The challenges facing the International Watch Company as its 150th anniversary loomed were actually good ones to have — namely, how to expand IWC’s business and bring all its manufacturing and assembly together under one roof, and all this whilst honoring the company’s past and anticipating its future. Thankfully, when your CEO is a trained architect, these challenges are made much simpler.

To meet these challenges in time for the company’s 150th anniversary, IWC has opened a brand-new, 13,500-square meter facility just outside the city center of Schaffhausen, Switzerland, the brand’s long-time home base. The new Manufakturzentrum, which was completed in just 21 months to the tune of 42 million CHF, is a glistening masterpiece of both modern and classic design that manages to incorporate disparate architectural cues into one cohesive building.

We traveled to Schaffhausen to tour the new center for ourselves, but as is often said, a picture is worth a thousand words…

The new Manufakturzentrum sits on the outskirts of Schaffhausen, in a quiet meadow with open green spaces all around. A German architectural firm had the idea to design the 139 x 62-meter building such that it would integrate into the sloping terrain, after which IWC CEO and architect Christoph Grainger-Herr then developed the initial design concepts for the external facade.

Grainger-Herr sought inspiration from disparate sources when designing the new Manufakturzentrum’s facade, including from both residential architecture and modernist exhibition pavilions. “The modernist export pavilions were all about showcasing the nation’s best inventions, best engineering, best art, and us being at this borderline between art and technology, this kind of half-lab, half-artist’s studios, seems like an interesting way of expressing the brand.”

“In terms of what the building should represent from the outside, I was looking for an expression that’s much more luxurious and much more residential in a sense,” says Grainger-Herr. “We were able to say okay, let’s take these more residential materials all around the visitor path, and then make a transition into something very technical, white and almost lab-like to show the delicacy of the products as well, the R&D-sort of content of what we’re doing, which felt to me like the appropriate expression.”

The lobby and welcome area is an airy, 9 meter-high mass of steel, glass, marble, and wood, with a view of a forest just across the road. “What I think we can always hope to do is to take people onto a journey that really takes them from the environment and lifts them into something else where they can experience…a dream world, because it’s an emotional product,” says Grainger-Herr.

One of the walls in the Manufakturzentrum’s lobby is adorned with portraits of IWC directors and long-time personnel, including the brand’s founder, American visionary Florentine Aristo Jones (far left). Jones came to Schaffhausen in 1868 and established a company by the banks of the River Rhine that paired traditional watchmaking with advanced production techniques and engineering. The first four directors together presided over 100 years of IWC watchmaking.

“The modernist export pavilions were all about showcasing the nation’s best inventions, best engineering, best art, and us being at this borderline between art and technology, this kind of half-lab, half-artist’s studios, seems like an interesting way of expressing the brand.”

