Editor’s Choice: Fuji GW690III

Editor’s Choice: If the Mamiya 7 II is too far out of your price range, get this. The Fuji GW690III is a rangefinder-style camera, just like the Mamiya, but offers slightly lower-grade optics and a greatly reduced price. It is known as the “Texas Leica” because of its hefty build quality and size. The other thing that the Fuji has going for it over the Mamiya is its massive 6 x 9 negatives. This giant negative size translates to higher-quality images and the ability to print them larger if that’s your jam.

Introduction

Film: recording moments. Moments that have passed, even as the shutter clicks. It’s no wonder photography is bound so deeply to nostalgia, sending us down memory lane to simpler times. But the hobby — the art — is deeper still; the equipment you use says just as much about your craft as your subjects or the developed, framed end product. For many, that sense of history is best captured and enjoyed through a vintage camera context, and believe us, there’s no shortage of those on the market. So here’s our help: a list of 24 cult vintage shooters that’ll help you find your creative eye, set you apart from the shutterbug crowd and still produce photos that’ll make your (less talented) friends and family envious.

Additional reporting by Chris Gampat, AJ Powell, Henry Phillips and Tucker Bowe.

Why Shoot Film?

The Cost Effectiveness

I know this first one sounds like a joke but bear with me. Medium-format film has a bunch of really interesting advantages over puny 35mm roll film (and digital DSLRs). The depth of field is better because of the larger film area, images are sharper because they’re usually scaled up less than 35mm (they can subsequently be enlarged way more), and thanks to some optical trickery they more closely emulate what the world looks like to the human eye. A roll of medium-format film has 12 frames and costs about $10 to buy and develop. Shelling out nearly a dollar per picture might seem unbelievably expensive until you consider the digital alternative.

If you want to shoot medium format digitally, get ready for some sticker shock. A mid-range digital medium-format camera will run somewhere in the neighborhood of $15,000; an excellent one will be closer to $30,000. That’s the cost equivalent of a film-based Hasselblad 500C/M and 2,800 rolls of film. In fairness, you’ll need to buy a good scanner to get the best of your film shots, but even including that it’s still a significant savings unless you’re shooting a lot and getting compensated well for it. So concrete reason number one why I’m in love with film? I can get the amazing results of medium-format photography without auctioning off naming rights to my first-born.

The Re-Education

Every DSLR has a manual mode and manual focus, but — be honest — how many times have you used it while shooting day to day? Picking up a fully manual camera got me back to high school photo classes and reminded me of rules of thumb like “Sunny 16” and guide number flash distance. Stuff that I had completely forgotten came back quickly as I tried not to throw away money on muffed exposures. These days when I pick up a DSLR I still use autofocus and auto exposure, but I feel more aware of what the camera is doing and why — plus I’m able to change it if it’s wrong.

The Gear

It was hard to not be stoked when I got to use two iconic cameras that both cost less than a quality Canon DSLR lens. As far as quality per dollar, you can’t beat a lot of old film cameras. Hell, a good-condition Leica M6 body can be had for $1,500 and that’s one of the most legendary cameras you’ll ever find.

The Post-Processing

One of the best parts about film is that things look so great right out of the camera. Fuji and Kodak have spent years and millions of dollars perfecting their films for beautiful levels of contrast, grain and color so all you have to do is focus and expose. Sure, you can edit your scans in Photoshop like everything else, but you really just don’t need to (save for some exposure stuff here and there). Compare this to shooting in digital RAW — where the whole point is that images look like shit out of the camera and absolutely need post processing — and you can see why it’s so relieving not to spend hours in Photoshop adjusting color balances and tone curves.

