This Company’s Pilots and Dive Watches Are Made for Professionals

“We haven’t tried to appeal to everyone — we’ve said this is who we are, and we’re going to keep that style. And we’re not designing by committee. It’s about a classic-style aviation watch.”

Sounds like a pretty straightforward sentiment and mission statement, if you ask us. Giles English, who along with his brother Nick founded Bremont in 2002, is under no illusions as to what his company is and is not. When the two brothers decided to establish their watch brand following the death of their father in an aviation accident, they had a very particular goal in mind: namely, to bring watchmaking back to the UK. And they decided that if they were going to embark on that mission, that they were going to do it correctly, and without cutting any corners.

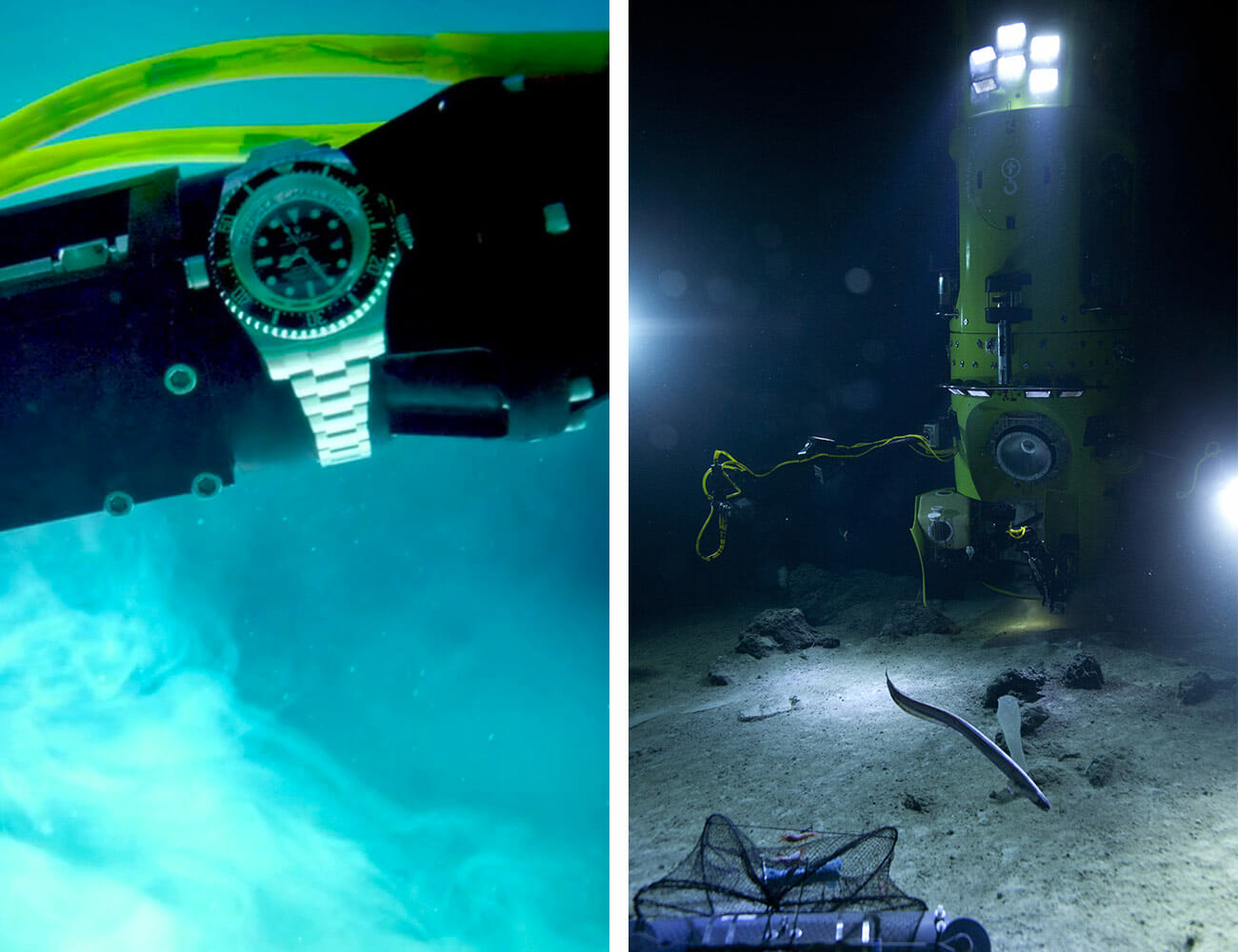

It took a full five years until the first Bremont watches were ready for delivery, in 2007. Since then, it’s been a whirlwind adventure making watches for various militaries; for the civilian market; and in collaboration with some of the most iconic British brands, personalities and products of all time, including Jaguar, Martin Baker, the Concorde, and more. If you’re a real-life adventurer, soldier, racer or sailor (and especially if you happen to be English), there’s a very good chance that you rock a Bremont watch as your daily wearer.

17 years after Bremont was established, the company employs roughly 30 watchmakers and about 160 total employees, and turns out roughly 10,000 watches per year. But the challenge is hardly over, though the initial growing pains may be behind them: “Everyone said we were mad, and we knew we were a bit mad,” says Giles. “And it’s been very hard — there isn’t a single day when it’s been easy. But it’s been very exciting and we’ve done something not a lot of people have been able to do.”

Amen to that.

We visited Bremont’s facilities in Henley-on-Thames, about an hour outside London, to get a better sense of what their operations are like, and how they design and manufacture their watches. Though the company is currently building a brand new, state-of-the-art facility from the ground-up, Bremont currently relies on several smaller facilities, which it’s quickly outgrowing. Stay tuned for more coverage next year when their new manufacture finally opens, but more now, scroll down for a view into how Bremont’s bringing watchmaking back to England.

