R

ob Melville has been on his feet and on his game all day at the Geneva Motor Show, doing interview after interview inside McLaren’s large, luxurious lounge next to the Roll-Royce booth on the Palexpo convention center floor. It’s mid-afternoon and we’re sitting in a small room tucked in a hallway off the bar area, and he seems glad for a moment of quiet. But when we start talking design, Melville launches in with gusto — he’s proud of his craft, and for good reason.

I’d spent the three days prior to our conversation driving a caravan of McLarens across five countries in a 900-mile road trip from the UK to Switzerland, admiring the countryside as much as the sinewy beauty of the various cars at our disposal. The 570S, 570 GT, 570S Spider and 720S we drove are all Melville’s designs, as are the new Senna and wild Senna GTR Concept at the show. In a world awash with curvy and aggressive supercars, their shapes and lines stand out as something different — something purposefully, functionally beautiful. As I spoke with him about his design philosophy and what it takes to create the insane shapes for the British brand, Melville, in an eloquent lilt, waxed on about classic cars, architecture, running shoes and virtual reality.

Melville’s McLaren designs are informed directly by biology.

When we grow up we’re surrounded by nature — and you have this intuition for why a bird’s wing works or why a teardrop is the way it is. The way stones are formed by the sea — hydroformed — or formed by the air.

When we talk about biology in the P1, 570 and 720 it’s [as though] you have the chassis — that’s the skeleton — or the lungs, which are the radiators. Then you’ve got the skin and the aerodynamic profile. Senna is [the result of asking] “how do you bring every last drop of performance out of a road car?” Our ability to analyze [the laws of aerodynamics] and understand them have informed our decisions on the car.

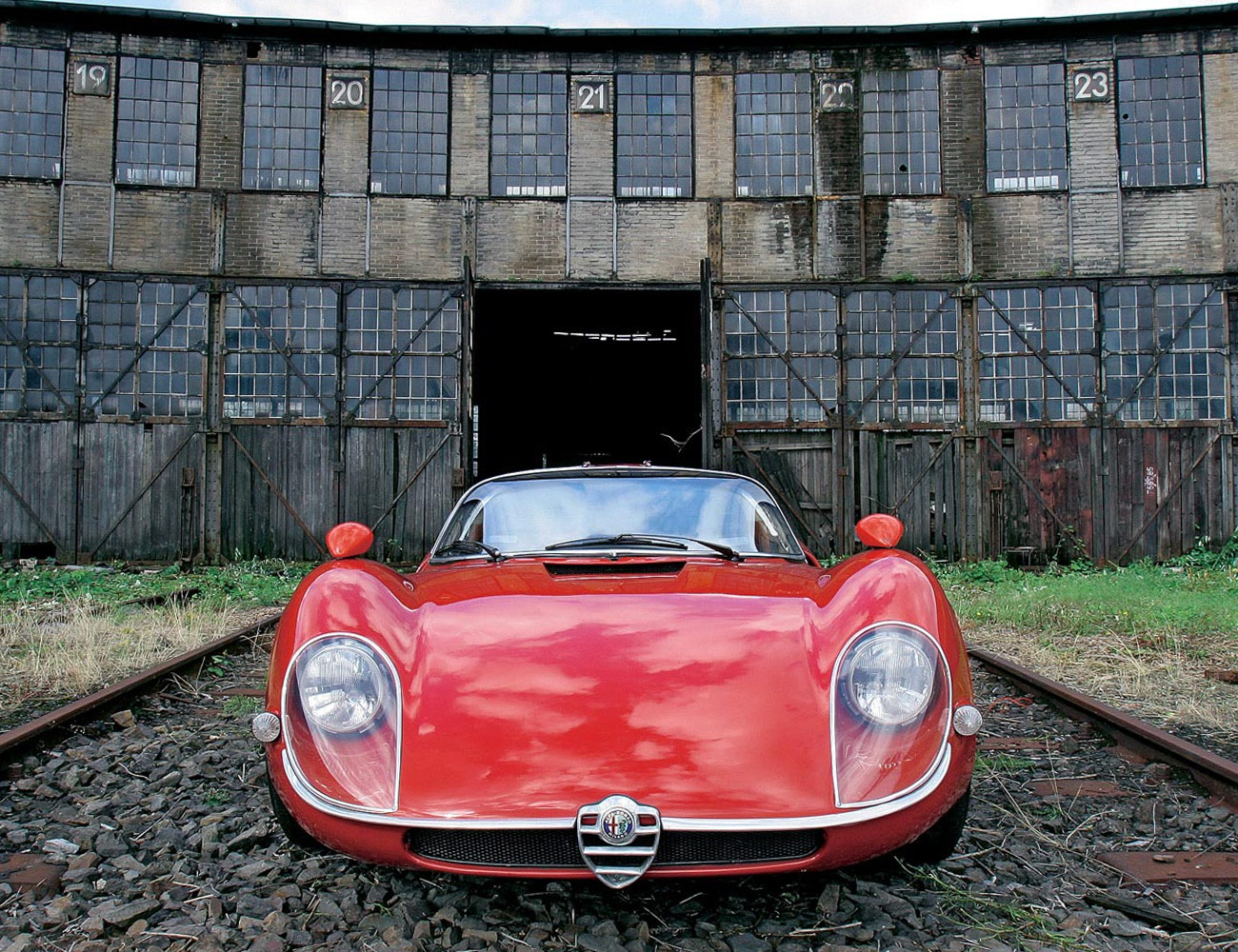

The Alfa Romeo Tipo 33 Stradale

They just don’t make ’em like they used to.