The Thrill

This, like describing why you should do a kale juice cleanse, is the one that gets the most eye rolls when I try and describe why film’s great. And maybe I just have to concede and sound pretentious for a second. It’s really fun to shoot a roll of film, and that’s half because you have no idea what you’re going to come out with (if anything). The black box magic of photography is back. It isn’t a staid combination of ones and zeros that can be checked and adjusted ad infinitum, but rather light coming in and freezing little chunks of silver halide forever like Arnold Schwarzenegger. You won’t get to see the results until the moment has long passed — and that’s pretty scary if it’s something important. It’s a little bit random and a little bit terrifying, but so rewarding when you get it right. And that’s the thing about film: you can talk about it endlessly and rationalize it with however many hundreds of words, but until you load a roll and give in to the haphazardness of this 200-year-old chemical process, you’ll never quite know what everybody else is on about.

Vintage Cameras 101

Where to Buy

eBay: No-brainer. It’s the biggest, it’s the best, but it can also be a bit daunting. Start your search here.

KEH: Buy, sell, trade, repair — when it comes to vintage cameras, KEH does it all.

Buying Tips

1. Do your research. Read this post, where our camera boffin has done the legwork for you. Read other sites. Read forums. Make sure you find some common prices before taking the plunge.

2. Skip the pawn shops. And Craigslist, unless you’re a pro.

3. Film, duh. You’re going to need some film. Check out our buyer’s guide at the end of this post for some suggestions.

4. What to look for: Typical problems areas that you’ll want to make sure are working: light meter, shutter, film advance, viewfinder, light seals (though imperfect ones might make for interesting shots), controls, lens.

Point and Shoot

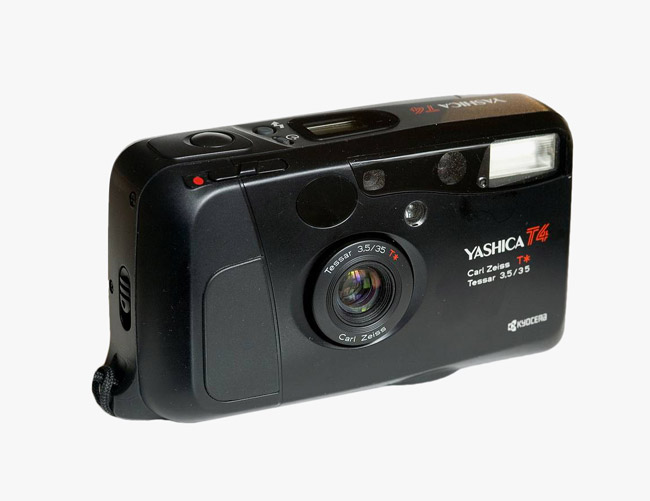

Our Favorite Point and Shoot: Yashica T4

When discussing the Yashica T4, you’ll find it’s really all about the lens. Its fantastic 35mm f/3.5 Zeiss Tessar lens is far and away better than the lenses found on many of today’s top-end digital compact cameras. Aside from the lens, however, the T4 is a fun, simple and relatively cheap compact camera, great for taking to house parties and day adventures. If you want example photos, Google “Terry Richardson” — he’s made it famous.

Konica Hexar AF

The Hexar AF can arguably be called a fixed-lens, autofocus rangefinder. However, many may refer to it as a point-and-shoot. So how did a point-and-shoot become a cult classic?

The lens, a 35mm f2, rumor has it, was an exact copy of the Leica 35mm f2 Summicron for M mount cameras without the nosebleed price. Sprinkle some magical autofocus capabilities onto said lens and attach it to a compact camera body — you’ve got yourself a camera that can live in the inside pocket of your 1968 Vintage Bomber jacket. In English, this means it is perfectly aimed at the street photography audience.

Couple this with the quiet shutter and film advance, and you’ve got a load of reasons why the Hexar AF was (and still is) a cult classic. The camera comes with its caveats though; manual controls are a bit cumbersome. Thankfully, there is a built-in light meter, so judging exposures is a cinch. These cameras can be very pricey but usually stay under $1,000, which is much more affordable compared to an M-Mount Leica 35mm f2 lens.