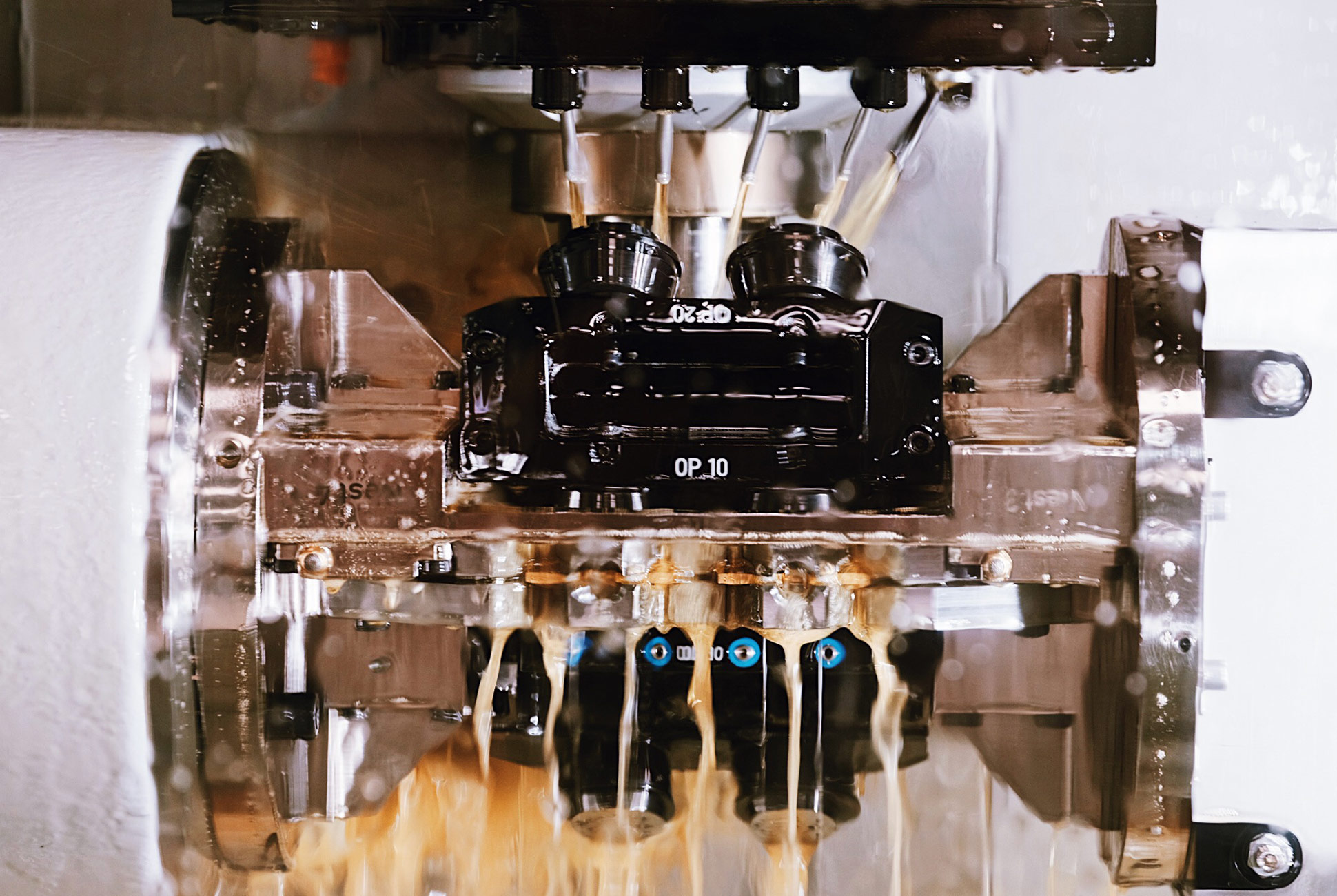

Seen here are examples of raw materials used in the production of movement components. The materials, such as brass and steel, come in long rods, which are suspended in oil in a machine and then cut into smaller sizes, after which they are punched, cut, polished and finished as necessary. The professionals cutting these pieces are called “polymechanics”, and are required to do four years of apprenticeship before beginning work.

Over 1500 components are produced in the movement-component production area, including parts so small that they are invisible to the naked eye. Says Grainger-Herr: “You come from the narrow streets of the old town, and then it opens up and you have this 9-meter lobby, and from there you go into small parts — from really wide to thousandths of a millimeter. This whole idea of expanding and then narrowing down again is a subtle psychological thing.”

Machines are programmed to produce only one type of part at a time, and two production methods are used: one via contact-less electric discharge, and one via a milling process. While certain older types of machines are only capable of working one side of a brass plate at a time, more sophisticated modern models can flip a plate over in order to work both sides, which allows IWC to run the machine over weekends, 24 hours a day.

