Thirteen years ago, no one had heard of TRX. Today, it is one of the most in-demand at-home workout tools, backed by a company boasting more than 100 employees and annual revenues topping $50 million. Not surprisingly, the brand’s popularity has spiked even more of late, with search queries up over 100 percent for TRX bands, TRX full body workout and TRX workout plan, according to Google Trends.

The man behind the straps? Randy Hetrick, a former Navy SEAL, who mistakenly brought his jiujitsu belt on a deployment — and ended up creating a fitness sensation.

We caught up with him to learn the full origin story.

Belt It Out

More than 20 years ago, Hetrick was deployed in a warehouse in Southeast Asia. On a SEAL mission that was supposed to be brief, but quickly changed course, he found himself spending too much time… killing time.

“That particular deployment was supposed to be a quick in-and-out, a counter-piracy operation,” he recalls. “And it ended up becoming protracted, as they often did.”

“I had this weird spark of inspiration to go tie a knot in the end of the belt, throw it over a door, shut the door, lean back and see if I could create the movement of climbing up a ladder.”

In search of a way to train his climbing muscles, Hetrick found inspiration in an unlikely place.

“We would always deploy with these boxes of spare gear, so you’d have a roll of some nylon webbing that the riggers used to prepare parachute harnesses with,” he explains. “You’d have duct tape, 550 cord, [and] we’d just have a lot of different stuff in a spare kit bag. And I had accidentally deployed with my jiujitsu belt because I had scooped it up underneath my flight suit.”

What initially seemed like a waste of space became the key to a DIY workout modality.

