The Phantom Oribe

Once you get to a point in life where you can walk into a Rolls Royce dealership and buy one of their top of the line Phantom models, you should feel a sense of achievement I guess, and if you are even able to custom order one of these flagship models with the exact options you like, that feeling gets even better, you’ll have to wait for it to be built in the UK, but in the end, you’ll have YOUR Rolls Royce Phantom, and your bank account will see a check for several hundreds of thousands of dollars being cashed … but you’ll be the proud owner of a Rolls Royce, you’ve made it in life.

But just like the world of yachts, you’ll have different degrees, and most of the superyachts or megayachts will be fully custom build to the exact wishes of the client, so you’ll either be rich … or super-rich, depending on the size of the yacht, and the people that are able to have Rolls Royce build them a truly bespoke car, with the help from one of the most famous designers in the world, will probably own one or more megayachts too, now I don’t know for sure if Japanese entrepreneur, art collector and supercar enthusiast Yusaku Maezawa owns a megayacht, but he is the proud customer for this Phantom Oribe, created in collaboration between Rolls Royce and Hermès.

This one-off gets its own, bespoke two-tone MZ Oribe Green and cream exterior finish, which was inspired by shades found in Mr. Maezawa ‘s private collection of ancient Japanese ceramics, this luxury on wheels has been specifically commissioned to complement a private jet the customer recently added to his collection.

