From Issue Six of Gear Patrol Magazine.

Discounted domestic shipping + 15% off in the GP store for new subscribers.

Lauren Woods Limbach’s eyes light up when discussing her closest buddies at work. There’s Ol’ Dirty Bastard, “who’s weird every single time,” she says, gesturing in his general direction with her long arms, taut and muscular from rock climbing. Gilda the Golden is just “amazing,” while Lady Marmalade is absolutely, positively a favorite. As for Pixie Dust, she’s “screaming sour,” Limbach says over Los Lobos coming through a loudspeaker.

In most workplaces, this character defect would merit HR intervention. At New Belgium’s Fort Collins, Colorado, outpost, Pixie is a perfect employee, as reliable as spring rain. She’s one of 65 foeders, massive oak barrels that fill New Belgium’s wood cellar from concrete floor to ceiling. They contain beer steadily acidifying, growing funkier by the day, thanks to the transformative magic of souring bacteria and wild yeast.

Limbach serves as the beer’s caretaker and shepherd, directing it to its final destination: your stomach. As New Belgium’s wood-cellar director and blender, she leads a three-person team blessed with precise taste buds and noses that’d make a bloodhound jealous. They parse each beer’s sensory profile and blend complementary brews into a sum so much more sublime than its parts. Exhibit A: the La Folie being bottled right then and there.

The puckering brown ale fuses beers that have aged up to three years into a complex symphony of plums, citrus, green apples and sweet caramel. Constructing the beer is a game that Limbach has mastered. “Blending to me is kind of like chess,” she says. “I have sixty-five foeders and two hundred small barrels, and I need to know where they were from the beginning in every single way in order to move all the pieces in the right way.”

Blending is among brewing’s most essential, misunderstood and pervasive facets. Sour beer may be an obvious example, but most every barrel-aged barleywine or stout is made from a mix of barrels. Larger breweries combine huge batches of beer to create consistency. By adding water, brewers can dampen a lager’s unwanted sulfurous aroma or dilute a boozy beer. IPAs’ distinct scents are derived from distinct hop blends. Moreover, breweries are merging different beer styles to stake flavorful new ground. “Blending is a massive part of creating every beer,” says Firestone Walker brewmaster Matt Brynildson.

Sour Beer’s Sweet Science

Blending beer is nothing new. Irish bars serve black-and-tans, layering Guinness over lighter lager. In long-ago London, bars would combine sour stock ale with sweeter mild ale, a mix tailored to customers’ tastes. Belgian gueuze, on the other hand, is a blend of spontaneously fermented lambics that are one, two and three years old — old funk meets youthful vibrancy.

Famous Belgian blenders such as Tilquin buy lambics and make bespoke concoctions. In 2016, that inspired James Priest to found New Jersey’s Referend Bier Blendery. His plan had just one small problem. “We don’t have the luxury of being able to buy bulk lambic,” Priest says. “We had to start from scratch.”

He bought a coolship (basically a large, shallow baking pan), which he now trucks to breweries. They fill it with steamy wort, the sugary grain broth that becomes beer; as it cools, native microbes feast, starting fermentation. Then, back at Referend, he transfers the spontaneous ferment to barrels, where the liquid starts an uncertain flavor journey.

Even if three barrels contain identical beer, results can vary wildly. One may flaunt diamond-sharp acidity, while another might be mineraly or boast lingering bitterness. After appraising his barrel stock — envision ingredients in a pantry — and settling on a desired flavor profile, he builds his blend, seeking complementary parts. “I target my six or seven favorite individual barrels in the cellar across these different ages, then I’ll play with those to see what will meld the best,” he says. Most of his barrels, he explains, “work better together than as a single component.”

Creating and blending sour and spontaneous beers is fast gaining popularity across America. Austin’s Jester King, Denver’s Black Project, Tillamook, Oregon’s de Garde Brewing, Southern California’s Beachwood Blendery and Side Project in St. Louis are some of the hottest names in brewing due to their deftly blended, multifaceted beers.

