A

ll around the boat, Lake El Salto was waking up. A purple glow seeped over the Sierra Madres, turning the lake’s surface into a puddle of ink. Tropical birds stirred along the bank, whooping like monkeys; high above them, an eagle circled with the regularity of a drone. In the little inlet where our boat was currently parked, fish the size of saucers — tilapia, gray with flamingo-pink-mottled bellies — flipped briefly out of the water and back in, like badly skipped stones, snatching at bugs no bigger than motes of dust.

Joe Thomas and Jim Kramer ignored all that. B-roll footage at best. Too much of that kind of thing, Kramer had quipped earlier, was for nature shows, not fishing ones. If there was a story to be told here, it was under the surface, hungry for breakfast.

Which is why their eyes, and the lens of Kramer’s camera, were locked on a small piece of plastic wriggling across the surface of the lake, its underside laden with treble hooks the size of a crooked finger. Thomas reeled in this “jitterbug” topwater bait using a long, sturdy fishing rod that could double in a pinch as a spear; the reel he cranked had a high-tech drag system that reminded me of a sport’s car’s disk brakes; his braided fishing line was all but impossible to break.

“Here, fishy fishy,” Kramer muttered. A bead of sweat ran into his eye. He didn’t flinch.

And then, like a stick of dynamite blowing up just beneath the surface, a Florida-strain largemouth, the mean mother of the largemouth world, engulfed the lure. Thomas arced his back, setting the hook with a yell. “Oh my gawsh!”

Kramer’s lens was trained on the fight. But then Thomas’s excitement flagged. The fish came easily to the surface, towed in toward the boat by Thomas’s fast reeling.

“It’s a small one,” Thomas said. Kramer lowered his camera rig and wiped his brow.

A small one? That was the biggest bass I’d ever seen. But I’d come here to watch Thomas and Kramer create their Outdoor Channel show, Stihl’s Reel in the Outdoors with Joe Thomas, and to try to understand what made their 30-minute fishing stories that fans watched from the couch work. And at El Salto, one of the world’s best bass fishing lakes, the story is something straight off the old treasure map: Here there be monsters.

Producer, editor and cameraman Jim Kramer is constantly behind host Joe Thomas as he fishes, stalking the scene with his surprisingly small Sony XD camera on a shoulder mount.

Thomas is square-jawed and thickly athletic. If you need a fish caught, he’s a good guy to have around. He competed on the professional bass fishing circuit for 30 years, making a good living fishing, and once won $1 million in a single tournament. In 10 seasons and with a relatively low budget, Thomas’s show has taken anglers to untouched blackwater lagoons in the Amazon, man-made lakes in the flyover states loaded with largemouth bass, and deep sea fishing in the Florida Keys.

“I was at the right place at the right time,” Thomas said. But it was more than that. He wrote a book called Diary of a Bass Pro in 1996 that was made into a television show, Angler on Tour, combining bass fishing and reality TV just as both waves were crashing into the public consciousness. On a boat and in front of a camera, he’s a normal, level-headed guy from Ohio who also happens to have a flair for funny, goofy ebullience without coming off disingenuous. On the boat that morning at lake El Salto, Thomas told me his three keys to a great fishing show: a) be entertaining; b) choose locations that are unique and have great fishing; and c) teach the viewer something. I got the sense that he understood entertainment just as much as he did the whims of a largemouth bass.

“Here, fishy fishy,” Kramer muttered. A bead of sweat ran into his eye. He didn’t flinch.

The other half of the show, Jim Kramer, is a city slicker turned outdoorsman, thanks to the fate of the job market. He and Thomas are partners in showrunning; Kramer handles camerawork, direction, production and editing. “I try to approach it in a documentary, or almost cinema verite style,” he said. “Look, let’s see what happens. Flexibility is a good thing, especially when you’re depending on a creature with a brain the size of a peanut.”

Much of Kramer’s work is behind the scenes, but on the lake, he is constantly behind Thomas as he fishes, stalking the scene with his surprisingly small Sony XD camera on a shoulder mount. It’s tough work: physically exhausting, mentally intense, and requiring a keen eye for the bigger picture amid what is in equal parts chaotic and boring.

“Originally, fishing shows had a very passive type of filmmaking,” Kramer said. The cameraperson was almost always in a second boat, taking in the whole scene of fishing, using a zoom when necessary. “What I want to do is get close. I’m trying to look at it as a person who’d be viewing it as a fishing partner.”

