Sit around a campfire long enough and you’ll eventually hear a tale about the Forge, an almost mythic building at Patagonia. Named after the tin shed that Yvon Chouinard used to make climbing pitons in the late ’60s, Patagonia’s Advanced R&D Center is filled with a half century of folklore, wild ideas and nixed prototypes that never saw the light of day. Yet because most of the work done in the Forge is years from retail shelves, few know what actually goes on inside.

“It’s both an art and a craft to design the future of outdoor apparel, but saying that sounds pretty intense,” observes Glen Morden, the brand’s VP of product innovation, materials and development — a.k.a. the guy who runs the place. “The Forge is a safe place for tinkering and a resource for the entire company to try new things. We use it to create new products and improve what’s already out there. It’s where we created the Micropuff Jacket, the new Descentionist Pack and Das Parka, to name a few.”

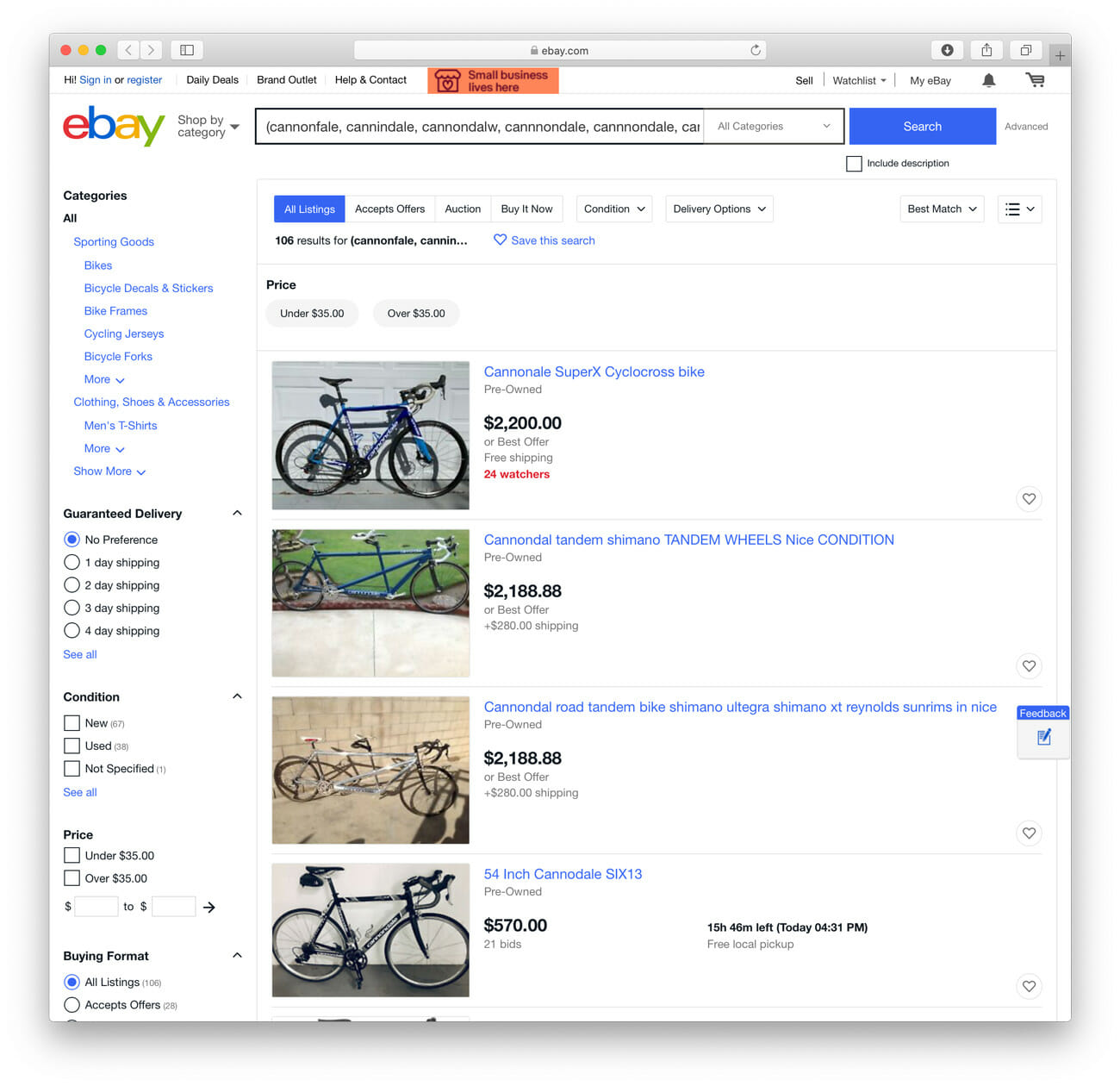

These materials represent the building blocks of protective face masks.