Still, few breweries have done it better or longer than New Belgium. “Blending beer, whether it’s for efficiency, romantic or experimental reasons, has always been in our DNA,” says Specialty Brand Manager Andrew Emerton. Last year’s Blend Like a Brewer variety pack encouraged consumers to mix beers like brewers do for post-shift drinks. Sour Saison, the brewery’s first year-round traditional sour, combines a rustic farmhouse ale with foeder-soured farmhouse ale. Meanwhile, Transatlantique Kriek, an international collaboration now in its 15th year, is made by importing cherry-infused lambic from Belgium’s Oud Beersel and fusing it with New Belgium’s own Sour Golden Ale.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of La Folie, its makeup as tattooed on Limbach’s brain as the necklace of flowers is around her neck. “La Folie is so specific in my head,” she says. “I’ve never written down what I’m trying to go for, but I know it. I know when I taste a barrel. It’s like, ‘Oh yeah, this is for La Folie.’”

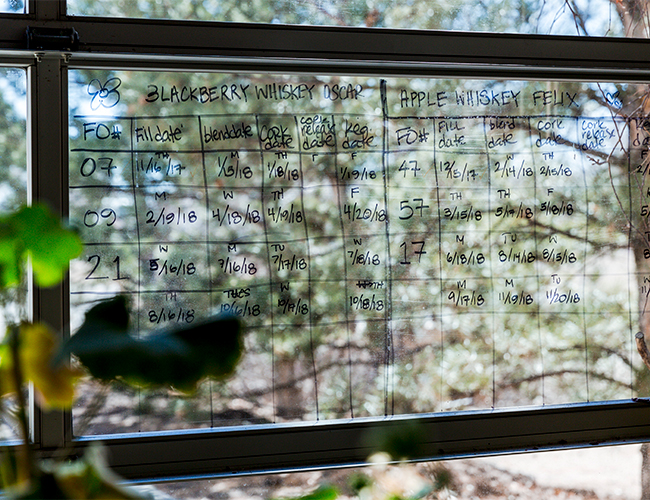

Her La Folie blends start when the foeders are filled with a dark lager named Oscar. (The other base beer is Felix — an Odd Couple reference — that’s earmarked for Le Terroir, a dry-hopped sour.) She knows some foeders’ acidic trip will take around nine months, others 12 or 16, so she roughly forecasts liquid availability some four years out. “The least romantic thing you can possibly say with blending is ‘spreadsheet,’” she says, laughing.

These numbers are approximations. foeder beers brim with live flora that acidifies beer along an idiosyncratic timeline. Vessels filled in winter mature more slowly and accelerate come summer, while summer fills start fast and then slow down. “A wintertime versus a summertime fill will taste totally different,” Limbach adds. However, one foeder by Limbach’s desk worked in reverse, a situation that left her flummoxed.

The light-bulb moment was literally that: light. The foeder was hammered with winter sun and squatted in summer shadows. “You fill her in the winter, and she acts like a summer barrel. Fill her in the summer, she acts like a winter barrel,” Salazar says of Soleil — French for “sun.”

Keeping tabs on every two-story giant is tough. Some barrels sit out of sight, overlooked and under-loved, until they make you perk up. “We call one Stepchild, because we always forget where it is,” Limbach says. She never remembered to taste it and when she finally did, the flavor was a dud. “It did something terrible and everybody noticed. We gave it a name and now it’s pretty happy.”

Her eyes play a significant role in understanding when beers are done. She pours several foeder beers. One is cloudy, the other nearly see-through. “I know this one is almost ready,” she says of the clearer sample. When the time comes to finalize a blend, Limbach pulls numerous samples and tastes them blind, closely confabbing with her partners Eric Salazar and Ted Peterson on what they find interesting. “Being a blender-of-one is just no fun,” she says. After factoring in analytics such as expectations and demands, the blend is built with Limbach acting as sensory specialist and seer. “I need to make sure the liquid is going to bottle-condition perfectly and will stand the test of time and stay delicious — even if it changes,” she says.