“Bass fishing has so many variables and options,” Thomas said. Based on types of water and season, the techniques are endless. You just keep learning.”

I remembered that “passive” camerawork from my childhood. On Saturdays, while other fathers and sons geared up for college football, me and my dad tuned into early morning sessions of ESPN2: 23-minute segments of overly tanned men, dressed in lightweight button-down shirts and baseball caps, standing in the bows of small, high-tech motor boats, fishing.

We exulted in grainy footage of Jimmy Houston, his bright blonde bowl cut not yet adopted as the go-to styling of Hollywood’s young manic pixie dreamgirls, drawling away and kissing the bass he caught on the lips before releasing them. Jose Wejebe, the zen master and happy hippie behind The Spanish Fly, chased enormous saltwater monsters with his fly rod. Bill Dance staged slips and falls, his guest hosts guffawing till they looked like they’d keel over.

But ESPN eventually canned their outdoors coverage, replacing it with all manner of mainstream-sports talking heads. The fishing show, of course, was not gone. Its sort of entertainment, both vapid in its appeal to fishermen (guys catching fish!) and touching somewhere deep inside their souls (guys exploring every emotional and cerebral aspect of the fishing life that I adore!), simply moved to greener pastures: dedicated mediums like the Outdoor Channel, now beamed into 42 million homes throughout the US, its every aspect tailored to the outdoor life. No need to try to hook the football crowd when you’ve narrowed your audience to just guys who know what the word “tippet” means.

Yet while the forum for sharing the fishing show has honed in, the appeal of fishing itself has broadened. Last year, 45 to 50 million fishing licenses were sold in the US, making it one of the top leisure time activities in the country. Those changing demographics are reflected on Stihl’s Reel in the Outdoors. “There has always been a stereotype of some good old boys in a leaky johnboat, putting back some PBRs and catching some fish. But any more, that’s not the case,” Kramer said.

On their show, the framework centers on Thomas catching monster fish, which he does almost every episode. But the excitement comes more from Thomas himself, and his guests, whom Thomas clowns with and gets to know intimately in equal parts. There is adventure and excitement beyond just casting: In Florida, Thomas was almost thrown overboard by a huge goliath grouper; in the Amazon, he and Kramer spent hours (in the show, a few minutes) trying to navigate mangrove swamps and find an untouched fishing hole that felt more sacred than secret.

Thomas and Kramer make their money differently than other shows, too. Their main sponsors are mostly “non-endemics” that are not directly tied to fishing, like Stihl. “A lot of outdoor shows are highly commercial,” Kramer said. “I get it, but the old joke we used to tell is that when a guy gets one, it’s “Aw, get out from under that Ranger bass boat! Oh, he’s in my Evinrude outboard. Oh man, he’s got my Trilene line tangled up in my Motorguide trolling motor!”

Juan, 30, makes his living as a guide on Lake El Salto. The Mexican government flooded the valley when he was just a child to create a lake for farming tilapia; when I asked him where he grew up, he pointed to the water about 50 yards from where we were casting.

The magic of the fishing show, though, remains obscure. “We still have people who approach us and say, how do you catch all those fish in a half an hour?” Kramer said. “They’re not really aware of what goes on behind the scenes.”

The more time I spent among Joe Thomas’s biggest fans at Lake El Salto, the more I understood how such ignorance was possible. Why should the audience care what kind of cameras Kramer used, or how Thomas and Kramer mapped out their story lines and edit points? It was just like the rest of the entertainment world: it’s all about creating a good story and staying the hell out of the way.

Bass fishing is, Thomas said, the perfect sport for building an avid membership. “Bass are everywhere. You can catch bass in every state in the US except Alaska. That gives everybody an opportunity to catch them, whether that’s in a tiny farm pond or a huge river. You have variables and options. Based on types of water and season, the techniques are endless. You just keep learning.”

Fishing, like all great sports, can sink its hooks in deep. It’s as addicting as good drugs, as mesmerizing as good philosophy. It helps to remember that the greatest American novel, Moby Dick, is really just a fishing story in which the fisherman becomes so obsessed he goes mad. (Happens all the time.)