Photo Tour

A vertical mill is used to manufacture flat movement components, such as baseplates. While these machines are sufficient for small numbers of components, Giles explains the need for more advanced machines with higher spindle speeds that can churn out, say, a baseplate, in less than an hour (it currently takes about five hours to machine a single one now, given the surface’s complex geometry).

Special plates are used that are perfectly flat, which are then machined, deburred, put through a polisher, and have perlage (decoration) added to them, after which they’re sent to be plated. Bremont, like many other manufacturers, doesn’t do plating itself, which is a skill best entrusted to someone who a shop that specializes in it. Bremont does, however, manufacture all its own jigs itself.

Finding competent watch assemblers in the UK is no easy task — you can’t simply go out and recruit dedicated, established workers with a long history in the industry. Giles English explains: “If we want a watch assembler, we have to go out and get 50 people for bench tests — do they have dexterity? These guys have never dealt with watches before, they’ve come from all different backgrounds. There’s no watch industry (here in the UK) to choose from, so we have to take people from different industries.”

“They may have never seen a watch before, but do they have the dexterity to start off with, and do they have the mental mindset to do this for hours and hours — you whittle those down pretty quickly, and then it’s a long time training process to be able to do it. If you went into any other large Swiss workshop of ours size, it would all be assembly line production — for example, one guy just puts the crowns on. We do a tiny bit of that, but not really so much, and the reason why is we’re training future watchmakers who can then go onto different parts of the business. So we’re trying to build as much of that skillset as possible.”

“We haven’t tried to appeal to everyone — we’ve said this is who we are, and we’re going to keep that style. And we’re not designing by committee. It’s about a classic-style aviation watch.”