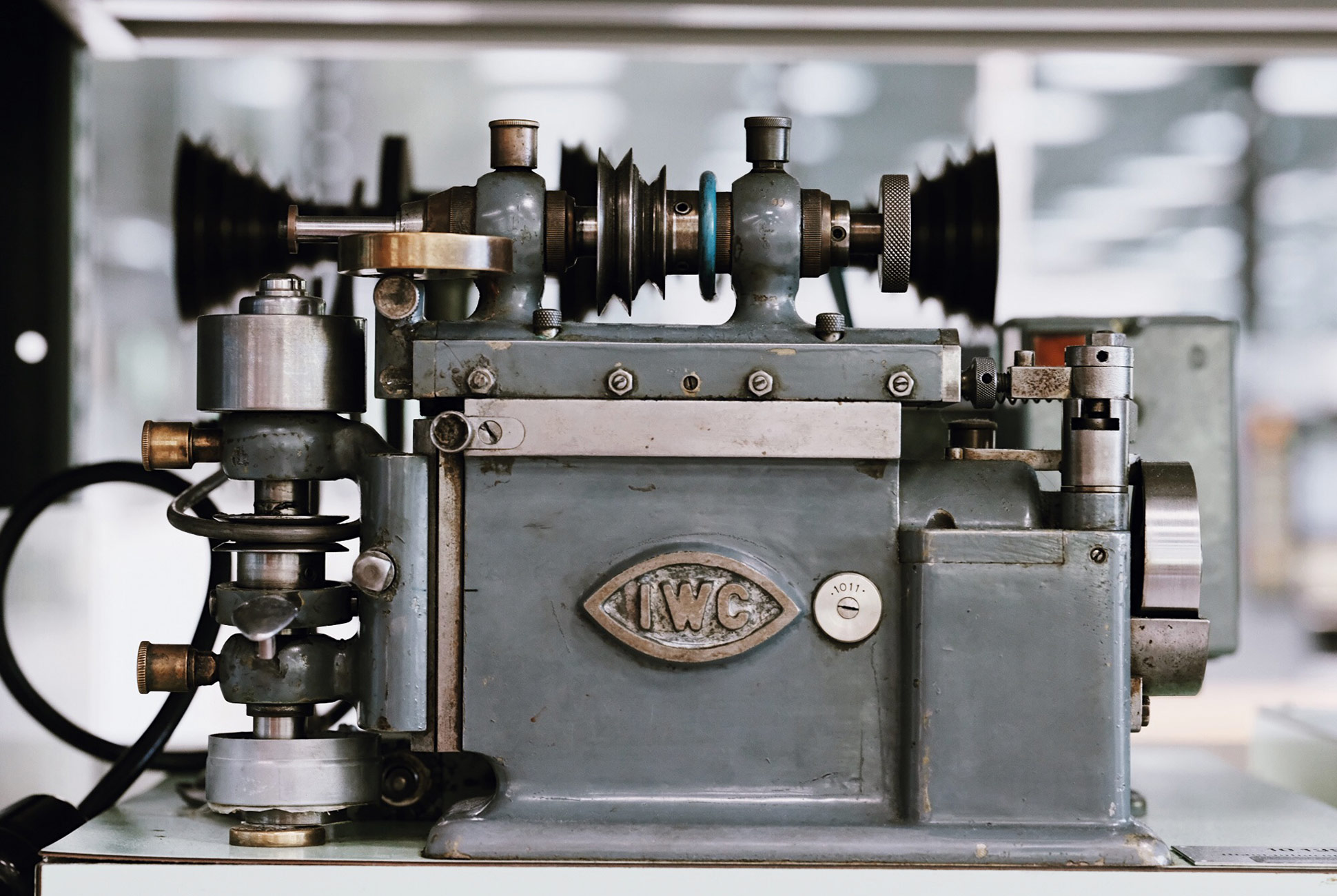

Sometimes the right tool for the job is an old tool. Though new machinery was purchased for the new Manufakturzentrum, much was also transplanted from IWC’s extant facilities. “Moving the machinery and workstations was a massive logistical feat that had to be meticulously planned and executed exactly on schedule,” says IWC COO Andreas Voll.

Some processes are still best left to humans, such as the application of perlage, or a pearl pattern, applied to movement components using a type of press. Though perlage is a decoration and can only be seen if the watch features a transparent case back, its application and presence is indicative of fine watchmaking. Other types of decoration are done using tools made in-house by IWC.

“For the next 150 years we wanted something forward-looking, something that felt light and luxurious, something that gives our staff and fans of IWC a home rather than just a place of work.”

Though movement component production is largely automated, pre-assembly, which involves piecing together the plates and bridges that constitute an ébauche (along with several other components), is far too delicate an operation for a machine, and must be done by hand. Once the ébauches are pre-assembled, they are sent to final assembly.

In planning the new Manufakturzentrum, Grainger-Herr wanted to be sure that there would be room to expand as the company grew further. “About 25% of the space is spare, which we will populate over the next year. For 10 or 15 years, I was always trying to squeeze our requirements into the space that was available — here we can do it the other way around.”

Though there are currently 230 employees working in the Manufakturzentrum, the new facility is built with modularity in mind and can accommodate up to 400 workers. Sustainability has also been considered, with solar panels, oil recycling systems, automatic LED lighting controls and a sensor-controlled automatic sunshade system contributing toward a greener workplace.

Changing rooms provide space for the IWC employees to don special jackets and shoes before entering the assembly area, which is a clean room Class VII environment complete with an airlock (50,000 cubic liters of air inside is scrubbed 10 times an hour). Because the pressure in the room is above atmospheric pressure, it is difficult for dust particles to enter.

Assembly and fine modulation (the initial setting of the time on a movement in five different positions) take place in a large room featuring rows of workstations, with each row of stations assembling one of five specific movement calibers (the workstations themselves are a custom development of IWC). Allowing each worker to focus on one specific task only lends a high degree of precision to the assembly process.