At El Salto, my first brush with the cult of bass fishing — and Joe Thomas fans — was the gang of fishermen staying at the Angler’s Inn fishing lodge along with the show’s crew. They were twanging with excitement. They were young and middle-aged and old. They were oil derrickmen and engineers and bankers. (There was one woman, a wife who had become as obsessed with bass fishing as her husband.) And they were utterly, bitterly, ass-clenchingly obsessed.

Take Bruce. Bruce was from Ohio, about 65 years old, big bifocal glasses, friendly, midwestern twang. When he fished during the day, he wore a red bass fisherman’s jersey emblazoned with sponsors.

“I first heard of Joe Thomas about 25 years ago,” he told me. “He was a local guy from Ohio, and I’m a local guy from Ohio. And so I started rooting for him in the pro circuit. He makes the great fishing he does easy to understand for dummies like me.”

I try to approach it in a documentary, or almost cinema verite style,” Kramer said. “Look, let’s see what happens. Flexibility is a good thing, especially when you’re depending on a creature with a brain the size of a peanut.”

Bruce met Thomas, who invited him to fish with his crew in El Salto. “But back then I was a family man and I didn’t have the money,” Bruce said. (Three and a half days of fishing at the Angler’s Inn, the best lodge on the lake, including food, drink, and guiding services included, costs $1,650, plus airfare.) Years later, Bruce was retired and his kids were out of the house. He met Thomas again at a local event, and Joe invited him to go fishing in Mexico. “My wife told me to go. So we saved up for a few months, and now I’m here,” he said.

Earlier that day, Bruce had caught his personal record bass. When he told me about it, I thought he might cry, he was so happy.

The bass fishing at lake El Salto has been life-altering for an entire region. The lake is actually a dammed up river that flooded a huge range of valleys, drowning everything in its way but people. Today the dead trees still litter the edge of the shoreline, their limbs reaching eerily out of the shallows.

While fishing with Thomas and Kramer, I asked our guide, Juan, 30, where he grew up. He pointed to the water about 50 yards from where we were casting.

When the Mexican government flooded the valley that is now El Salto Lake, they displaced about two villages and several graveyards. Juan said this was not a bad case of eviction: most villagers went happily, with money and supplies to build much bigger homes in the villages on higher ground 10 minutes from here. He was three when his family moved. He has one memory of his original home: being bitten by his aunt’s dog.

Today his family’s home is one of his secret spots to fish on the lake. Not bittersweet to him at all. It’s great fishing, not to mention his livelihood.

At night, all the lodge’s guests sat under the lodge’s open-air cabana, breathing in the sultry air, shooting the shit, sharing stories. Earlier in the day a storm had rolled over the Sierra Madres and exploded over the lake, dropping bolts of lightning every minute or so. All the guides and guests had fled back to the lodge, except for one boat. An older man and his son had stayed out. Now he unspooled what it was like hunkering down in the deluge, convincing the guide to stay out. He and his son had caught two monsters, one of them a ten-pounder, the ultimate prize of El Salto. He had felt so alive, out there, in danger, fighting the biggest bass of his life, he said.

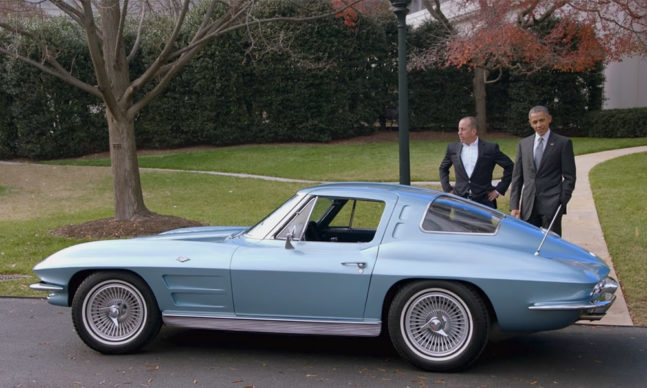

A man, buzzcut and ink suggesting a biker vibe, who had stayed quiet most of the trip spoke up from the back. He understood the feeling, he said. He told a story while everyone sat still and deadly silent under the cabana.

About five years ago he had to go get a cholesterol check. His doctor asked him when he’d gotten his last physical. It had been 25 years, so the doctor demanded he give the man one. What he found was not good.

An emergency surgery followed, followed by many other surgeries, followed by a diagnosis that the man was going to die.