I think within the automotive [industry] it’s hard to find other examples [of the biological approach]. You’d probably have to go back in time, I think, to find them: Facel Vegas, my favorite car of all time the Alfa Romeo 350 Stradale. Really just so shrink-wrapped … so muscular, but big, bold, simple volumes. And you can see that intuition with the lines and profiles is based on [designers] growing up and being surrounded by nature.

In the modern day [this approach] is kind of gone in terms of that visual intuition. I’m sure they’re equally as efficient. I bet if you were to measure them the old cars are higher up; the tires are tucked up into the body. As a pure basic approach, I don’t think [the industry as a whole] is as close as they were. I think McLaren stands out for that alone.

Nike Allyson Felix Track Spike; photo by Nike

Nike and other shoe designers have directly utilized biological designs in concepts.

In terms of product design, I find some of the things Nike have done quite interesting. They’ve done some concept track shoes about two or three years ago. They were 3D printing the soles to take weight out — ultra lightweight. The actual structure goes up around your foot so you don’t have any lateral slip. It’s got a whole bone structure thing going on [after] you’ve taken all the weight out of those studs or spikes around the bottom. That’s probably the best example I can think of in terms of products where you can see a clear connection.

If you go around design colleges you see a lot of people working on [things like] high heel shoes. [Architect] Zaha Hadid did some based on that principle. You can see it’s carved away, completely abstract volume of what a shoe is. Everything [on top] was all blocked in; everything [on the bottom] was all open. It’s kind of like reversing the graphics.

Zaha Hadid’s architectural designs employed an inside-out philosophy.

Zaha Hadid has inspired quite a lot of the cars we’ve done. She was quite artistic in her approach. Shapes are kind of really fluid with integrated functionality. So one of my favorite buildings is the cultural center in Baku, Azerbaijan. The steps that lead up to it eventually become the building itself, and it’s based on the italic writing of the region so it’s got a cultural context. At the same time it blends out into the public landscape, so you’re already walking on the building and eventually, it peels up and you’re walking inside. There’s this beautiful depth.

Heydar Aliyev Center — Baku, Azerbaijan; photos by Iwan Baan & Helene Binet

Then when you’re inside that theme continues and … on the floor molds up into the ceiling and lights go from the floor all around. Very thin LED strip lights. You have this seamlessness, blurring the boundaries and it’s engaging. Kind of makes you go “wow.” I’ve never been, but I’ve done virtual tours and things. I never get out of the office. [laughs]

There are two ways to begin a car design.

The definition of design is ‘people who make drawings of things to explain how they work.’ To me, design is where art and science meet. I think you can approach it from either end. Sometimes, when we draw something it just looks stunning — people go, “oh we could make that work; how do we engineer it?” The other way is to come up with a complete package first and very quickly envision what the attributes are. You can approach it that way and say, “okay, can we make it look beautiful?” At McLaren, we try to do both, because … they’re all supercars. They [need impressive] downforce, feedback, grip, dynamics and needs to be beautiful. It can be brutal and functional or it can be beautiful and functional. Both can have an appeal.

The Ferrari F40

Go back to the [Ferrari] F40 in the past and … it was as aerodynamic as Ferrari could make it at the time. And I think with McLaren, the F1 was also as aerodynamic as we could make it at the time. It had a lot of great attributes — low base of screen (windshield), low cowl so you had great visibility.

So you can approach it from either side. Again, we’re trying to blur the boundaries. We don’t want to be a silo of “well, this is a beautiful drawing,” because to me that’s styling — [then] we’re just drawing shapes. We could do some ergonomic studies; a lot of the design studios will have an ergonomist to engineer some aero. But at McLaren we work so close together – we literally sit next to the engineers. It’s far more holistic.

Aerodynamics dictate that McLaren radiators are oriented sideways. Isn’t that inefficient?

You need a lot of air. Ideally, I’d have [the radiator] positioned perpendicularly to the airflow; direct into the airflow. As a designer you want it to be efficient, simpler but better. Any opportunity to square them up, we say, “let’s do it if it’s more efficient.”

The McLaren Senna GTR Concept; photo by Nick Caruso

If you break it down into two parts, one is ‘where do you start in terms of design thinking’? They can come from either way: a measured approach or an artistic approach. Then there’s ‘where does is start in terms of a toolset’? If we’re going to start in the studio, ideally we’d have a basic package: does [the car] have two people? Does it need one seat? Three seats? We can do that with studio engineers.

The McLaren design studio is extremely advanced, right?

The latest technology we’ve gotten in is being installed as we speak: the VR headset. [That technology] has] been in the news for years now. But what we’re doing differently is we’ve developed a tool that’s just for McLaren. The question was ‘how do you redefine what a designer’s desk should be for this day and age’? You’ve got a headset on your desk.

The McLaren Senna; photo by McLaren Automotive

Ultimately, we need to get from an idea to a surface. Where we’re really strong too is that intuition. My aim is to give everyone the tools to maximize creativity.

You plug yourself in, and get the engineering package in 3D in real time. [You can see] every nut and bolt; you can go all the way down through the steering column if you wanted to. In the old days, we’d do a tape drawing. [In VR] you can sketch, build up the center lines, curves and sections of the car. Then click and go full size and stand outside, looking at the car full size then go back down to the scale model. I’m just in my little world.

Aston Martin CEO Andy Palmer lives the life of a charmed gearhead: he owns and races Astons, travels the world talking about cars and under his watch, Aston Martin has become one of the fastest-growing automakers in the world. Read the Story