Lauren Woods Limbach sketches out part of her production schedule on a sunny garage door near her office. The contents of her wooden tanks are forecasted four years out.

Consistently Unsurprising

As America’s industrial-lager complex accelerated in the mid- to late-20th century, blending became a means to end. It sanded flaws smooth, eradicated the off flavors. Producing same-same beer can seem soulless, but the process instills consistency, a desired trait in large-batch pilsners and pungent IPAs alike.

Dogfish Head is famed for palate-exploding beers such as 60 Minute IPA. It’s a paradigmatic East Coast example, pine-charged and plenty citrusy, with sturdy malt sweetness to balance bitterness. Fans return to the icon time and again because, like dinner at a favorite restaurant, it dependably delivers the expected flavor. “For us, we expect the beer to be the same every time, and that’s what our consumers expect,” says Dogfish Head brewing ambassador Bryan Selders. “They’ll notice if a batch of beer is slightly awry.”

Many modern breweries release beers faster than an auctioneer’s spiel, recipes rarely repeated. Dogfish Head is no slim start-up, its huge fermenters filled with multiple batches of beer, hundreds of thousands of 12-ounce bottles in total. To ensure everything is up to snuff, and sniff, beers undergo constant sensory evaluation throughout fermentation. After fermentation, different batches are blended and filtered to remove particulates and create a clearer beer. “We really think of blending as the best means by which we can achieve consistency of flavor in all of our brands,” Selders says.

When Firestone Walker’s Brynildson attended brewing school in the mid-’90s, blending was scarcely on the syllabus. “Blending was almost a negative thing, like that’s how you fix problems. You blend them off,” he says. “Nobody was talking about lambic brewing and blending’s historical traditions.” Brynildson began in Chicago at Goose Island. But twists and turns took him cross-country to California’s Firestone Walker, situated in Paso Robles — smack in the middle of the winery-rich Central Coast. In 2006, Firestone Walker commemorated its 10th anniversary by enlisting winemakers to help blend various barrel-aged stouts, IPAs and barleywines.

“I saw this as an incredible opportunity to learn from people who, I felt, were expert blenders,” he says. They met expectations, combining oak-aged ales to create one with a neat cherry note that was nonexistent in individual beers. The alchemy freed Brynildson. “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I even have the ability to blend beers in my clean cellar,’” he says of brews untouched by wild yeast. “There’s limitless opportunity.”

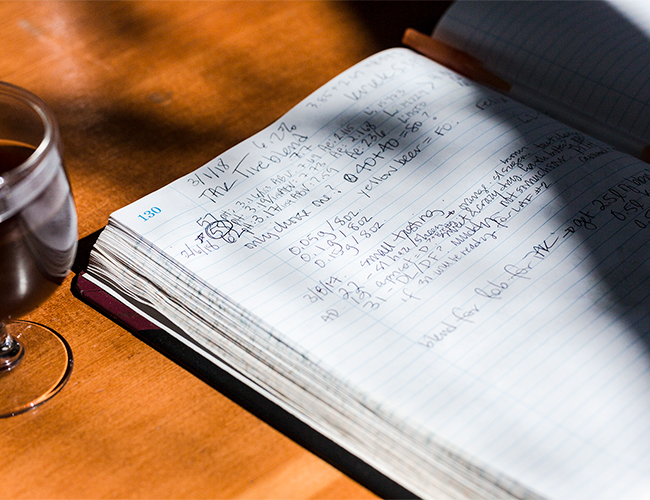

For Limbach, the only way to understand a beer is to get up close and personal, using her highly trained nose to decode its aromatic signature. She draws on the written works of a perfume expert to help verbalize flavor and fragrance.

The brewery’s British pale ale, DBA, had long been partly fermented in an oak-barrel system and melded with stainless-steel-fermented beer. Brynildson started fashioning other formulas, combining a basic pale ale with DBA to create the lightly oaky Pale 31. “The combination of two beers creates something that’s really unique,” he says.