The man did not take the news well. Even though he had two kids and a wife, he found that nothing could keep him happy — that doctor’s voice kept ringing in his ears when he was with the people he loved, or doing the things that used to make him happy. You’re going to die, soon, he heard. What could life mean when this was where we were all headed?

The man had always wanted to get a tattoo, so he did. During the four hours it took, the pain did something nothing else had been able to do. It took his mind off of death.

He started getting more tattoos.

The tattoos helped. But six months, then a year, went on, and he had more surgeries, more bad diagnoses. There was not enough ink in the world, he realized, that could keep him going. He started planning his suicide. He told no one, but he made sure his kids would be taken care of, and he started saying goodbyes, subtly, to his friends and family.

“The secret is,” Kramer said, “Joe still really likes this. He’s having fun. The best stuff that we get is when the fishing’s really good. And he and his guests are having a good time. And they forget the camera is there.”

He went to see his nephew, who had MS — bad — but was close to graduating high school. The nephew told the man he was his hero. Because he had survived his disease and kept on fighting, the nephew knew he could survive, too.

The man did not kill himself.

He got one more tattoo, of his nephew’s portrait, on his side. Under the cabana, he pulled up his shirt to show it to everyone. Underneath it, I read the words “My strength and my courage.”

“When I ran out of space to get tattoos, and I still needed therapy to keep my mind off death,” the man said, “I started bass fishing.”

“At the end of the day,” Jim Kramer told me later, “I want a guy to be able to turn on our show, crack open a beer, and forget about the bills he has to pay or the transmission that has to be fixed. I want him to be able to take thirty minutes off and enjoy life.” That, he said, is what fishing is all about.

“People come up to me and tell me they like my show because I act normal,” Thomas told me. “They say, ‘We see you feeling bad after messing up and losing a big fish, and then when we mess up and lose a big fish, we don’t feel as bad.’” Could it be that fishing is so big that all Joe Thomas and Jim Kramer have to accomplish is being themselves and catching fish for 23 minutes? They make that look easy, sure. But could the secret to a good fishing show be so simple as the fact that fishing inherently brings its own implications about life, death and happiness to the equation?

One day, as we watched Thomas casting again and again to the same spot, Kramer told me Thomas’s secret: “He still really likes this. He’s having fun. The best stuff that we get is when the fishing’s really good. And he and his guests are having a good time. And they forget the camera is there.”

On the last full day at El Salto, Thomas and Kramer were hustling to finish their footage for the show, and the fishing was tough all of a sudden. Juan and I, casting occasionally from our boat nearby, had caught two small ones near his old home. From what I could tell, Thomas had caught only jack and shit.

Juan lifted his big crank bait out of the water and handed me a beer. “See that cross up there?” He said. I had seen it — a big white stone cross atop an island hill, in sight of the lodge. I’d figured it was something along the lines of the Virgin Mary shrine that sits atop the high cliff in the middle of the lake, where someone had said once a year men gather with 20 cases of beer to shoot off their submachine guns.

“At the end of the day,” Kramer told me later, when we’re out on the water, fishing alone, “I want a guy to be able to turn on our show, crack open a beer, and forget about the bills he has to pay or the transmission that has to be fixed. I want him to be able to take thirty minutes off and enjoy life.”

“It’s for a fisherman here, nicknamed El Tigre.” An American, he said, who’d loved the lake so much he’d requested his ashes be spread in its waters. The lodge had paid for the monument.

Five minutes later Juan had beached the boat and I’d climbed the hill, skipping from rock to rock in my crappy boat shoes, keeping an eye out for rattlers I was sure would be sunning themselves in the evening sun. At the crest of the hill I found the cross, the inscription facing the lodge and the Sierra Madres beyond. It read “August Tigre Hansch. At Peace in El Salto. 9/16/1920 – 7/23/1997.” Below the name was a fishing lure, a crank bait, embedded half into the rock like an ancient fossil.

I poured out a sip of my Pacifico for anglers that’ve gotten away. I heard a big splash and a joyous hoot down below, and scrabbled over the lee of the hill, into view of the swath of the lake, flashing its silver against the all-knowing mountains beyond. Joe Thomas and his boat were down there. Joe’s rod was bent in half. The camera was trained on him, and he was fighting a big bass.

Bass Fishing, America’s Biggest New Collegiate Sport

Bass fishing, along with lacrosse and volleyball, is one of the fastest-growing collegiate club sports in the country. We found out why. Read the Story