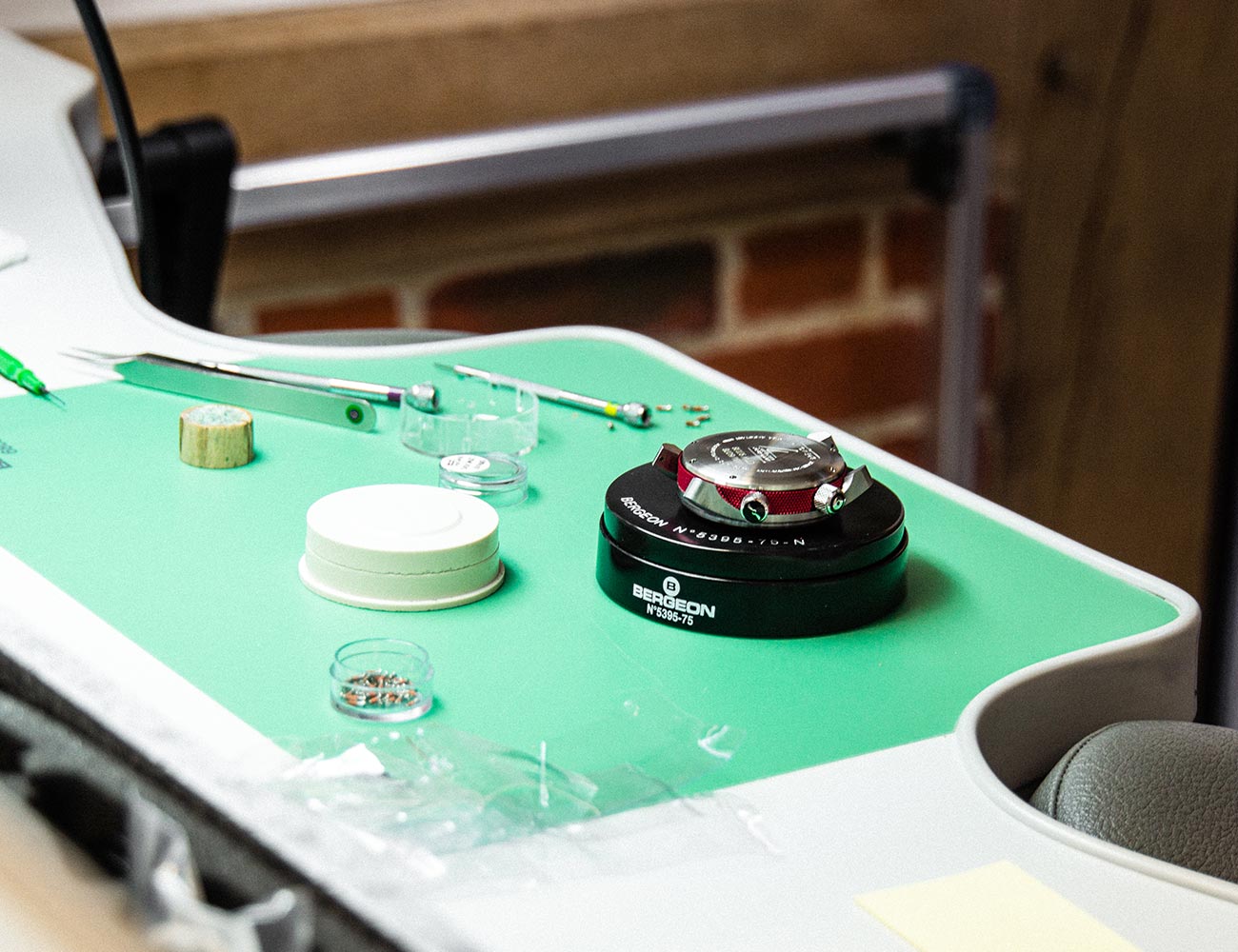

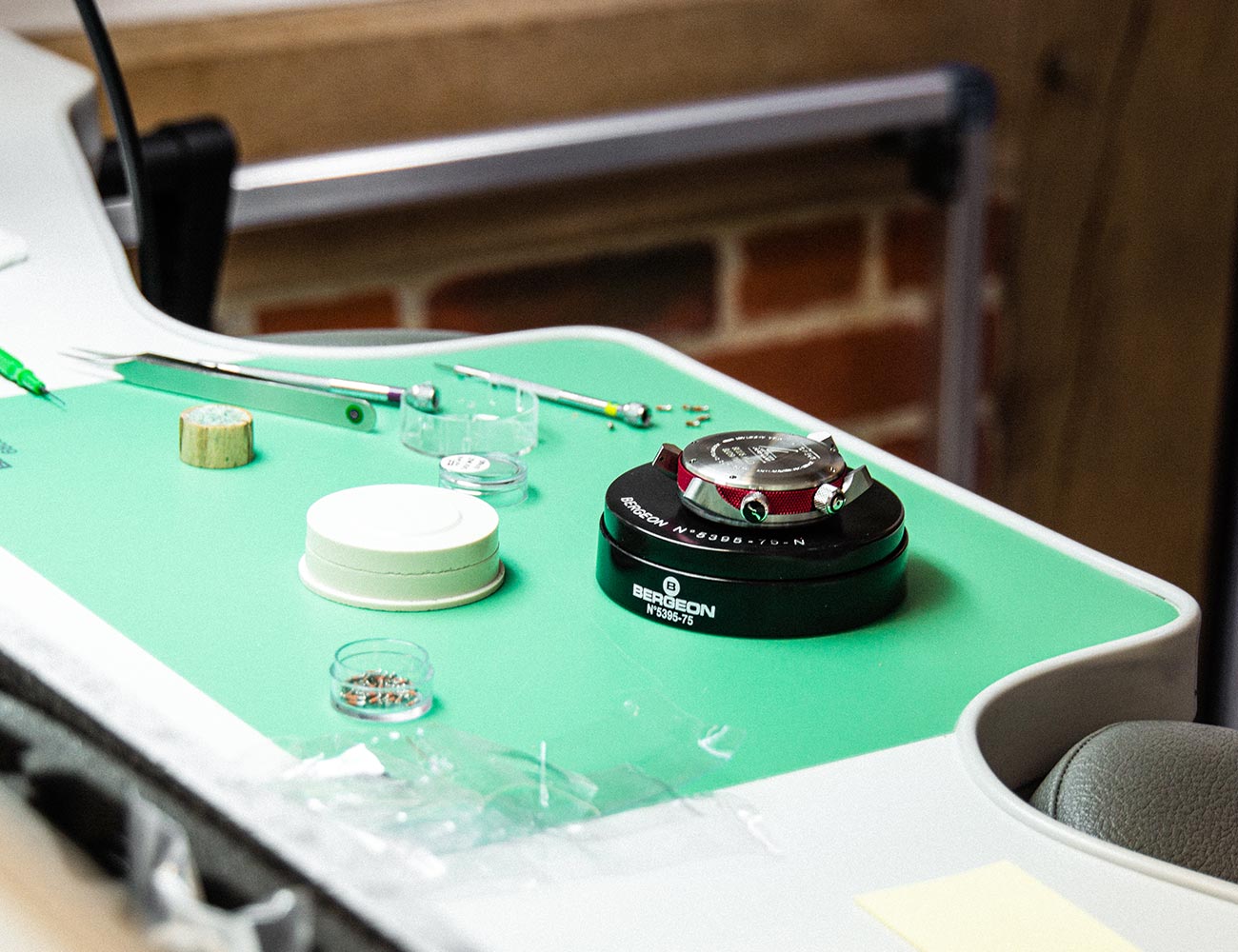

Stu, Bremont’s first watchmaker, works on a Codebreaker, a special edition watch from 2013 that utilized wood from Bletchley Park floor boards and metal from an original Enigma machine, the famed Allied codebreaking machine from Work War II (Bletchley Park housed the famed codebreaking facilities). The Codebreaker is a complicated watch, featuring a flyback chronograph as well as a GMT complication.

Standard screws used to affix rotors to automatic movements are normally blued and utilize a normal screw head, but the weight of a rotor spinning puts a large stress on them, so Bremont designed their own screws. The Bremont screw head has two small holes in it and utilizes a screwdriver tip with two small “dots” that grip the head. This system increases the tensile strength of the screw considerably, and the screws don’t need to be blued, which weakens them. The new screw design solves the problem of the screws shearing in half because of the stress of the rotor spinning.

Of course manufacturing ones own tools is costly — the screwdriver grip that Bremont’s watchmakers use is standard, but the bits are custom-made to the tune of 600GBP per unit. “Every seal, every screw is all bespoke to us,” says Giles. “So a lot of brands will buy generic components off the shelf. We do it all ourselves, which means we have control over what is being made.”

“We don’t want the watchmaker to be filing parts to get the case together. If we were building 100 watches a year, we could do that — you can have slightly substandard stuff. But our stuff has to be perfect.”

