needle in a haystack, if the hay were also made of needles.

That’s why brands as established as Patagonia and Eileen Fisher come to Trove; not for its endless stacks of boxes on shelves that call to mind the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, but for the invisible technological infrastructure the company has built to manage them.

Trove doesn’t rely entirely on backend technological innovation. Sometimes there’s a more straightfor- ward solution — like hang- tags that communicate whether a bin is full (red dot) or has space remaining (green dot).

Here’s how it works: Boxes — large ones — arrive at Trove filled with used gear. These go to receiving stations, where employees begin the inspection process by scanning each item’s tag. That taps them into the digital catalog of whichever brand, be it REI, Arc’teryx or Taylor Stitch, manufactured the item. It’s a complex integration between Trove and the companies it works with, and crucial to how the system works, particularly at the outset. It allows a Trove employee to quickly answer the question: what am I holding in my hands right now?

Inspectors check clips, zippers and other functional elements, making a note of anything amiss. (These observations eventually pass through to the item’s online description for customers to see before making a purchase.) Then the employee assigns the item a grade, from A for new to F for, well, very well-loved.

Next, gear that needs repair or additional cleaning goes through those processes. And then, in some situations, an item goes to Trove’s on-staff photographers. Individualized photography might serve to align with one brand’s way of displaying a piece, or to highlight defects.

After it’s patched up, cleaned and photographed, a piece of gear goes on the shelf to await its new owner making that fateful click. Trove uses what it calls flexible binning — employees can put any item anywhere and, by scanning its tag and the bin it’s in, it can be quickly found later, when a picker goes to fill an order.

Trove’s unique strength in the recommerce process is that it has untied the knot that forms when you reverse warehouse logistics. “We’ve managed these things at half a trillion dollars,” says Andy Ruben, Trove’s CEO. “Oftentimes, you see overly complex systems that don’t provide the value you’d expect.” What Ruben downplays is the bespoke technological systems that underpin the entire thing.