SLR

Our Favorite SLR: Nikon F2

For a 35mm camera, it doesn’t get much better than the Nikon F2. It features interchangeable viewfinders, so if it breaks, it’s a simple fix. This F2 also works with almost any Nikon lens (we recommend checking compatibility here first) because Nikon has never changed its lens mount. Pair the F2 with a Nikkor 50mm 1.4 lens, and you have a street-photography setup ready to take on cities around the globe.

Nikon FE

We’d be remiss if a Nikon 35mm SLR didn’t show up on this list, and the FE is one of our favorites for its combination of reliability, low cost and compact size (especially compared to its F2 and F3 brothers). Nikon is famous for over-engineering its film SLRs, and the FE is no exception; the alloy body and precision manufacturing mean that even though you’ll be spending less than $100 on the body, you won’t be getting something disposable. The FE was intentionally designed as an advanced enthusiast camera that eschewed electronic gimmicks, so you’ll want to brush up on your aperture and shutter speed knowledge before loading a roll in order to get the most out of it. Combine its rugged simplicity and low cost with nearly universal Nikon F-mount lens compatibility, and you’ve got the perfect camera for diving back into film.

Pentax K1000

The Pentax K1000 exuded simplicity and reliability, and was widely used for a very long time. Many people shot the K1000 for both professional work and for hobby; but even until recently many students sought it because of its affordable price, sturdy body, excellent light meter and small size. Sling one around your torso with a single prime lens and you can shoot all day and night.

The K1000 has a very vintage appeal about it because of its chrome- and leather-covered body. Focusing the camera requires lining up two images in the split-prism viewfinder. Pentax still manufactures a number of interesting focal length lenses such as 31mm, 43mm and 71mm — and any Pentax fan will speak volumes on their quality. Fortunately, the K1000 also hangs on the budget-friendly side of the spectrum. If you’re making the initial journey into film photography, this is the vintage shooter for you.

Canon AE-1

The Canon AE-1 is arguably one of the first film cameras to make photography simple and more accessible to the masses. Your parents probably used one to photograph all those embarrassing shots of younger you in your Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles get-up (way before Michael Bay tried to ruin your childhood). By giving users a full-program auto mode, shooting quite literally turned into a point, focus and shoot process.

So why did it find its way into the hands of enthusiasts, families and more? Besides being so simple your grandma could use it, Canon (and third-party companies) supported it with loads of accessories and lenses. Today, you’ll find photographers behind its iconic body for professional work because of the excellent FD mount lenses available, such as the 50mm f1.2. They’re also very well built and quite obviously withstand the test of time.

Canon A2/A2e

Rounding out this list is the Canon EOS A2, which was the first camera to have what some photographers still yearn for: eye-controlled autofocus. The film predecessor to the 5D series of cameras earns a place in the revolutionary cameras database for including this feature. The user could use their pupil movements for focus and other features like depth of field preview by simply looking at the top left corner of the viewfinder. But those wearing glasses couldn’t use it, which inevitably brought back horrible memories of “four-eyes” taunts. The feature also only worked if you held the camera landscape style — which meant it was perfect for your Grandpa photographing you terrorizing your sister in the backyard. Still, the pure technology behind the feature is something that should be rekindled in today’s world.

Rangefinder

Our Favorite Rangefinder: Plaubel Makina W67

The Plaubel Makina W67 is regarded as one of the best medium format rangefinders ever made. It shoots photos in a 6 x 7 format (hence the “67”) and is equipped with a fixed 55mm Nikkor lens, which is considered one of the best lenses in all of analog photography. It offers a wide field of view that’s roughly equivalent to a 23mm lens on 35mm format. This is the ultimate grail of vintage cameras.

Fuji GW690III

If the Mamiya 7 II is too far out of your price range, get this. The Fuji GW690II is a rangefinder-style camera, just like the Mamiya, but offers slightly lower-grade optics and a greatly reduced price. It is known as the “Texas Leica” because of its hefty build quality and size. The other thing that the Fuji has going for it over the Mamiya is its massive 6 x 9 negatives. This giant negative size translates to higher-quality images and the ability to print them larger if that’s your jam.