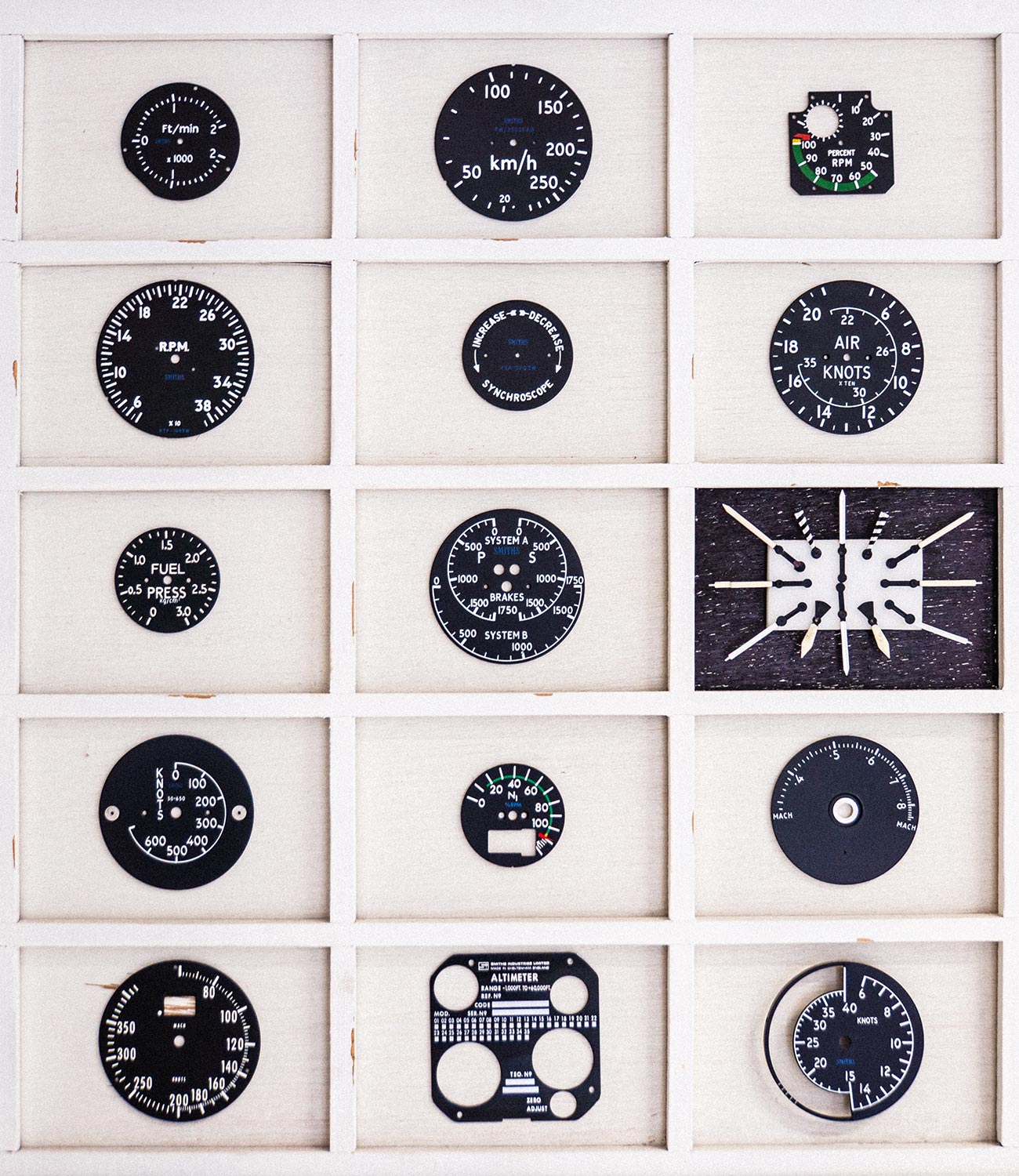

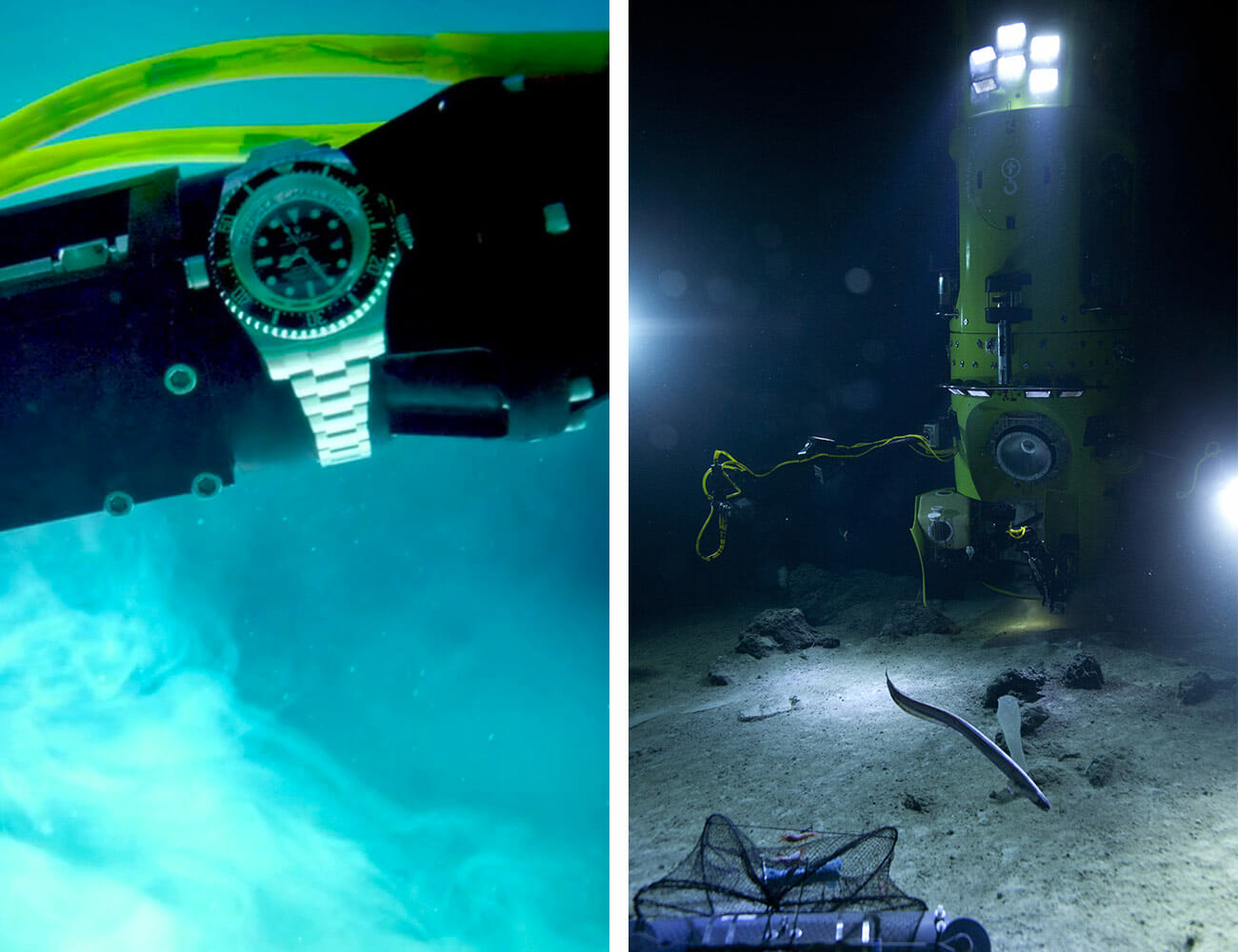

Nick and Giles do all the design work themselves, mostly by mining the troves of aeronautical instruments that have come before: “We haven’t tried to appeal to everyone — we’ve said this is who we are, and we’re going to keep that style. And we’re not designing by committee. It’s about a classic-style aviation watch. An aviation watch is not a dive watch and not a dress watch — it’s that middle ground and category.

Before we came along most of the aviation watches were so delicate that you couldn’t wear them while flying — they were becoming dress watches. Whereas we wanted something that was tough, easy to read and that you’re able to wear in the boardroom or up Mt. Everest. That was our whole remit, which is why we started getting adventurers and explorers and those guys to start wearing our watches.”

Bremont builds most of its watches using their proprietary Trip-Tick three-piece case (the Her Majesty’s Armed Forces collection being a notable example). Because the company’s cases are specially hardened, they can’t be polished during service, but rather replaced entirely. However, because the cases are built in three pieces, they can simply replace, for example, the bezel component without having to chuck the entire case. (This was part of the original thought process when developing the three-piece case). The steel used by Bremont is 7-8x harder than that used in the average watch case.

A five-stage process is used for case manufacturing, and between each stage, the case must be polished and satined (after the final plating stage, which is done by a specialist company, the cases can no longer be polished). The final polishing stage is done by hand by a skilled employee, and between each of these stages, the cases must be cleaned and kept in small silk bags for protection. Over-polishing can ruin tolerances and prevent parts from fitting together, such as a crystal onto a case.

“If a watch gets tested for three weeks and comes back and there’s even a speck of dust, the entire watch needs to be rebuilt. So it’s all about quality control.”