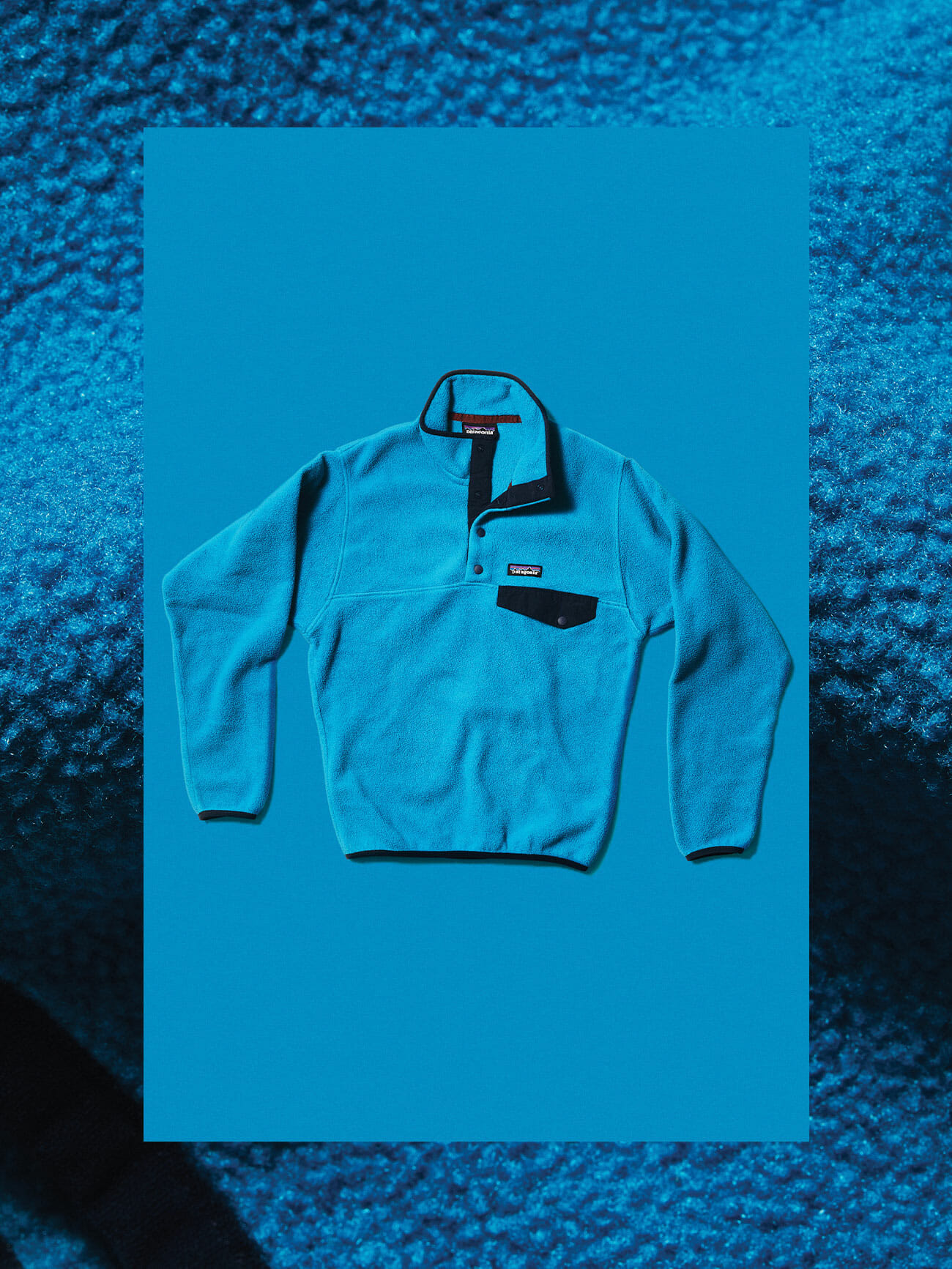

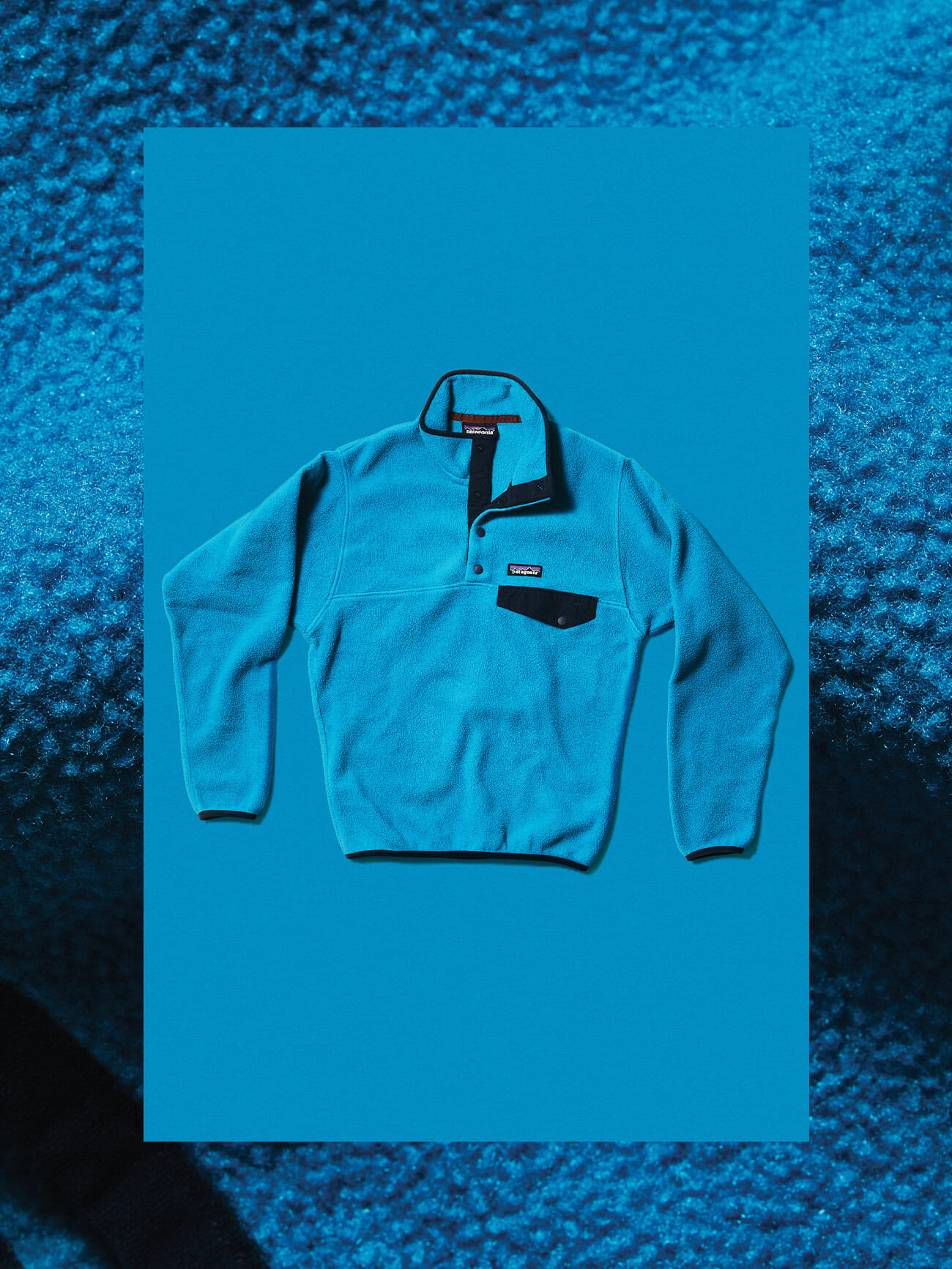

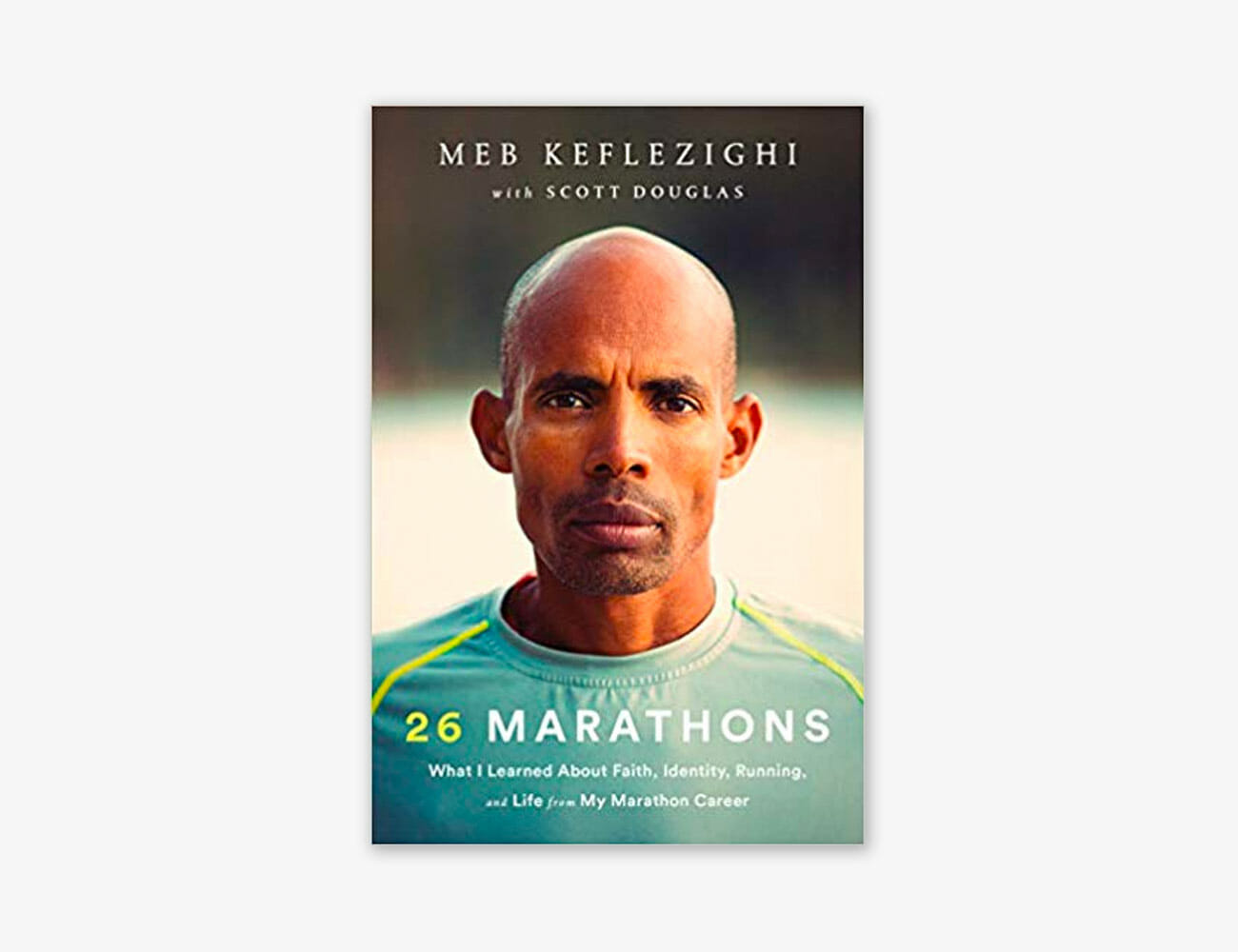

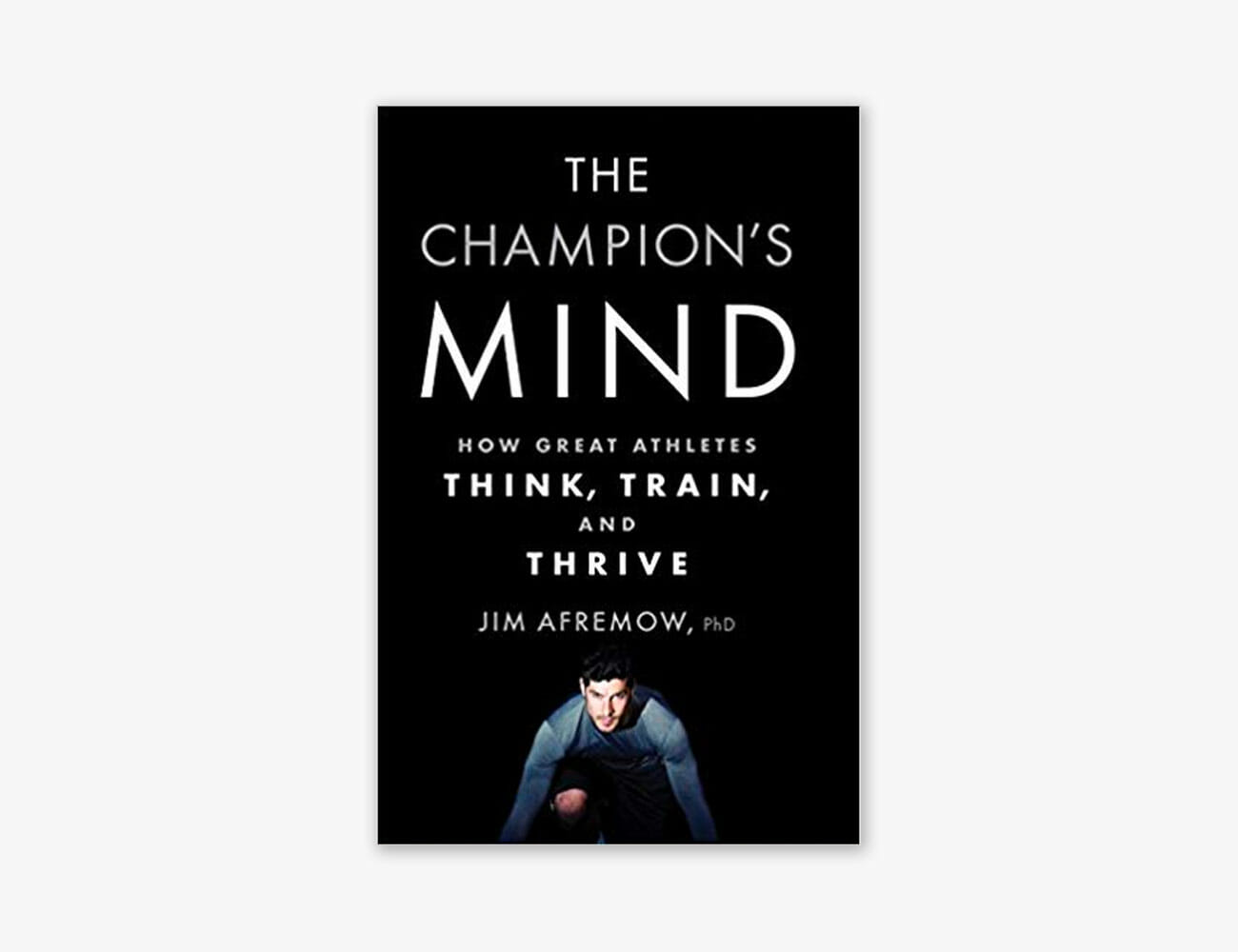

This classic blend of style and performance, Patagonia’s Lightweight Synchilla Snap-T Pullover, normally goes for $119. In used form, it’s $52.

Before visiting Trove as a guest of REI, I placed an order through REI’s Good and Used site to gear up for a two-night camping trip in nearby Pinnacles National Park as though I were starting from scratch. Nothing about Good and Used belies that it’s anything but another page on REI’s site — it looks the same and has similar menus to sift through the pile of gear available.

I quickly found myself digging deep through the digital bins in search of something unique or rare that I might not purchase