The McLaren 720S goes around a racetrack the way the Earth goes around the Sun, inasmuch as the numbers involved are very difficult to comprehend. The Earth is very large, and the sun is even larger and very far away, such that a relative speed of 67,000 miles per hour seems crazy but is barely noticeable. The McLaren, however, puts you in a more immediate frame of reference, such that everything pertaining to its speed is not just noticeable, but alarming.

The 720S is so fast that there’s no warming up to it. Almost immediately you’re driving at speeds that, in pretty much any other car would mean imminent calamity. Even the non-alarming voice the driving coach in the passenger seat uses to tell you to go faster seems alarming.

Best of all, though, McLaren reminds you that rewards come with skill, not just speed, which is weird for a car this fast. You can’t just point the steering wheel, mash the gas and let the electronics sort everything out. You have to, you know, actually drive, paying close attention to weight transfer and smooth inputs. That also sounds weird, but it’s rare these days. In our world of point-and-shoot supercars, McLaren made the 720S a true driver’s car.

So, how did we get here? In brief, after dipping a toe in the carmaking pool with the McLaren F1 in 1992 and the Mercedes-McLaren SLR in 2003, racing juggernaut McLaren started McLaren Automotive in 2010 and got into the business full time. That lead to the MP4-12C (later just 12C), P1, and eventually the three-tier Sport, Super, and Ultimate series lineup present today. The 720S sits in the middle, replacing the 650S and 675LT. Since the start, McLaren has launched at least one new model or derivative every year. So expect a variant of the 720S in 2018.

This is the first of McLaren’s second-generation regular production cars. It uses a carbon-fiber underbody the company calls Monocage II, an evolution of the P1’s monocoque that replaces the previous carbon fiber tub. It has all the things that come with structual evolution: light weight, lower side sills, higher rigidity. The new carbon monocoque also results in amazing rear visibility, thanks to a C-pillar located at the far edge of the car, bolstered by another thin strip of carbon fiber with glass covering the space in between.

Visbility also benefits from the fighter-jet profile of the 720S. The wedge-shape of the previous McLarens gives way to a canopy-like roof that recalls cars like the Pagani Zonda or original Acura NSX. McLaren goes a step further by folding the air inlets for the radiators into the doors, so that you can’t see them from the side of the car.

Every crease and curve in the 720S leads to some kind of aerodynamic function. And then there are the eyeholes. The blacked out area in the nose houses the daytime running lamp light bar, the headlights, and inlets for more heat exchangers. The motivation was to avoid having more inlets that disrupt airflow or make the styling too fussy. In person, they’re fine. Otherwise the 720S is a beauty of sweeping, organic shapes. It makes the previous McLaren cars, which were attractive in their own right, look heavy and dowdy.

Open up the out-and-up hinged dihedral door and climbing to the 720S is easy, provided you’re not interacting with the optional racing buckets. Those seats have a deep hip bolsters, which makes exiting about as elegant as getting up from a bean bag chair. On the plus side, they’re nearly as comfortable as the standard seats and more supportive in hard cornering, which the 720S does well and often. The rest of the cabin is familiar McLaren territory with a couple of parlor tricks thrown in for good fun. The main attraction is the tilting dashboard, that goes from a full digital display to a horizonal tachometer and digital speedometer. McLaren sees your head-up display, and decided it doesn’t need it. The other trick is deep storage pockets in the doors, which latch closed when the door swings up to prevent any unwanted spillage of whatever McLaren owners stash in the doors. Is it gum wrappers and receipts like the rest of us?

Anyway, fire up the 720S with the start button (make sure the brake pedal is firmly pressed, lest embarrass yourself by cycling through the on, off, and accessory modes to no effect), and the new 4.0-liter twin-turbo V8 comes to life. It doesn’t roar to life or howl, it just starts. And that’s the biggest fault of the McLaren 720S. For a $288,845 starting you don’t get much in the engine noise department. The optional sports exhaust elevates the soundtrack from bland nothingness to a nice tenor growl, but the McLaren still lacks the distinctive sound of a V8 in a Corvette, Aston Martin, or pre-turbo Ferrari.

But oh heavens does this engine go. It’s an evolution of McLaren’s 3.8-liter V8, stroked 200 cubic centimeters, with new turbos, electronic wastegrates, intake plenum, heads, crank, and pistons to list a few parts. McLaren says it’s 41-percent new. Output is up 69 horsepower, and 68 pound-feet of torque, to 710 hp and 568 lb-ft. Zero to 60 miles per hour happens in a claimed 2.8 seconds. McLaren says the 720S will do the quarter-mile in 10.3 seconds. Top speed is 212 mph.