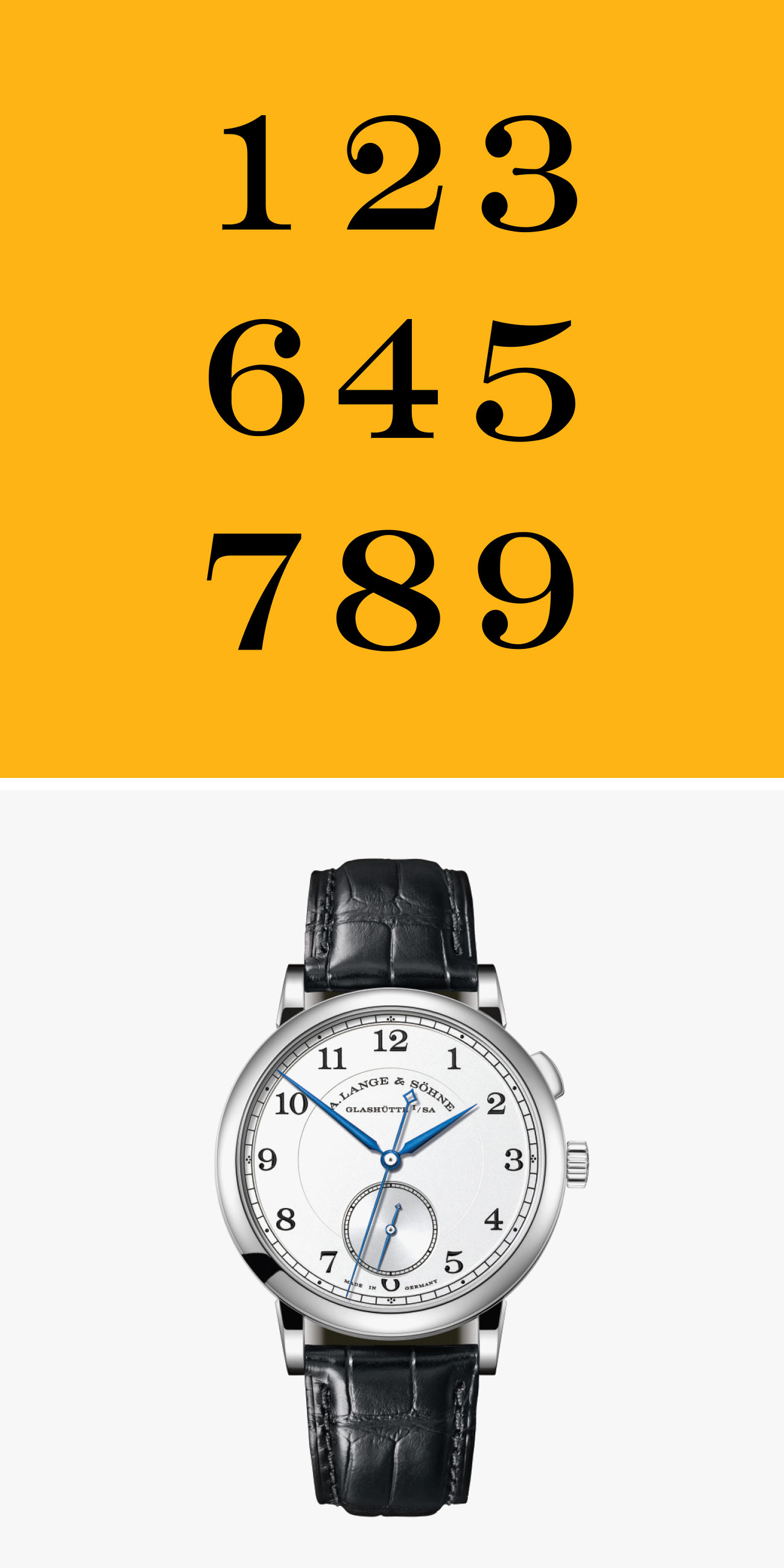

The Rolls Royce Phantom Oribe is a one-of-a-kind car for sure, combining two houses with more than three centuries’ combined experience and heritage between them, the Oribe combines ancient and modern into one car, it shows unique stitching and upholstery techniques for the luxurious interior, while hand painting techniques were required for the stunning exterior.

The bespoke Oribe Green shade for this specific car has been created specifically for this single unit, matching the characteristic green and cream glazes of antique Japanese Oribe ware, and Rolls Royce even allowed the customer to use their bespoke paint mixture to be applied to his private jet, even after it took several months for the specialists in the Surface Finish Centre at Goodwood to match the lustrous, deep-green glaze that characterizes these 16th-century ceramics.

