A version of this article originally appeared in Gear Patrol Magazine with the headline “The Review: The North Face FutureLight.” Subscribe today

In 2017, after summiting 14,000 feet to the peak of Colorado’s Mt. Sneffels, Andres Marin turned to Scott Mellin, holding a sweat-soaked layer he’d just peeled off his back, and asked something to the effect of, “Wouldn’t it be great if we didn’t have to do this all the time?”

Any mountaineer, rock climber, backcountry snowboarder, resort skier, hiker, runner or bike commuter can describe the unpleasant clamminess that percolates inside a waterproof shell under hard exertion. But Marin, a professional climber for The North Face, and Mellin, the company’s Global General Manager of Mountain Sports, were in a position to do something about it.

Less than two years later, The North Face is releasing its first collection featuring FutureLight, a new and potentially revolutionary waterproof fabric technology that the company has been teasing for the better part of 2019.

The dream of FutureLight is simple, which is not to say easy: waterproof technical apparel that’s so breathable the wearer remains dry inside and out, even during serious effort. Every outdoor brand from Patagonia to Arc’teryx has been trying to solve this riddle for years; the breathable-waterproof conundrum has remained the Gordian Knot of the outdoors industry.

To make a fabric that lets sweat escape while still keeping rain or snow out, materials companies have long relied on substances like polyurethane and polytetrafluoroethylene, or PTFE. Gore-Tex, for example, makes its Pro membrane from a sheet of PTFE stretched to just .01 millimeters thick, with roughly nine billion pores per square inch. That’s small enough to prevent a water droplet from sieving through but plentiful enough to let body vapor out — up to a point.