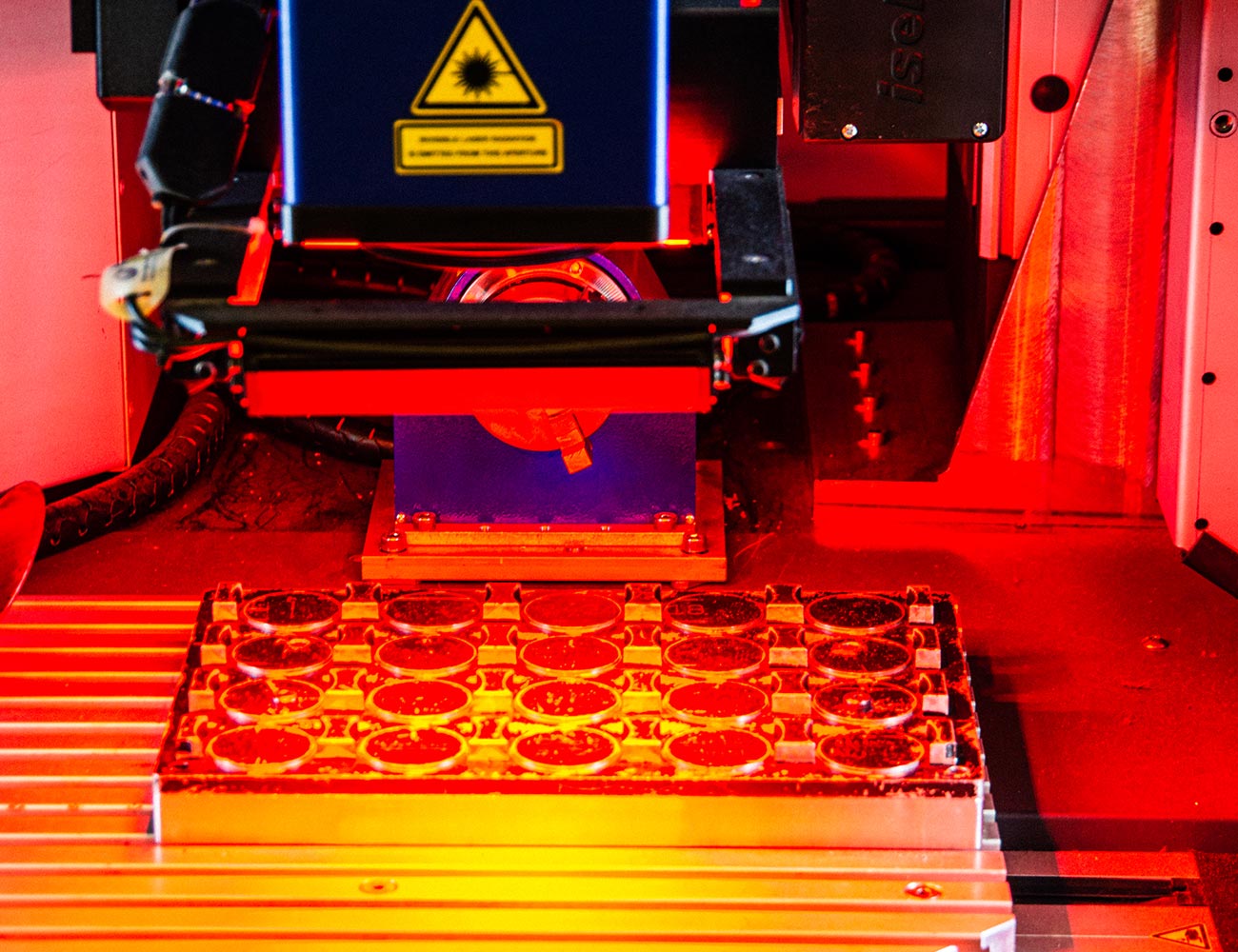

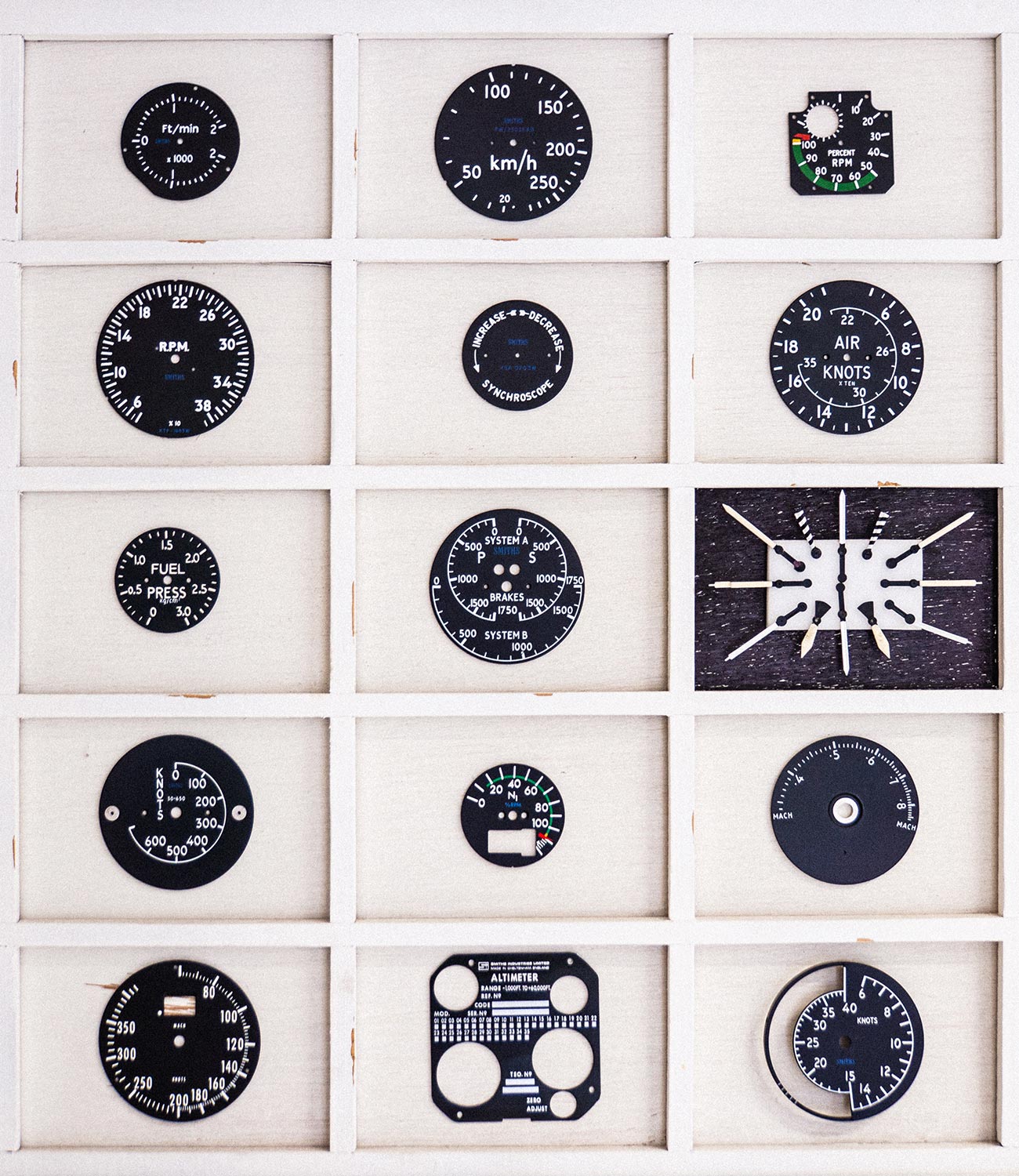

A laser is used to engrave the sequential numbering that appears on case backs, as well as lettering, such as the company wordmark (the lasers used by Bremont are powerful enough to cut straight through steel) — etching, however, is outsourced. Bremont has become so adept at using their laser engraving machines that the manufacturer even contacted them, asking how they achieve certain techniques.