Those numbers seem like afterthoughts to how the McLaren feels. And it’s not just the launch, it’s anything that involves forward progress. And probably reverse as well, but we didn’t try that. Stab the accelerator on an open stretch of country road and you’re up to 120 mph in a matter of a few car lengths. That move – hard gas, hard brake, maniacal laughter, repeat – never gets old. On the track the 720S accelerates with an unbelievable ferocity. As in, during the time between easing on the gas pedal and pinning it to the firewall, your brain stops about halfway down while your foot keeps moving. I did it, lap after lap, and every time found it shocking.

Yet for such power, and equally matched grip and braking performance, two things stand out about driving the 720S fast. First, the lack of noticeable electronic intervention. Even on a rough two-lane the only indication of traction control is the flashing light. There’s no bogging or surging in the engine.

The second thing about driving the 720S fast is how balanced it feels. This also conveys a hint of danger, at least at first encounter: drive this wrong and you’ll pay for it. Get accustomed to the car’s responses, though, and it floats through corners. This McLaren doesn’t oversteer or undeersteer so much as it just corrects course with the right pedal application. The only exception to this is when the rear wing pops up as an air brake at decelerations above 0.5 g and you feel a noticeable weight shift to the rear.

There are three modes each to both the suspension and powertrain: comfort, sport, and track. McLaren representatives noted the elimation of “Normal” as the default setting, which is a nice touch. Sport and Track progressively tighten up the dual-clutch automatic shift speed and loosen up the stability control threshold. Then there’s Variable Drift Control, which McLaren is keen to point out is not a magic drift mode button, but more of a variable setting to allow more and more yaw. In function it’s similar to other graduated track modes like Chevy’s performance traction management, but more oriented towards potential hoonage. You can also turn everything off for full Cars and Coffee social media embarrassment.