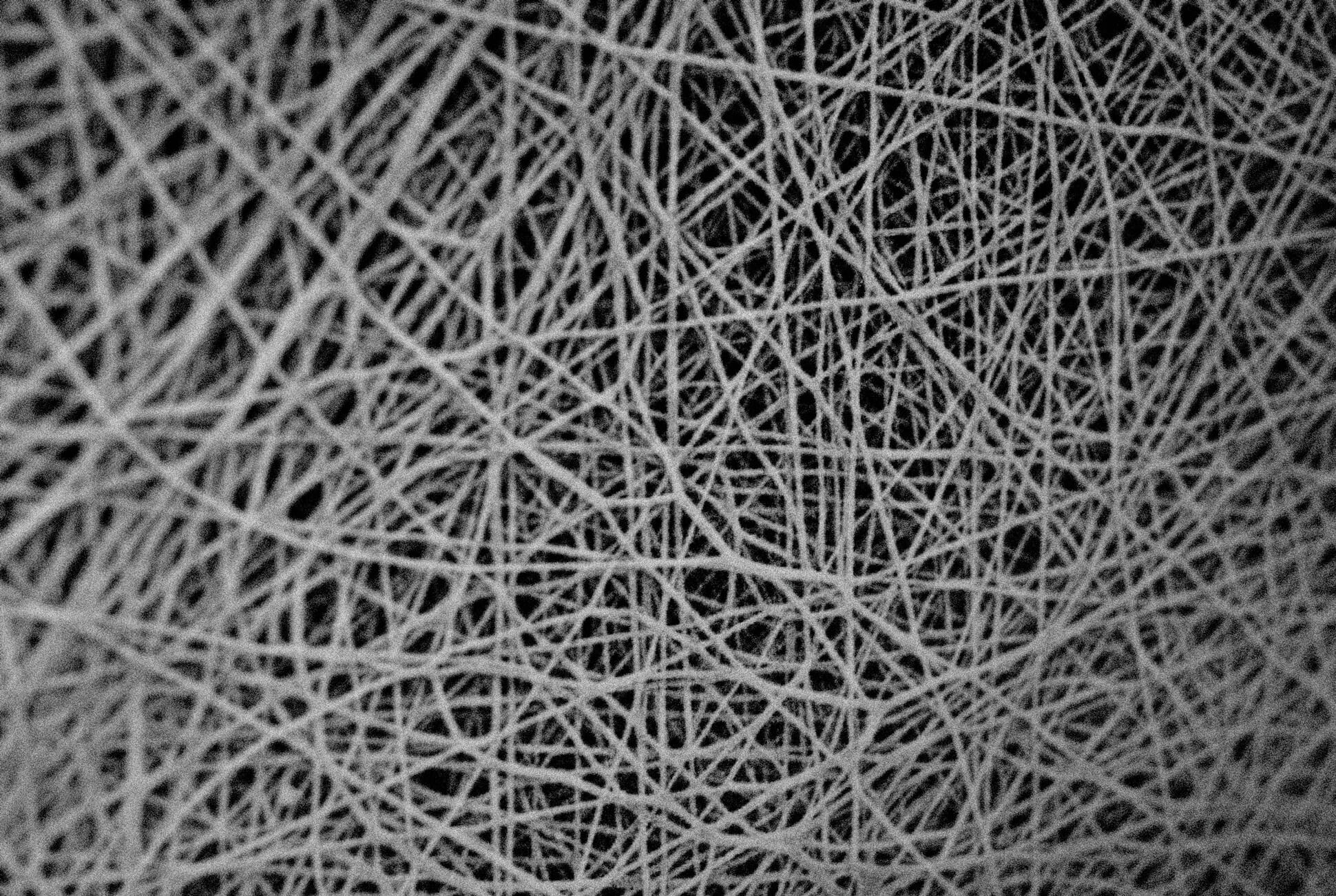

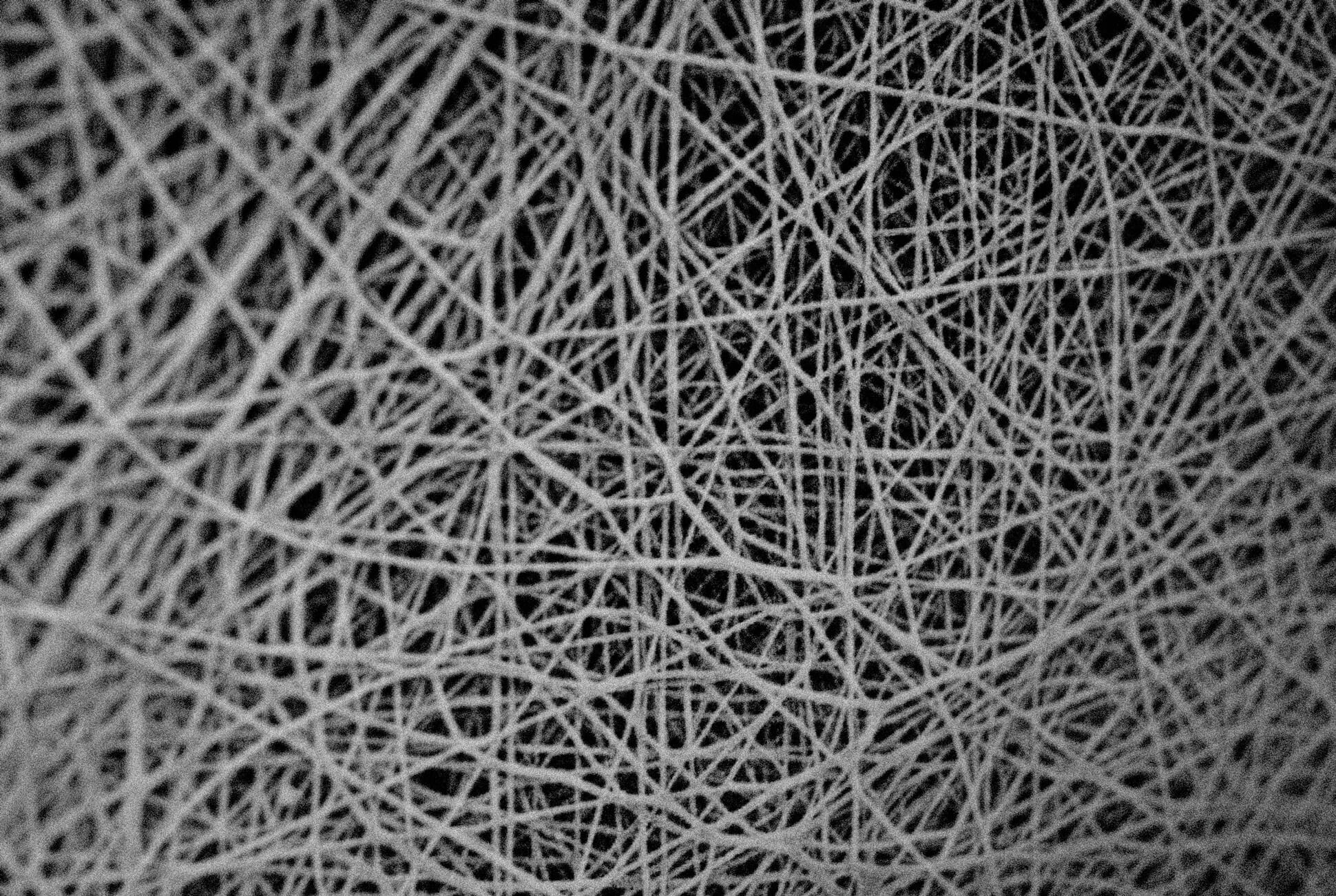

FutureLight features a polyurethane manufactured through nanospinning, a process already used in technology and medical fields. The polymer starts as a liquid solution that gets drawn through over 200,000 nanosized nozzles to create indescribably thin threads that are then layered into a mesh-like pattern of crisscrossed fibers and intervening gaps.

Roughly 4,300 feet later I reached Ski Hayden Peak’s 13,316-foot summit, damp but not drenched, and very comfortable.

The North Face claims an ability to “tune” the membrane to create more or fewer of these gaps, increasing or decreasing a fabric’s breathability. This allows the company to craft FutureLight-equipped garments for wildly different activities, from urban running to off-piste skiing. I got a chance to test the stuff last winter, in Aspen, on peaks not far from where Marin and Mellin had their epiphany.

I’m attuned enough to know I run hot, so I typically start a climb wearing little more than a long-sleeved base layer, even when temperatures are in the teens: I’d rather start chilly than strip layers mid-ascent as I begin to sweat. But, for the sake of testing the new fabric, I donned both a base layer and a light fleece under The North Face’s A-Cad Jacket and bib, two products admittedly designed more for downhill than uphill use.

Previous experience insisted I was overdressed, but roughly 4,300 feet later I reached Ski Hayden Peak’s 13,316-foot summit, damp but not drenched, and very comfortable. I didn’t have to start the climb cold, and I also didn’t have to futz with layers in the summit wind. All I had to do was zip up my armpit vents.

FutureLight recently debuted in jackets and pants designed for skiing, snowboarding, alpine climbing and other cold-weather, high-elevation activities; next spring it will weave its way into new windbreakers, rain jackets and footwear. Recently, I stumbled into the perfect urban test for the forthcoming Arque Active Trail FutureLight Pullover rain jacket: a New York City downpour on the way home from work.