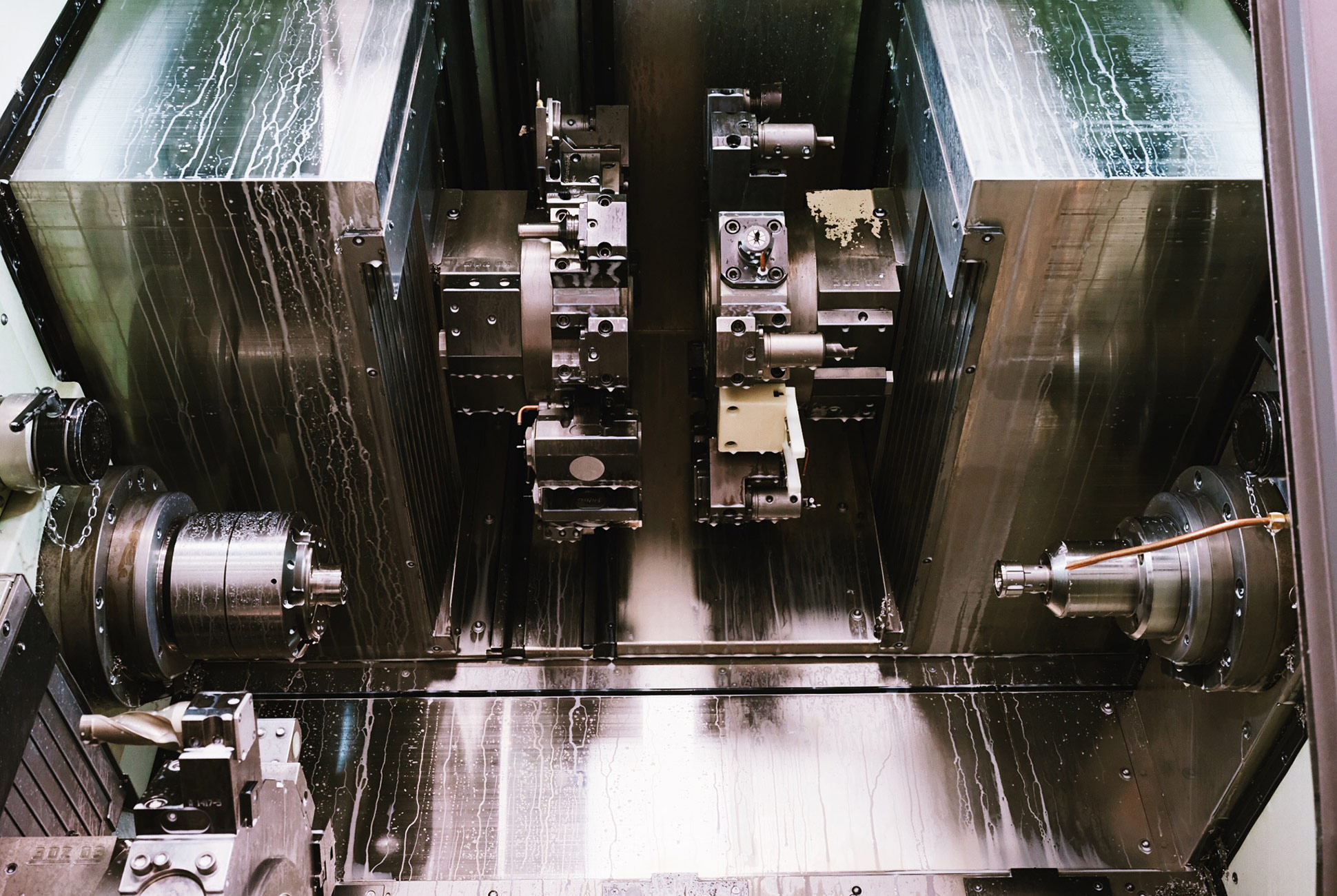

The lower level of the Manufakturzentrum houses the case production department, which can fashion watch cases from stainless steel, titanium, platinum, red gold, white gold, bronze and Ceratanium, a new titanium alloy that features the lightness and robustness of titanium, and the scratch-resistance of ceramic. Depending on the material being machined, a bar meter-long bar can produce between 30 to 50 cases.

Computer-controlled turning and milling centers are used to machine watch cases, which can sometimes require dozens of parts when bezels or chronograph pushers are involved. A central oil regeneration system is utilized in much of the Manufakturzentrum’s machinery, recycling some 12,000 liters of oil used as a lubricant, with a maximum output of 960 liters per minute.

Certain case materials are easier to mill than others — while stainless steel is comparatively simple to work, for example, platinum can take hours to mill to due its natural properties and complex geometry. IWC case production specialists are highly trained in these processes and are skilled in machining different materials.

After the machining stage, cases are polished and cleaned, and then receive a final inspection in a clean room environment. “Only the human eye is able to assess the quality of a surface,” says COO Voll. Machine engraving, etching and laser engraving are then used to engrave case backs, which allow for incredibly complex designs.

Moving almost all of its operations under one roof, including the production of specialized tools that aren’t commercially available, has been a tremendous boon to IWC. Says CEO Grainger-Herr: “We’ve seen this in the first couple of months, what a difference it makes, this shared idea of ‘Proudly made in Schaffhausen.’ That look in people’s faces — you can see that effect straightaway. It really helps tremendously.”

The finished product encapsulates all the incredible effort that went into manufacturing an IWC watch in the new Manufaktuzentrum: from machining the components, to assembling the movement, to cutting the case, to final assembly and regulation, an IWC wristwatch is a testament to the care and pride that every employee of the company takes his or her work.