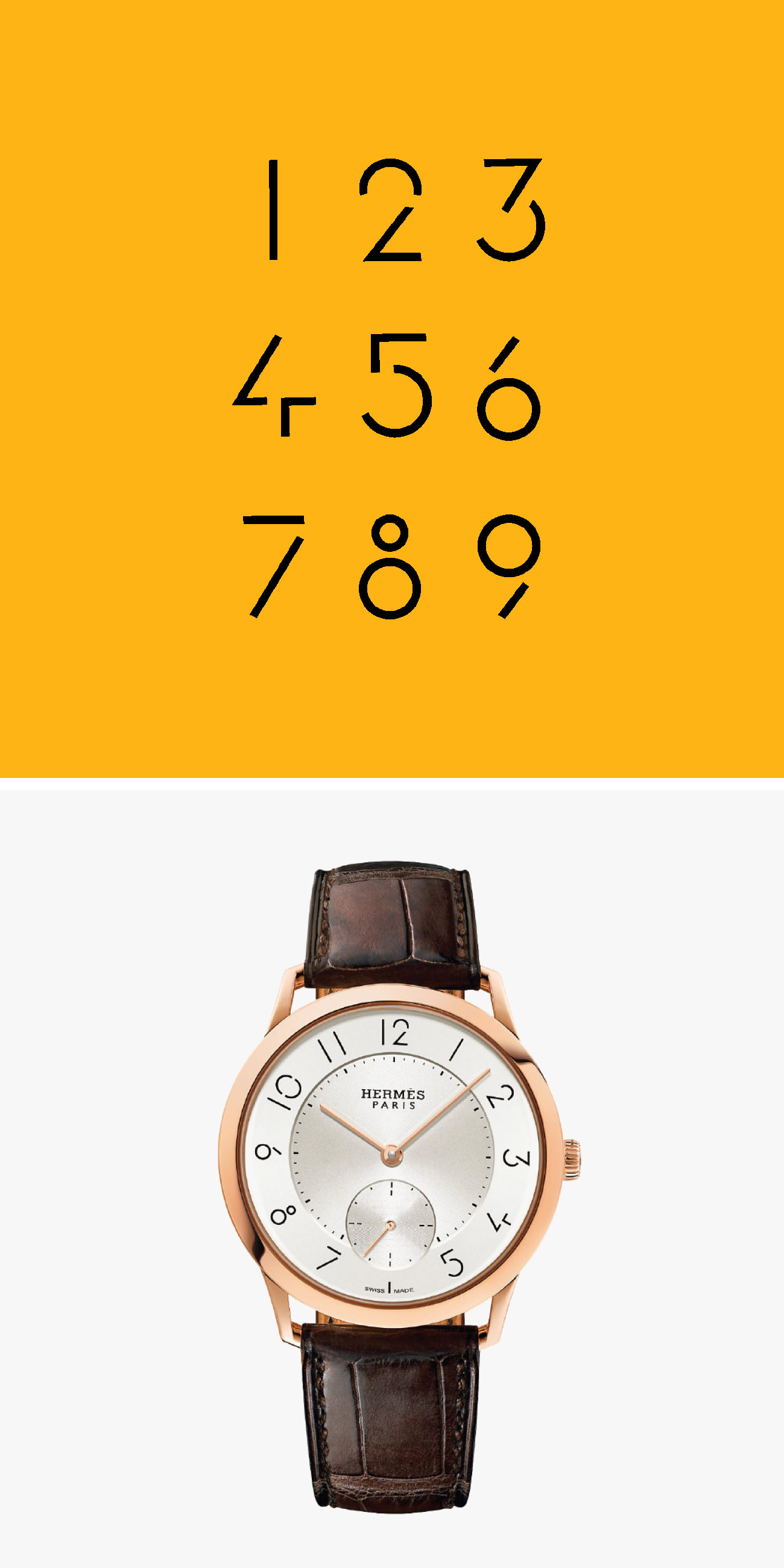

The Oribe style continues in the interior where it took Hermès designers and craftspeople in Paris, and the Rolls-Royce Bespoke Collective of designers, engineers, and craftspeople at Goodwood in West Sussex many months to create the individual components to showcase the tradition of both houses, mainly finished in Hermès Enea Green leather with Hermès piping on the headrest cushions and calf supports of the rear seats, while soft Seashell White accents and matching lambswool floor mats create a sense of light and space in this amazing interior.