Aboveground, rain fell in sheets while below, the subway became a sauna. Wearing a rain jacket on a steamy subway car usually means a sweat-soaked shirt, but when I arrived home after the half-mile walk from the station, the only dry bit of fabric on my body was my shirt.

After more than half a year of sporting FutureLight for climbing, skiing and trekking around town, the largest dilemma I can identify is the need to rethink my layering entirely. Because the A-Cad jacket is so breathable, I have to wear more than usual to stay warm inside of it. Other early testers have suggested these new materials are more wind-permeable, which makes sense, though I didn’t experience that myself.

Some also point out that, despite TNF’s marketing push, nanospun membranes are not new. The technology was introduced most notably in Polartec’s Power Shield Pro and NeoShell fabrics, which debuted in 2009 and 2010, respectively, though with far less fanfare. The North Face concedes the membrane construction is similar to past products but notes points of differentiation in the process — notably, the brand developed its own machines to produce the material in a factory that makes electronic insulating elements outside of Seoul, South Korea.

But the unquestionable difference will be scale: the sheer variety of products that will come equipped with FutureLight from a brand of The North Face’s stature (the company’s annual revenue tops $2 billion) immediately raises the material’s profile — and application — across the board. By the end of 2020, every waterproof garment the brand produces will feature the stuff. That means, whether consumers are buying products for FutureLight or just the TNF logo, that FutureLight is destined to find its way onto city streets and backcountry trails across the globe. Not bad for a product born out of a sweaty conversation between two friends on top of a mountain.