Rollei 35 S

The Rollei 35 S is, to this day, one of the smallest 35mm cameras on the market. Kitted with a Zeiss Sonnar 40mm 2.8, the tiny viewfinder camera packs a serious punch. It is small enough to easily fit in a pocket, making it easy to transport and great for capturing candid snapshots.

Contax G1/G2

The Contax G1 is a titanium-clad, Japanese-made marvel that was introduced in 1994 as a high-end electronic rangefinder to compete with Voigtlander and Leica, and became host to some of the best camera lenses ever made. The Zeiss lenses made for the G1 (and its 1996 G2 revision) are all as good, if not better than their Leica equivalents with the 45mm f/2 and 90mm f/2.8 deserving the most praise. The G2 revision offers a bigger body, redesigned button layout, a better viewfinder (the G1’s is about as bad as they get) and improved autofocus. The G2 has driven most of the resurgence, and as a result, its body will cost something like $600 instead of the G1’s $100.

Regardless of whether you buy the G1 or G2, you can be sure that you’re getting one of the absolute best optics systems ever made and a reliable, workhorse 35mm rangefinder.

Leica M6

Leica cameras list amongst those coveted by many and owned by few. When the Leica M6 appeared, many people thought it was one of the most perfect M cameras ever made. It became one of the first full M cameras to include a working built-in light meter while keeping the size down (the Leica CL could also attest to this claim, but it lacked the feature set; the Leica M5 included a meter built in, but physically towered over every other M camera made). Not only that, but reading the meter became simplistic, as the LED arrows in the viewfinder conveyed the over- or underexposure.

The M6 included frame lines for lenses as wide as 28mm — which many rangefinder aficionados clamor for. The cameras themselves are designed for documentary and photojournalistic work, and most people don’t reach for lengths beyond 50mm. So when you’re pondering lens options, remember to tell your friends to fix their hair, because you’ll be getting quite close.

Leica M6 cameras still sell for a lot of money, and the lenses can rack up an even more costly price tag in the long run. Owning one means you’ll have your hands on a piece of history, but history that will last (the handmade German engineering that defines Leica includes precious care and various quality control checks). Voigtlander manufactures some very good and affordable alternatives, though, and they can introduce you into the Leica world.

Mamiya 7 II

The Mamiya 7 II utilizes a leaf shutter (which means that the shutter is actually in the lens) that can sync flash speeds to 1/500th of a second. But what also made the camera so famous is its ability to use wide angle lenses. It mainly shoots in the 6×7 format, though other sizes can be used to capture vast structures and scenes. The rangefinder looks bright and beautiful with very highly visible frame lines.

Most importantly though, this camera launched as one of the most quiet-firing on the market (and we’d even say it continues to hold the title today). Sometimes you can take a picture and not even know that the shutter fired. The Mamiya 7 II will steal the hearts of landscape and wedding photographers. Eventually, it may become the only camera you’ll ever need. Want one for brand new? Unfortunately, you can’t expect it to be cheap.

The Tech Dopp Kit 2.0 from LA-based brand This is Ground is the perfect way to keep your camera gear and other travel tech neatly organized. Learn more about it and find other amazing products in the Gear Patrol Store.

Medium Format

Our Favorite Medium Format Camera: Mamiya RZ67

Studio and wedding photographers should look no further than the Mamiya RZ67. While it’s not very portable (with the 110mm lens it weighs over five pounds), it offers convenience and excellent quality. Its changeable film backs can be preloaded with color or black-and-white film. And the backs also rotate to allow you to switch between landscape and portrait orientation without moving the camera or tripod.

Yashica Mat 124G

Compared to other twin-lens cameras like the Rolleiflex, the Yashica Mat 124G is a steal. It’s a great beginner medium format camera that’s available in two lens formats, a 75mm and an 80mm. The 75mm 3.5 Lumaxar taking lens is said to have been made in West Germany, and is of the Tessar type, making the optics and quality nearly identical to that of the Rollei.

