LOS ANGELES — A sunny L.A. spring day is the ideal complement to taking possession of a nearly $500,000, Ambit Blue McLaren 765LT Spider. Add to that an hours-long midday stint on a nearly empty Angeles Crest Highway and a recipe is crafted for a nearly utopic automotive experience.

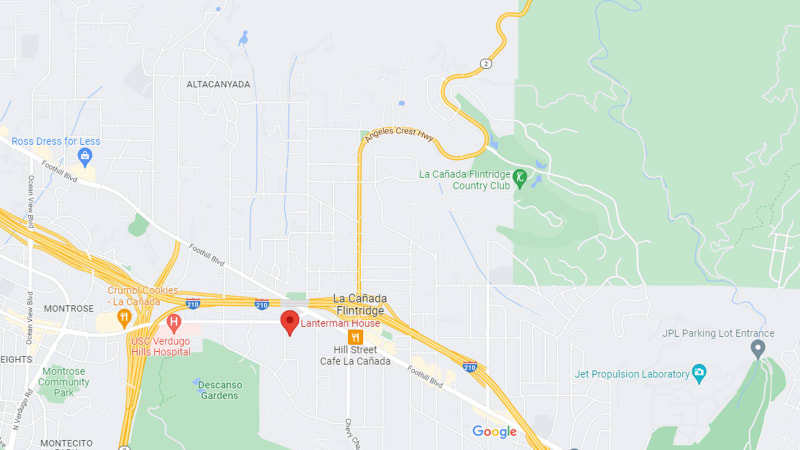

The presence of my boyfriend in the right seat was the proverbial cake frosting, save for the fact that he dislikes convertibles and driving quickly. We compromised. If he would join me for the ride, I would attend a museum tour with him at the Lanterman House in La Cañada Flintridge – a suburban town at the road’s western terminus – and treat him to lunch afterward. Drive, Discover, Dine: Date Day.

Dr. Jacob Lanterman moved to sunny Southern California from dreary western Michigan in the early part of the 20th century, seeking and espousing the health benefits – and relief from pulmonary illnesses like tuberculosis – believed to be offered by the lovely weather and fresh air. He became a major landholder in the Crescenta Valley, at the base of the San Gabriel mountains, built himself and his family a 10,000-square-foot Arts and Crafts-style home out of concrete and steel in 1915 to defend against the fire and earthquakes he’d witnessed in San Francisco, and began subdividing and selling parcels. But the valley’s lack of access to a year-round water supply choked the process.

His grandson, Frank, who lived in the house for his entire life, became a long-serving Republican California state assemblyman, and managed to pass legislation allowing the town access to the same fresh water supply that served Los Angeles, ushering into his pockets loads of cash, and ushering into the valley sprawl, traffic, and smog. Rep. Lanterman countered by introducing the nation’s first legislation mandating pollution reduction devices on cars. California thus became the first state to create tailpipe emissions standards, and require the componentry needed to scrub (some) harmful soot and fumes from the always-inefficient burning of fossil fuels. (Frank sponsored many less helpful initiatives as well.)

Speaking of the inefficient burning of fossil fuels, the McLaren 765LT Spider, which is able to pump 91 octane through its mid-mounted twin-turbocharged 4.0-liter V8 and produce 755 horsepower. And while it sports four gargantuan exhaust portals – lined up (and sounding) like the business end of a mortar – it at least spews far less air-corrupting garbage into the atmosphere than your grandmother’s LeSabre thanks to those tailpipe emissions standards, which allow the air surrounding Angeles Crest, while not perfectly clear, to generally no longer feel like grime stew.

This was a bonus for me during my reverential drive up and down the highway, as deep breathing is requisite when piloting a half-million dollars worth of peak British exotic through about 1,000 hairpin turns already occupied by hostile bicyclists, ripping motorcyclists, tumbling granite and suicidal wildlife.

It is difficult to enunciate the perfection of the 765LT Spider. I could critique the extortionate pricing like the $730 car cover, the $5,500 paint color or the $2,120 carbon fiber front license plate plinth. I could gripe about the fact that a car that costs this much doesn’t include Apple CarPlay. I could note that clambering into the car, and its highly-bolstered carbon-shell seats, requires contortions that would challenge a champion ecdysiast. I could whine that once you’re in there, there’s literally no place to put your stuff except a little webbed pocket on the firewall. But that would be nitpicking.

This car is an absolute blast, in the literal and figurative sense of the word. Acceleration is blistering – 0-60 mph arrives in 2.3 seconds, 100 in just twice that – enthralling and eminently repeatable. Though the car’s belt line was around my neck, forward visibility is shockingly ideal; one can practically see the road as it appears just beyond the front bumper, important when attacking the aforementioned blind curves. The braking, with ceramic composite discs, and calipers borrowed from the trackable Senna hypercar, is immediate, wonderfully balanced, and perfectly modulated.

The seven-speed dual-clutch transmission works telepathically in automated mode, but is far more alluring to rifle off shifts with the steering wheel-mounted paddles; in the sportiest setting they replicate a chiropractor’s adjustments. Grip is nothing short of agglutinate, aided by Pirelli P Zero Trofeo R tires, developed especially for McLaren, in sizes 245/35/R19 (F) and 305/30/R20 (R). Approaching their limits is like approaching the limits of the universe. And the engine, while not the most melodious, certainly sings. There is not so much a power curve as an inexhaustible reservoir of omnipresent vigor. One can mash the accelerator any time in any gear and experience the exhilaration of takeoff.

The last time I drove this road was in the Ferrari SF90 Stradale. The experience was very different, and it helped me understand why billionaires have more than one exotic. The Ferrari’s plug-in hybrid powertrain and all-wheel-drive grip made for even more astounding acceleration and handling. But the McLaren was more engaging, more of a connected partner. The Ferrari drove better, but the McLaren made me feel like a better driver. (Don’t ask my boyfriend if he would concur. He said his eyes were closed most of the time.)

Also, the McLaren is a convertible, which – despite the protestations of bitter naysayers who despise joy – makes every road car better. It allows occupants to be immersed in the world, to exhilarate in life-giving energy as the scenery rips by. And it allows them to enjoy the air. We can thank Frank Lanterman, in part, for that.