Blending takes numerous forms at Firestone Walker. Sometimes, its brewers create strong wort and weaken it by adding water, which they’ll also add to lagers that might be too sulfurous. Furthermore, Brynildson and his team are forever playing around with hop blends, adjusting as new varieties become available and popular tastes change — dank and bitter to fruity and tropical. “Even if we came up with this blend three years ago that we really liked for a particular beer, we’re always putting those hops back on the table and seeing if they’re consistent with where we want that beer to be,” he says.

Special Little Butterflies

We’re in an era of overwhelming choice, with some 6,000 breweries in America and counting. Flavorful differentiation is nearly impossible, what with the same hops, grains and yeast strains available to all. Creating unicorn beers requires a little creativity.

“In today’s landscape of beer, there are so many different breweries making great beer. If you don’t have something that’s unique, you just become another beer on the shelf,” says Matt Van Wyk, a brewmaster and cofounder of Oregon’s Alesong Brewing & Blending. “When you’re blending two different beers that weren’t typically going to go together, it can make something new that’s never been seen.”

Alesong specializes in limited-edition beers that take drinkers on a flavor trip. For example, the brewery aged a wild yeast-spiked saison in gin barrels; it picked up notes of juniper and citrus. Samples evoked the citrusy French 75 cocktail, so much so that Alesong amplified the profile with lemon zest and a distillery’s spent botanical mix. The final blend was a bartender’s dream.

“You think about a base beer, and you think about where it’s going to end, but you don’t really know until you wait and see how the yeast reacted, or just the barrel itself,” Van Wyk says. “After blending experiments, you may take a whole different direction with the beer.”

Alternatively, Dogfish Head designed SeaQuench Ale as a blended beer. The tart easy-drinker combines three distinct beers: a snappy kölsch, salty gose socked with black limes and coriander, and an acidic Berliner weisse laced with lime juice and peel. The beers are brewed separately and jointly fermented, “building complexity that we wouldn’t be able to achieve if we brewed it from one master recipe,” says brewing ambassador Selders. “It’s a singular drinking experience.”

Peter Bouckaert sees singular drinking experiences in a different light. Late last year, New Belgium’s longtime brewmaster left to cofound Purpose Brewing & Cellars. The Fort Collins brewery creates barrel-aged beers based on moments and inspiration, using unlikely ingredients like sundried tomatoes, spinach, coconut flour and roses to develop novel aromas and flavors. Most beers are served unblended, some directly from the barrel, as flat as the day is long. “It’s really fun to surprise people [with] what a barrel-aged beer can be,” he says.

By serving single barrels, Purpose rarely has leftover liquid. On the other hand, blenders are sometimes saddled with delicious excess. Say the ideal mixture is two-thirds of one barrel, one-third of another. What happens to the rest? “You’re thinking, ‘I can’t put this down the drain because it’s still good beer, but I don’t need it to blend with that,’” Van Wyk says. He’ll transfer excess beer to kegs and send them to cold storage until needed. “You have to figure out what to do with them.”

Back at New Belgium, Limbach adds another challenge to the mix. Brewers with oodles of small barrels can’t conceivably taste every one prior to blending. “There will always be duds in a blend. You just hope that it all evens all out,” she says. Limbach looks over her oak forest. “These guys, ninety-nine percent of the time they don’t let you down.”

She’s been around her friends long enough to know that Gilda the Golden will always exceed expectations. Little Richard’s sourness will make tasters go “ooo ooo!” And Bill Withers, just like the singer’s best-known song, only wants to be used again and again, delivering his singular flavor no matter if brewers are playing Chuck Berry or doom metal. They’re happy here at New Belgium, where the distinct personalities get along famously and are kept happy by their constant companions.

“I don’t like to anthropomorphize because I know it’s silly,” Limbach says. “On the other hand, I feel like the more I’m with a foeder, the better the chance it’s going to do something great.”