at full price. It became a treasure hunt, an experience akin to sliding hangers at my local Brooklyn vintage store. After some time — the filters aren’t quite as granular as they are on REI’s main site — I checked out with my loot, which included an insulated jacket from The North Face that I’d seen Conrad Anker wear on an expedition to Antarctica. Nothing beyond a slight fading of its canary-yellow hue suggested that it had ever been worn, and it was available for $50 less than its original price.

It proved to be the ideal layer for chilly nights in Pinnacles National Park, which consists of 26,000 beautiful, federally protected Salinas Valley acres. Only miles from Steinbeck’s vision of Eden — endless avocado, citrus and garlic fields — the park forges a sharp contrast to the surrounding farmland, a high-desert landscape dotted with narrow talus caves and pillars of stone left behind by an ancient volcano and carried 200 miles north by the San Andreas Fault.

It is, by definition, an island, home to more fauna than any tropical paradise in the Pacific. Over two days, we spotted quail, lizards, tarantulas, coyotes and a threatened species of frog. We chased raccoons out of our camp and observed a flying insect called a tarantula hawk that, somehow, looks more menacing than its name already implies. The strange and thriving wilderness could be a set location on Avatar.

Still, there remains an overhanging feeling that its proximity to California’s mill of technological industry, just a few hours’ drive away, leaves it fragile and exposed. Unfortunately, this situation isn’t as unique as Pinnacles itself.