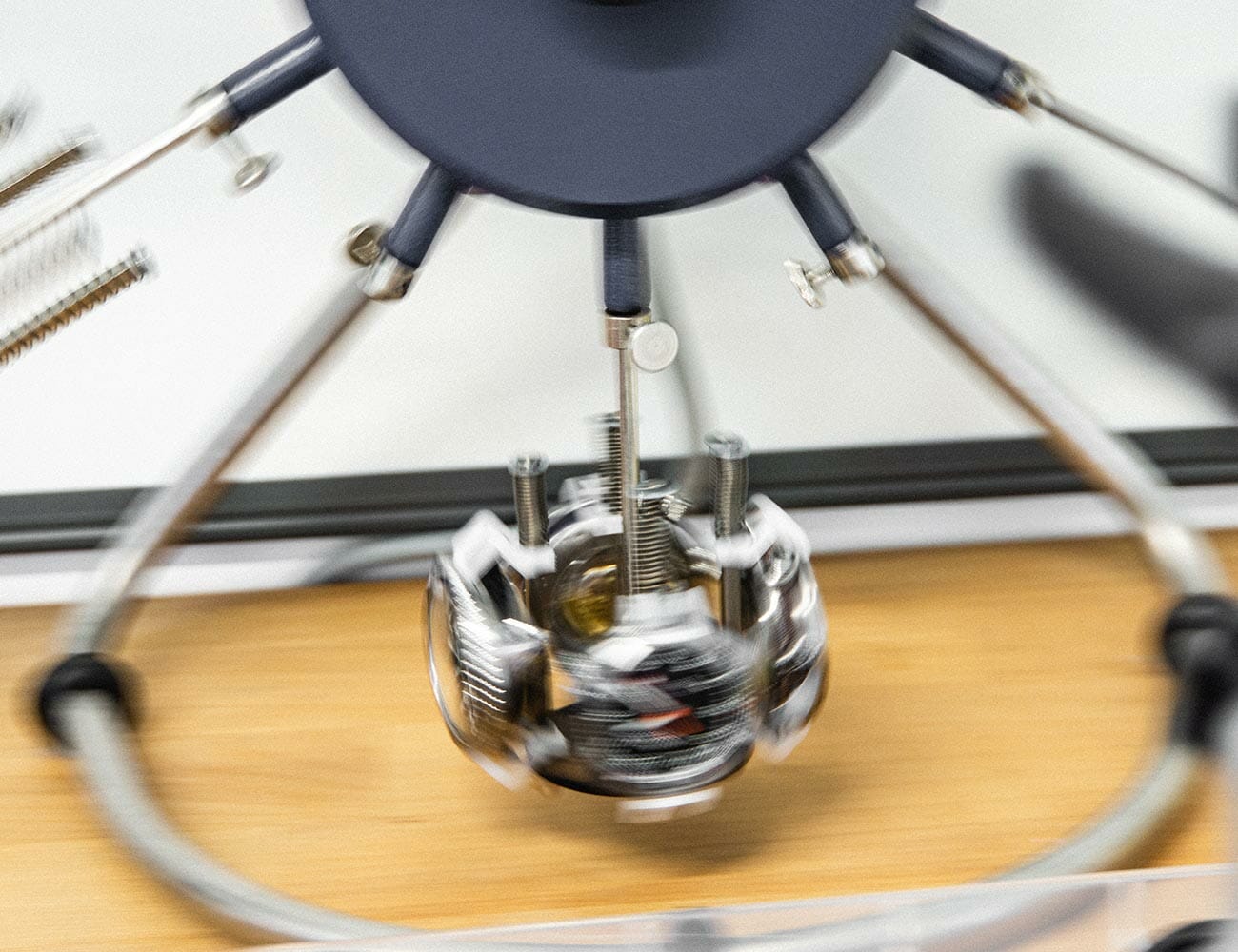

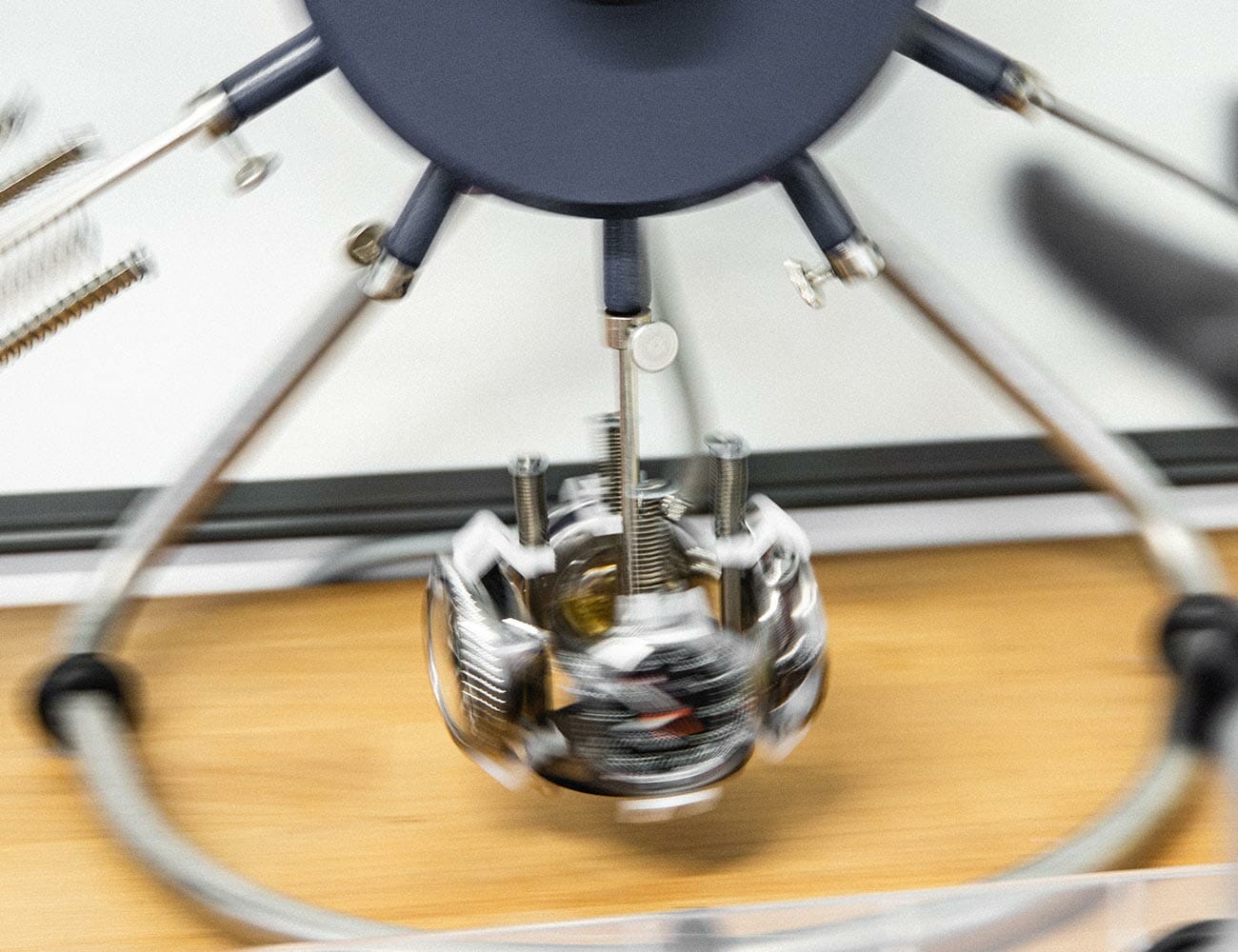

Once Bremont receives a COSC-certified movement from Switzerland, it’s already been tested to rigorous standards — but tests are conducted on the movement only, not on a watch containing it. “So what we’re doing is regularly testing them the whole time,” explains Giles. “We have systems for batch-testing in five different angles — our watches should be +/- 3 seconds per day. When the watchmaker then does his own individual QC and feels that it’s perfect, then the watch will go upstairs to be individually QC’d.

With watchmaking, it’s all about first-time pass rate, meaning, can I work quickly enough so that I can build my quota without making any mistakes. Because if that watch gets tested for 3 weeks and comes back and there’s even a speck of dust, the entire watch needs to be rebuilt. Our machines will batch-test and keep digital records for us, so we can track when it was tested, what tests were run, sort of like block-chain.”

Kits of watch components are put together on the upper floors of Bremont’s Henley facility, after which they make their way downstairs for assembly. These components have been thoroughly QC’d and may have been sitting for some time in stock. “The idea is to deliver a perfect set of components devoid of scratches, defects, etc. to the watchmaker,” explains Giles. “When it comes to the watchmaker, they want the watch to ‘slide together.’ We don’t want the watchmaker to be filing parts to get the case together.

If we were building 100 watches a year, we could do that. You can have slightly substandard stuff. But this stuff has to be perfect. We want them to be pure assemblers. And that’s the hardest bit and has taken years, to get good-quality components throughout the business. If a component is off by even a few microns, it can throw off the entire process.”