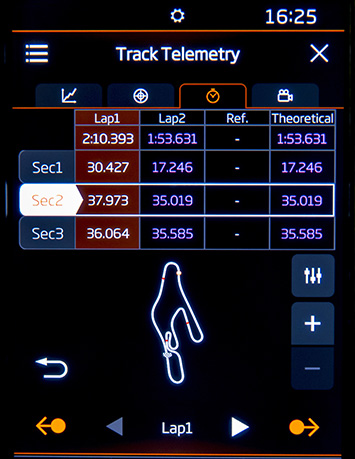

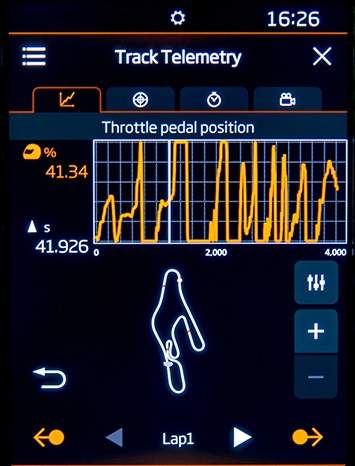

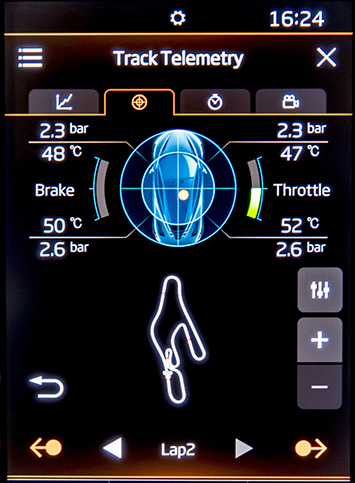

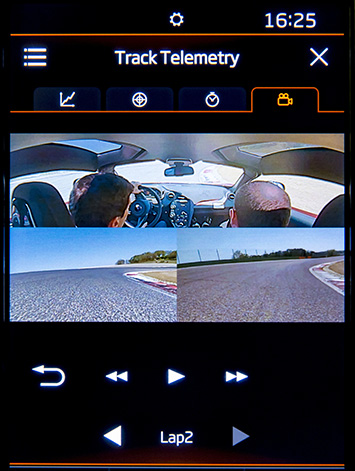

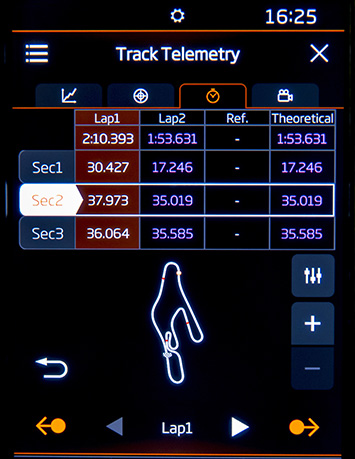

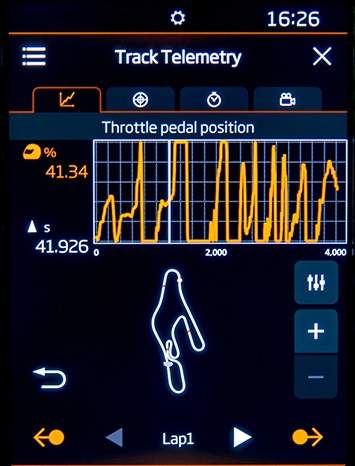

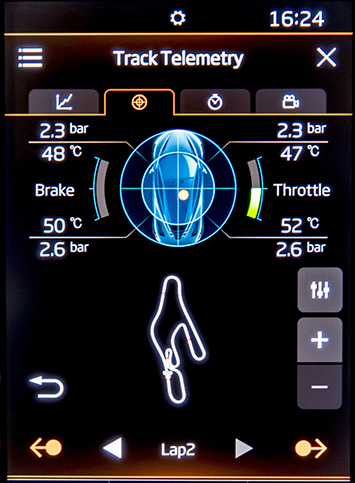

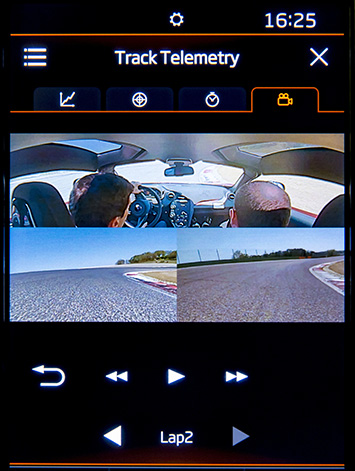

Then there’s McLaren Track Telemetry (MTT), a $2,620 option on its own or $4,220 lumped in with front, rear, and in-cockpit cameras. This is the part that makes the 720S both a driver’s car and a driving coach. MTT delivers a full suite of telemetry and lap timing, plus a split time display in the dashboard. Inside the car you can review video, look at data like speed, brake pedal force, and steering angle and compare it all to a reference lap. In my case I learned that compared to McLaren’s pro driver I chickened out on Vallelunga’s Curva Grande (duh) but did some good hard braking after the back straight (hooray for me). It will also show your theoretical fastest lap from a sessions by taking the best splits, just like in Formula one. And you can download the data and video to a USB drive for further analysis or social media embarrassment.

McLaren’s cars have always delivered an amazing combination of comfort with the performance. If there’s a unique angle to the cars from Woking, other than not being Italian, it’s that they meld all that performance with plenty of comfort. A major key to this is Proactive Chassis Control, McLaren’s name for its hydraulic suspension that moves pressurized oil between the corners of the car. The newest evolution of this adds one accelerometer and two pressure sensors in the damper at each corner. The fun fact is that the 720S does it without anti-roll bars. The practical upside is that, especially in Comfort mode, the McLaren’s ride is amazingly compliant, bordering on downright pleasant. If you long for spinal punishment, Track mode stiffens things up to barely-tolerable levels on public roads.

Along with the complaint ride is a spacious cabin, which is a surprise given how wide the doors are. There’s more than a foot more car beyond your elbow. Even for a wide car that should make for a cramped cabin, but there’s plenty of shoulder room and the abundance of glass in the cabin keeps things from getting claustrophobic. Cars this expensive that sell in numbers as few as the 720S have resale values that are tied closely to odometer mileage. Which is a shame, because McLaren a built a supercar perfect for long distances. It’s even user friendly. Whereas Ferrari makes you fuss with pulling both shift paddles for neutral, the 720S has three big buttons for drive, neutral, and reverse.

So the McLaren 720S is a car made for driving, both on the track and, well, anywhere. And you can actually buy one, unlike the obsessive vetting process for the Ford GT. It’s safe to say that in it’s short history McLaren has carved out new ground in the supercar world, both in terms of accessibility (at least to the monied) and expanding the breadth of capabilities. It’s also safe to say that the 720S is McLaren’s best regular production car yet. At least until the next trip around the sun.

On this week’s Autoblog Podcast, Editor-in-Chief Greg Migliore is joined by Associate Editor Joel Stocksdale. We talk about driving the new engines in the upcoming 2019 Chevy Silverado,updates to the Ford F-150 Raptor and a purple McLaren 720S that briefly passed through our office. As always, we also help a listener buy a new car in our “Spend My Money” segment.