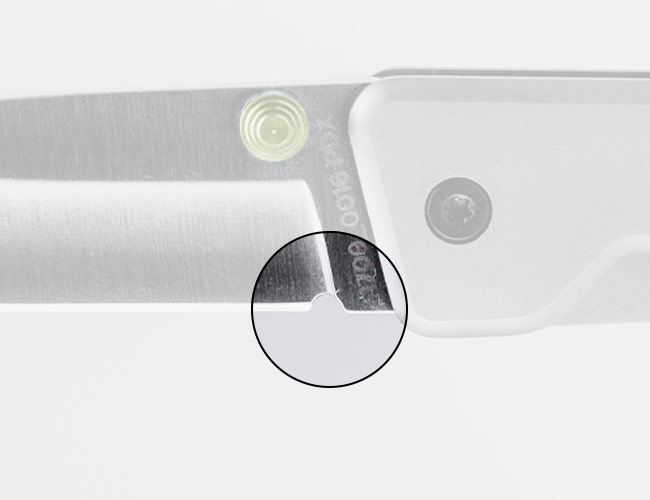

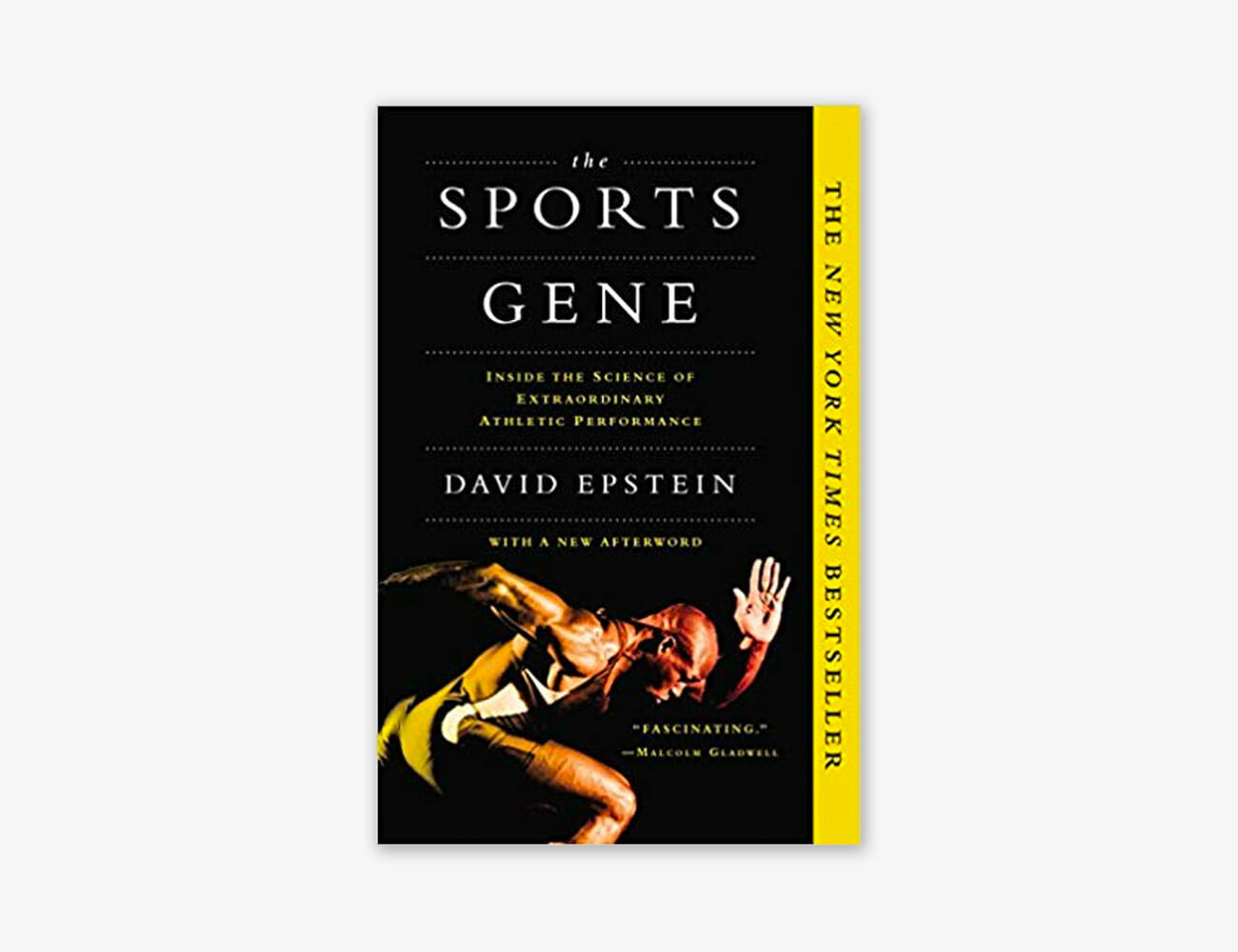

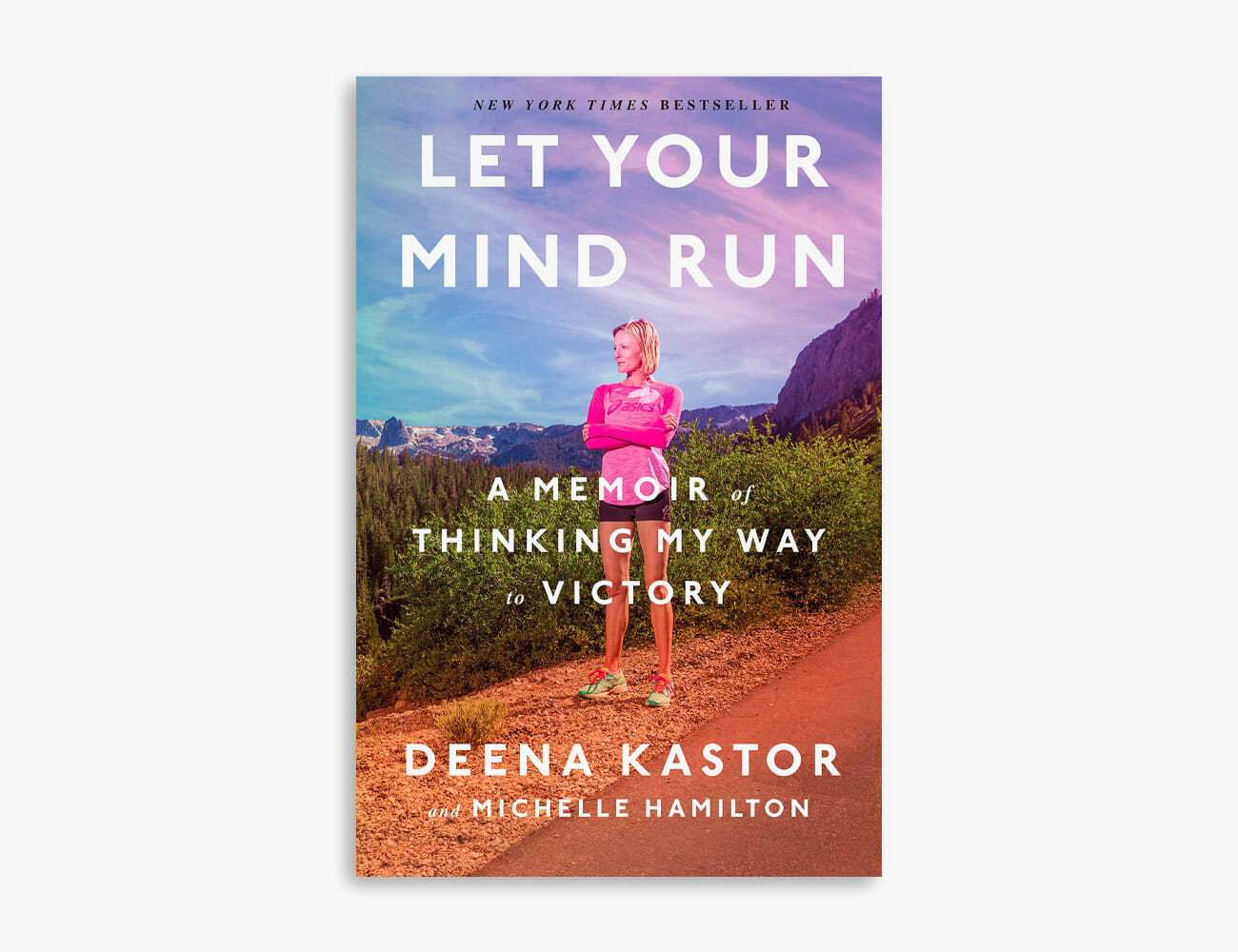

This used Arc’Teryx Consular Jacket, circa 2012, features a backcountry-ready Gore-Tex Paclite shell, fully taped seams… and a price tag of $134.

REI knows this. Its identity is wrapped in the belief that “a life outdoors is a life well-lived,” and it asserts its purpose is “to awaken a lifelong love of the outdoors, for all” — two mottos found on REI’s “Who we are” page online. The company is known for symbolic gestures such as closing on Black Friday, and more tangible actions, like setting concrete sustainability standards for every item it sells, forcing brands to comply or set up shop elsewhere.

Recommerce — collecting and re-selling used gear — is the next, and perhaps grandest, step in this mission. In the outdoor industry, sustainability initiatives like donating profits, repairing products for free or planting a tree for every item purchased abound. They are noble and worthwhile objectives, but none fully live up to their Earth-saving promise. Using recycled materials to make gear is at the top of the list, but still doesn’t prove to be the ultimate solution. For instance, a jacket made of recycled materials may still require a harmful manufacturing process — and may not itself be recyclable. That circle is broken. To “optimize the life cycle of a product with recyclability at the end of life is an important point on that closed loop,” says Peter Whitcomb, who spearheaded REI’s used gear initiative before recently becoming chief of staff at Trove.

Ruben agrees, adding that he doesn’t believe consumers are going to put up with rosy, ultimately empty claims much longer. “There’s an increasing expectation, especially with younger customers, that pushes on more innovative business models,” he says. Innovation, not in business but in the creation of new gear, might also be a result of recommerce. Shoddily made items that fail or break easily drop out of a circular economy, whereas the best things remain, like lumps of gold in a pan. “It keeps higher-quality gear in people’s hands,” observes Ruben. Recommerce highlights the things that are made well and the brands that are making them, drawing attention to the seemingly contradictory notion that something used might actually be better than something new.