Each watchmaker at Bremont has his or her own custom-built desk, assembled to that watchmaker’s height. Each watch is largely assembled by one watchmaker, who will be given kits of components from the upper floors at Henley. Rather than work on one watch a a time, this person will line up several watches, affix their dials, hands and crowns, and build them. This way, as Giles notes, there is some efficiency to the process. Each watch is numbered and has an individual movement and case number. Each watchmaker has their own tools and when they leave, they leave their desk clean. They also learn how to sharpen their own tools and look after them.

“When you first learn you work on standard 3-hander watches,” says Giles. “When you’re working with chronographs and GMTs you have all different hand heights and if you put these on incorrectly, they can rub against the crystal, cause problems, etc. You train to get to complicated watches.”

Sometimes the simplest solution is the best one. This machine is filled with ceramic beads that vibrates subtly and remove burrs from case components after roughly ten minutes. But the machine has to be watched very carefully — too much time will ruin the components, and not enough time will have a negligible effect.

While all watches go through highly rigorous testing at Bremont, it’s perhaps the military watch projects that mean most to the English brothers. “What we love, the most satisfying part of the business is making for the military all around the world, for lots of different nations, begins Giles. “And a big part of it is that if they’re buying en-masse, they’re getting a deal, they’re effectively subsidizing it. There was a guy, an F-18 pilot who said to me look, I’m flying an F-18 for seven years of my life, but I’ll spend the rest of my life talking about it, and the watch is proof that I did it. I’ll give it to my son, and he’ll tell his son that his grandfather was an F-18 pilot. It becomes a complete badge of honor for these guys. And there’s not much you can buy that does last forever.”