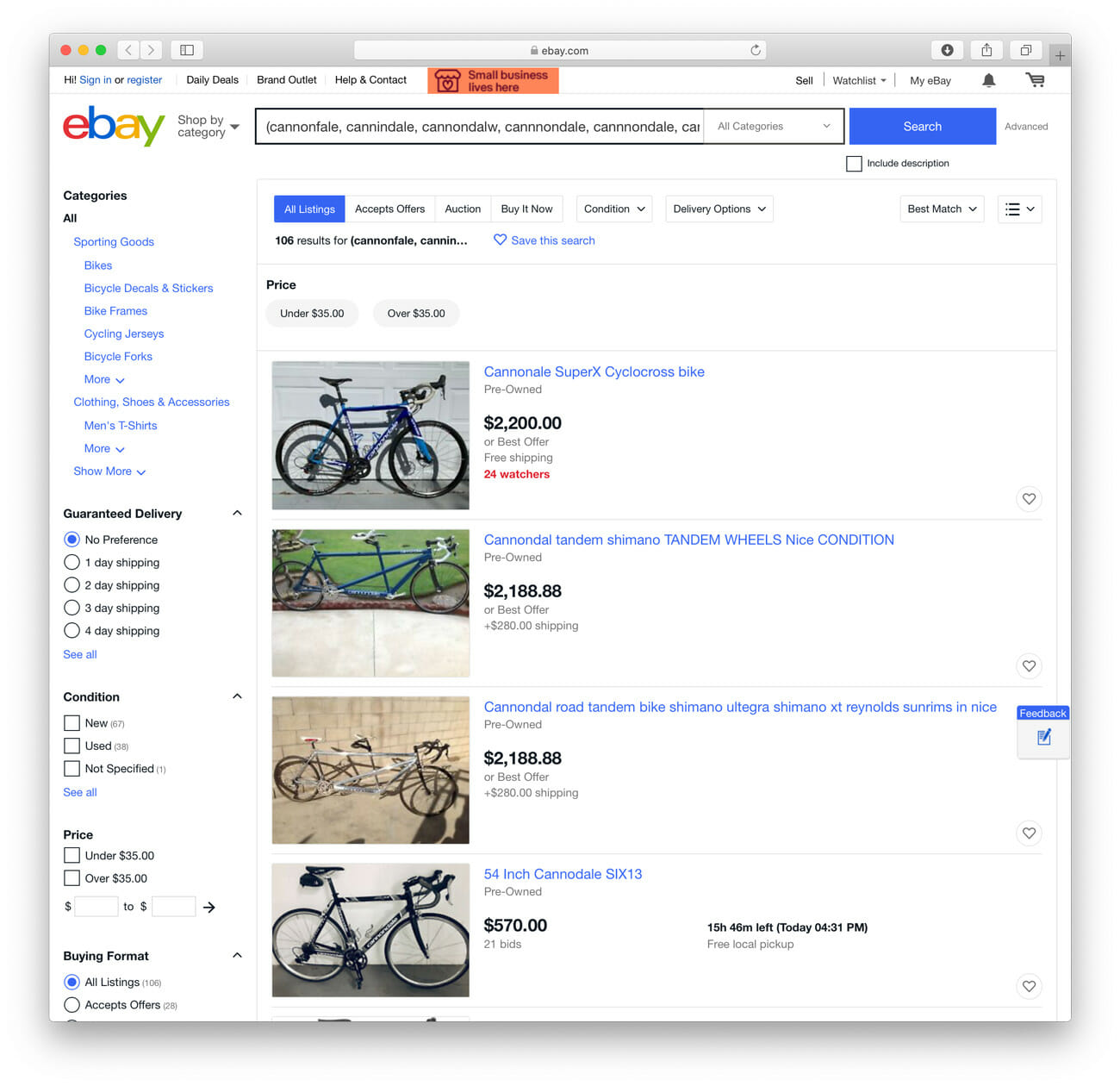

Hetrick puts “suspension training” to the test with the original TRX strap back in the ’90s.

“I had this weird spark of inspiration to go tie a knot in the end of the belt, throw it over a door, shut the door, lean back and see if I could create more or less the movement of climbing up a ladder.”

In essence, he figured out how to use gravity and his body weight as fitness tools. It helped the team on the mission, but at first, Hetrick thought nothing more of it.

“I trained on it like a beast all during that time [1997 to 2001], as did other guys in the squadrons,” he says. “It started getting popular. But it wasn’t as evolved as it is today. It was really just an upside-down Y, with no real adjustability. The original design had a carabiner, and a little bit of adjustment on the suspension anchor. The arms of it didn’t adjust. It was a crude predecessor. But it was great, and guys loved it.”

Hetrick would make the early iterations of a TRX strap for his compatriots in exchange for a case of beer.

“I was running a squadron, but I loved the fact that guys thought it was clever, and they wanted me to make them for them,” he says. “And so that was fun.”

Campus Craze

After 14 years with the SEALS, Hetrick left and attended business school at Stanford. While there, he spent a lot of time training with his TRX straps in the athlete center (not the campus gym), where he was asked by practically every coach why he was there — and why he was so old.

“ ‘Suspension training’ wasn’t a phrase thirteen years ago. I kept trying to explain to people how this thing worked. There was no precursor.”

“I was 36, and everybody else, all the student athletes are 18, 20,” Hetrick says. Once a classmate, a tailback on the football team, explained to the coaches that he was an old commando, they let him use the facilities. And then they wanted to know what on earth he was doing.

“Stanford has a pretty sweet weight room, and yet I would be in there with straps hooked up to the squat rack, busting these workouts,” Hetrick says. “And every coach I ever talked to would ask me if I could make them for their team.”

The prototype was about 30 percent canvas strap and carabiner, 70 percent jiujitsu belt.

So Hetrick did, and soon 300-pound linemen, female tennis players a third third size and everyone in between would use them. That’s when he realized he might have a viable product on his hands. But first, he needed a name.

“We military guys love acronyms, that’s a law of nature,” he jokes. “But the more serious answer is… imagine you and I are riding on a plane together, and you’re like, ‘So what do you do?’ and I’m like, ‘I run a little startup that produces gear.’ And so this conversation progresses, but then you end up saying, ‘Okay, wait, it doesn’t have weights?’ ‘No.’ ‘Oh, so it’s a rubber band?’ ‘No, no, it doesn’t stretch.’ You’re like, ‘Well, wait a minute. It doesn’t have weights and it doesn’t stretch, then how does it work?’ ”

Over time, Hetrick started to call it a total body resistance exercise system (which would be TBRE). But he used a logo that looked like an X with a head. Total body is the T, resistance is the R and then the X-man is the X (not to mention exercise). Hence, TRX. Which sounds much cooler than TBRE anyway, right?

Coming to Terms

The straps have evolved since that first deployment in 1997, with adjustability, an instantly recognizable black and yellow color scheme and more.

” ‘Suspension training’ wasn’t a phrase thirteen years ago,” Hetrick points out. “I kept trying to explain to people how this thing worked. There was no precursor.”

Hetrick would explain it by saying, “your body weight is partially suspended, partially supported because one end of your body was on the ground.” And once he started calling it suspension training, it caught on. The number of certified TRX trainers has grown tremendously and now numbers more than 320,000.

The best part about the TRX straps may be how people use them, which keeps changing and evolving.

“It’s something different to everyone, depending on your ability, your interests [and] your preferences,” Hetrick says. “Some people like plyometrics. Well, this is a great plyometric tool. Other people like Pilates. [The TRX] is a great isolative tool.”

Considering it was created for commandos and some of the toughest people in the world, Hetrick finds it funny that it has become one of the biggest and most popular senior fitness tools.

His reaction to such a development probably sums up his overall feeling about how big his product has become since those cramped warehouse days: “I did not see that coming.”