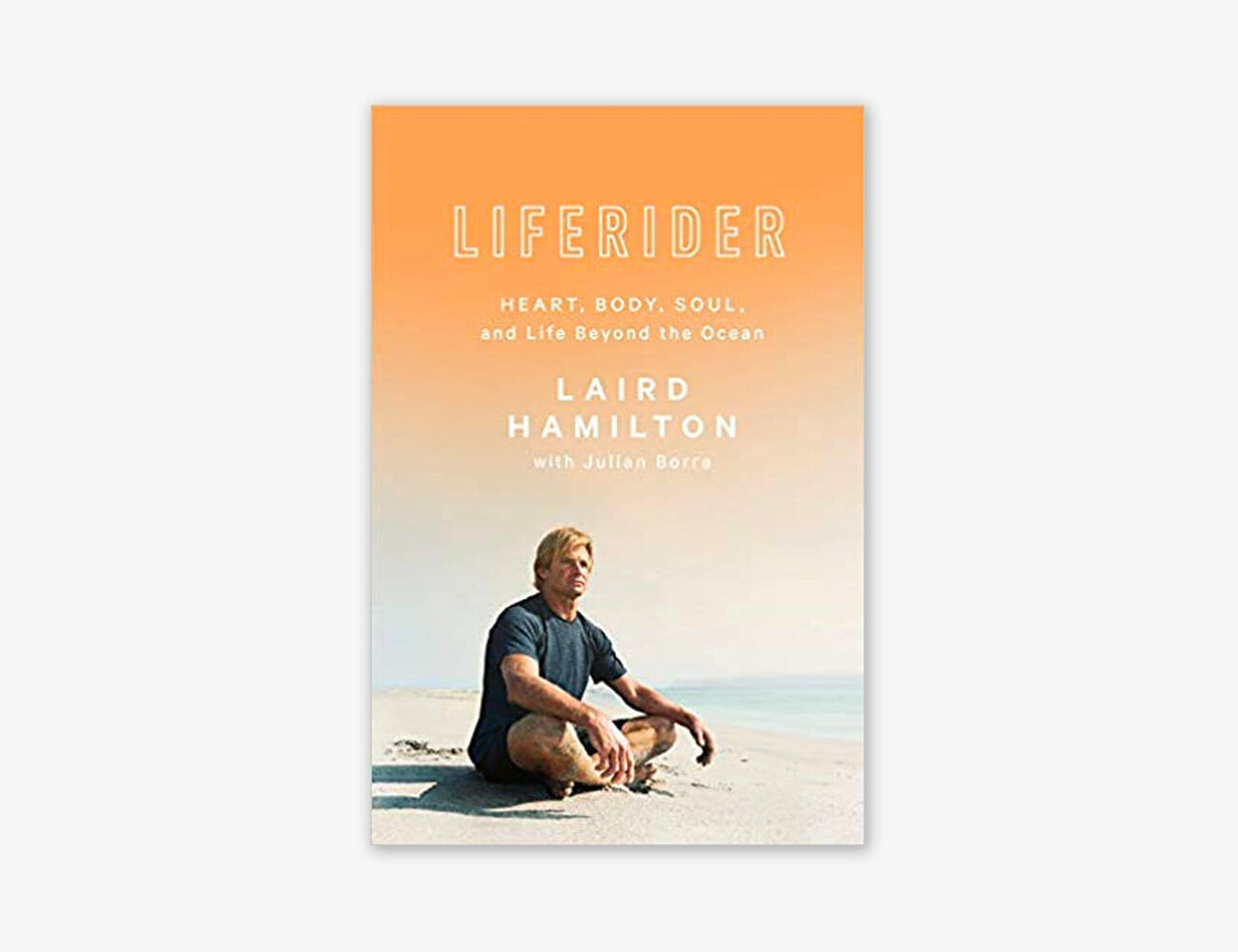

As part of its Renewed program, The North Face has clothing designers turn damaged and used items into unique pieces. This one-of-a-kind Thermoball Eco Snap Jacket costs $100.

During his tenure as REI’s director of new business development and circular economy, Whitcomb says he was often asked how the brands that REI carries react to its Good and Used program. His response: “They generally love it, because it keeps their product in use longer.” A better question might be: how does REI react to it? Isn’t the goal of any retail operation to sell as many things as possible?

“[REI] is kind of disrupting [its] own business model,” he admits. “Optically, systematically, process-wise, it’s truly disruptive and uncomfortable for a lot of people. This type of transformation is a huge challenge.” REI’s mission of promoting lifelong access to and enjoyment of the great outdoors, as well as its status as a member-owned cooperative, helps it clear that obvious barrier. According to Whitcomb, REI’s used-gear program has yet to threaten the company’s in-line sales.

The secondhand market hit $24 billion in 2018. By 2023, it’s projected to more than double to $51 billion.

That surface-level concern exists across the movement, but it’s as deceptive as a thin sheet of ice. Not only does the secondhand market not affect sales of new items, it’s also a backdoor for shoppers to access reputable brands. “By offering our Restitch items at a lesser price, the program also works as an introduction to Taylor Stitch to those who might not be able to pay the full retail price, so it’s expanding our customer base,” observes Michael Maher, CEO and cofounder of the menswear brand. “It has created an exciting way for us to follow some of our favorite pieces year after year, throughout their lifespan as they wear in, not out.”

It also doesn’t hurt that the fashion industry has already proven that selling used stuff is a pretty damn good way to make money. According to a 2019 Fashion Resale Market and Trend Report by Thredup, a digital secondhand marketplace offering clothing from over 35,000 brands, the secondhand market hit $24 billion in 2018. By 2023, it’s projected to more than double to $51 billion. Thredup, StockX, Poshmark, Rebag, Grailed, Stadium Goods, GOAT and Trove are in fact the freshmen class of companies participating in the surging secondhand wave. Long gone are the days when the only online places to save a buck on a used pair of Redwing boots or some vintage Levi’s were eBay and Craigslist.

Before founding Trove, Ruben worked at Walmart as a corporate strategist, then as chief sustainability officer and finally as VP of global e-commerce strategy. “In the late Nineties, I was part of these conversations when e-commerce was just starting,” he says. “And I remember the conversation when Walmart was deciding whether it would have its own e-commerce platform or be on the Amazon platform.” With hindsight, the answer is obvious.