Since its formal establishment over a decade ago, the Forge has become the heart(h) of the iconic brand, helping develop nearly all of the leading edge and highly technical products made by Patagonia. It’s the nucleus of product creation and a library of knowledge about materials, form, fit and production.

“The space replicates a manufacturing floor, which helps designers test things at scale,” Morden explains. “We have every machine here that’s in our manufacturing centers and a support staff of engineers and technicians who run them proficiently. The core team is just 25, but many more pass through every day.”

Shifting Gears in a Crisis

On the cusp of diving into the good stuff — future shells, synthetics and proprietary secrets — Morden pivots to the elephant in the room: COVID-19. Like all “non-essential” California businesses, Patagonia shut its doors on March 13th, when the governor announced the state’s shelter-in-place order. Employees, including all of the designers who work at the Forge, were tasked with working from home.

Prototype engineer Justin Mills takes a look at a whole lot of face mask fabric.

“Right away we wanted to make a meaningful contribution to the escalating pandemic, but we took a cautious approach,” Morden says. “The first rule of an emergency is to stay out of the way of professionals. We did a lot of research to make sure we were adding value before jumping in. We wanted to maximize our impact with the tools we had in front of us. We landed on two projects — two different avenues of mask production.”

Patagonia was given an exemption from the state to re-open the Forge, but with safety the top priority, production ramped up slowly. The team started with machines that could be run with very few operators and spread sewers across the large space, trying to be as careful as possible. As specific needs for masks became more clear, the team and system grew methodically.

“It wasn’t that challenging to convert the Forge into a production facility, but we want to do it safely,” Morden stresses. “It’s a concept studio that’s quite limber. We took a lot of lessons from our Reno distribution center and, almost ironically, already had 4,000 square feet empty because we were in between projects.”

More than 40 employees, working in shifts, have donated their time to the mask-making operation.

Crafting Fast for a Cause

For a team of designers that focuses on products years out, this was a new challenge. Fortunately, everyone on the advanced R&D team has a home studio with a sewing machine, so prototyping form factors started quickly. Within 48 hours, they had mask samples using common Patagonia fabrics and by the end of the week had landed on a final concept.

“It’s all a volunteer effort,” Morden says with pride. “We have over forty employees that rotate through shifts, ten at a time. Shifts are four hours long to allow those with children to juggle responsibilities. The team includes people from all over the company.”

All of the face masks made in the Forge use fabrics Patagonia already had in large quantities. Echoing the ethos of the Worn Wear program, the brand wanted to use available materials. The current mask design employs a Nano Air face fabric paired with a Capilene lightweight lining. It’s intended to be a comfortable, durable and reusable civilian mask.

Ardith Carter, who works in quality management for Patagonia, volunteers her mask-making skills.

“The first thousand masks had a two-strap design that went around your head, and it evolved to elastic around the ear,” Morden shares. “We started by making masks for our distribution center staff and they gave us feedback on comfort and fit. They wear masks for eight hours every day and had a lot of input.”

The team in the Forge is also repairing 20,000 N95 medical grade masks left over from the 2017 Thomas wildfire. These masks will be sold to the city of Ventura for $1.50 apiece, barely letting Patagonia break even. Meanwhile, Morden’s overarching goal is to make a quarter-million civilian masks in the next three months, but the bottleneck is machines.

Alex Wasbin, a Patagonia designer, lends his sewing talents as well.

“We’re talking with our manufacturing partners about making masks to help us scale up faster,” he says. “As we look down the horizon and consider what the outdoor community will need; we start to wonder if a sport mask and other safety tools will be necessary.”

Then Morden says something that puts a bow on just how dramatically this operation has changed things up, in a good way: “The Forge typically works on projects three to five years out. Now we’re working three to five days out. We’ve never lived more in the present.”