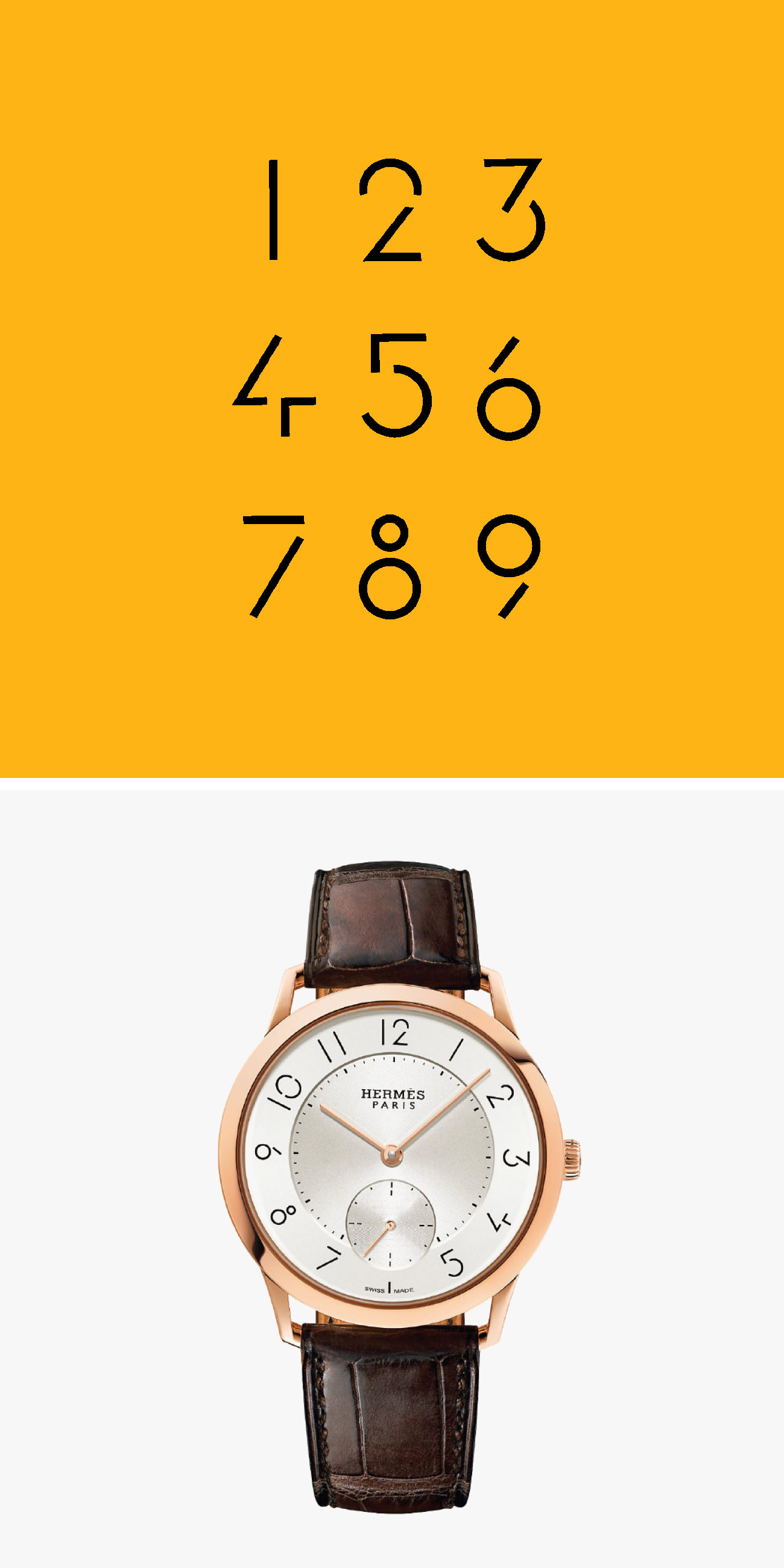

As this was a collaboration between Rolls Royce and Hermès, the glove compartment lid proudly shows an embossed with Habillé par Hermès Paris signature, while Wooden speaker frets, are formed by meticulously perforating the Open Pore Royal Walnut veneer applied to the doors, and to really stand out, Hermès ‘Toile H’ canvas is used on the door armrests, center, and rear consoles and, most notably, the signature headliner … a first for Rolls Royce.

Because this is a Hermès edition Phantom, the leather upholstery boasts stitching and edge-painting techniques originally employed by master saddlers, while the dashboard fascia on this specific Rolls Royce Phantom has been adorned by a special commission artwork based on a design by the celebrated French artist and illustrator Pierre Péron (1905–1988), inspired by the famous Hermès horse motif, is hand-painted on Open Pore Royal Walnut and is shown in true art gallery style … behind glass.

I guess it might be true what they say, you drive a Bentley, you are chauffeured in a Rolls Royce, so Mr. Yusaku Maezawa will probably be found in the rear seat of this truly amazing looking Phantom, in the utmost luxury and style, another unique masterpiece made in Goodwood, the UK.