That’s where Ruben believes recommerce is today. He compares the value and convenience that it provides to Spotify and Airbnb. “Ten years from now, it’ll feel the same way as me looking back at e-commerce in 1998; of course it’s that big, of course it’s the way it’s gone.”

Perhaps fittingly then, Trove shares its parking lot with The RealReal, a marketplace for secondhand luxury goods, and the first such business to go public.

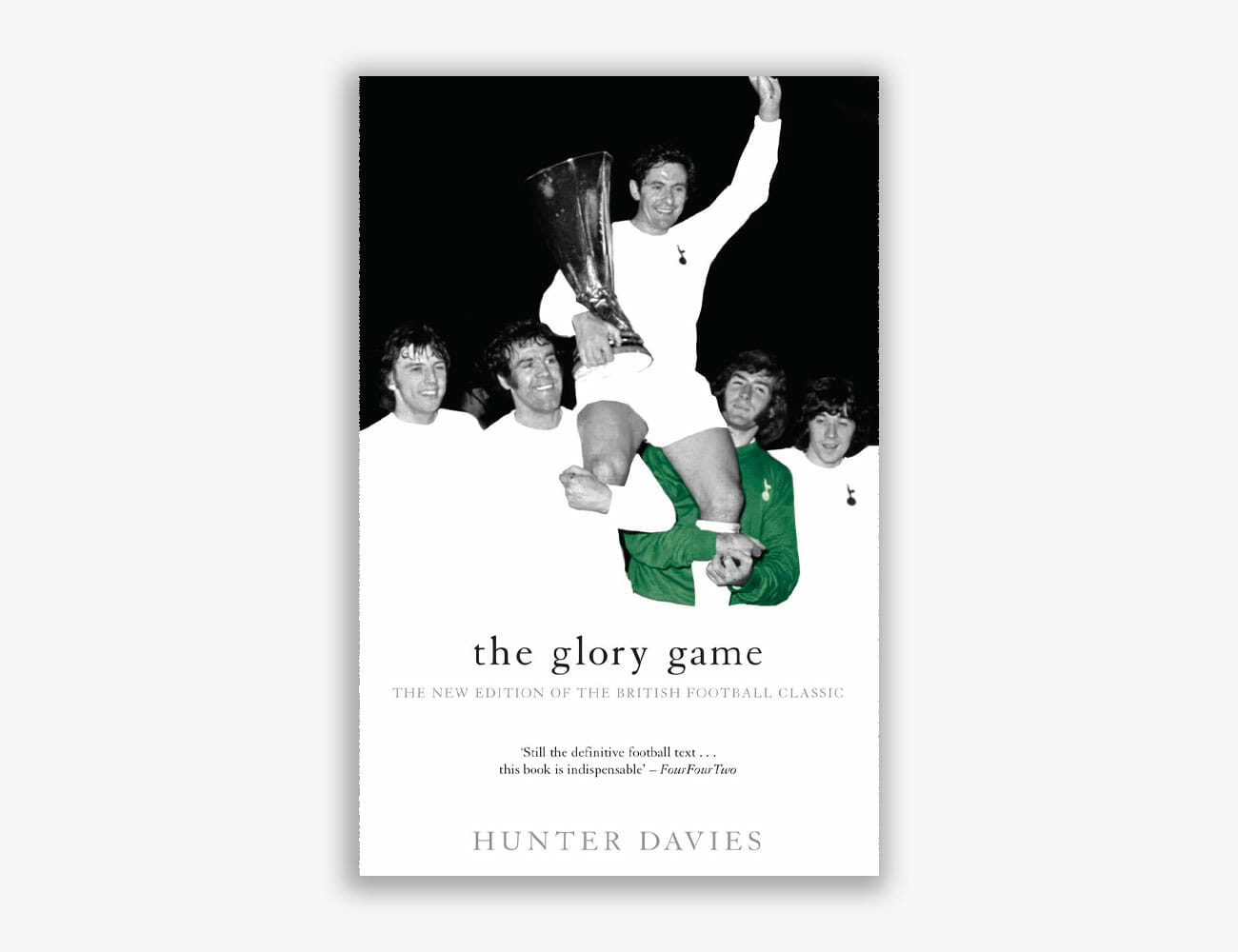

Arc’teryx built this Velaro 35 Backpack with its waterproof Advanced Composite Construction fabric. It cost $199 in 2015, but now, lightly used, it’s $139.

Ruben says that in 2018 he could count the number of applications to Trove’s program “on one hand.” Within the first half of 2019, he had 50, and whereas in the past, those applications were filed by sustainability managers, now it’s executives grasping the benefits. And since they began working with Trove, Taylor Stitch has taken in over 5,000 articles of used clothing, Patagonia has resettled over 130,000 items and REI sold nearly one million pieces of used gear in 2019 alone.

In a 2019 equity research report, Wells Fargo jumped on board with numbers of its own, stating that it estimates that by 2022, 40 percent of the contents of our closets will be secondhand buys. Surely, this is a future that neither eco-conscious outdoors enthusiasts nor trend-watching fashionistas expected. And perhaps partying at a New York City dry cleaner makes just as much sense as spending a night in the California wilds, kept awake by invading raccoons and hellish insects.

A version of this story originally appeared in a print issue of Gear Patrol Magazine. Subscribe today.