Zenza Bronica ETRS

Think of the ETRS as the little brother to the RZ67. They boast many of the same features, but the ETRS is considerably smaller and lighter. It works great as a studio camera, but can easily make the transition to on-the-go street-style photography. It comes in a variety of lens configurations, all of which feature leaf shutters. Be careful when buying lenses, as the leaves are prone to jamming up from oils or fungus.

Kiev 88

Also known as the “Hasselbladski,” the Kiev 88 is essentially a knock-off Hasselblad 1600 F. The camera was produced in the Arsenal Factory in Kiev, Ukraine, and is an excellent alternative to the more expensive Hasselblads (though some models are believed to have been poorly produced during certain years). The Kiev 88 is also compatible with one of the best fisheye lenses available, the Arsat 30mm f/3.5, which can be found for around $200, making for a rig that’s worth its quirks.

Pentacon Six TL

The Pentacon Six is a German-produced SLR-style camera built to shoot 120 film. It’s modeled after the convenience of 35mm cameras, with a similar layout and function. The TL in its name designates a metered prism viewfinder, though non-metered versions are also available. While the Pentacon Six is quite a bit larger than a standard 35mm camera, it’s still comfortable to wear around your neck.

Pentax 67

The Pentax 67 is a monster of a camera. Its beefed-up SLR body weighs more than five pounds and a special-accessory wooden hand grip is pretty much required for hand holding. The sound of the mirror coming before an exposure is enough to start an avalanche. Though it’s a beast, the upsides of the SLR design are easy to spot. Pentax has made a huge variety of lenses to match any scenario (and the 105 f/2.4 standard lens is a gem), since the body style is relatively simple they can be had for cheap on eBay (look for the 6×7 MLU, 67 and the updated 67ii; avoid the oldest ones marked just “6×7”) and they’re no more complicated to use than any 35mm SLR. Because of their ubiquity and panzer-esque reliability, they’re still widely used for fashion and studio work while also providing a cheap gateway into oversized film.

Hasselblad 500C/M

The Hasselblad 500C/M makes for some very happy photographers with its stunning good looks and gorgeously vintage aesthetics. With a look-down-style viewing screen and a lovely hand crank on the side to advance your film, you’ll have a lot of fun using this baby. Despite how much fun and experience you’ll accrue, the original design targeted professional work, and Hasselblad’s prices clearly communicate that. The company has often been deemed the Rolls Royce of cameras.

Still, the optics and image quality rank among the top of the hill; many photographers rely on the 500C/M even today for their paid contracts. So if you’re dead set on a Hasselblad, we’d recommend ensuring that your photography skills rank above an amateur level.

This Hassy uses 120 film, which trumps 35mm in size and therefore gives you more bokeh, that beautiful blur that you see in so many photos these days. Coupled with some of the new Kodak Portra film, which the company designed for scanning, you’ll eventually create an online portfolio to be truly proud of. The combo will yield you prints well worth hanging up in your living room after being printed on white glossy aluminum.

Contax 645

Fast-aperture Zeiss glass? Check. 120 film in the 645 format? Check. Autofocus? Check. The ability to one day go medium-format digital? Checkmate.

Ask any medium-format photographer and they’ll tell how they feel about the Contax 645. Before digital became mainstream, this medium-format beast was in the hands of the crème-de-la-crème of wedding photographers and portrait-shooters. In the hands of an experienced snapper, it came across as simple to use, had autofocus with lenses as fast as f2 (which is extremely shallow in medium format due to the larger negative size), and could probably knock a thief out cold if one tried stealing it from you.

They are still highly sought-after but very rare; finding one is quite honestly like snagging a unicorn. And if you can find one in perfect working condition with an 80mm f2, 120 back and an AE prism, pony up the Benjamins.

Instant

Polaroid SX-70

If there is one Instant Film camera that will stand out in the minds of many people, it is the Polaroid SX-70. There’s a very good reason why this cult classic is in the hands of every hipster you know.

Sporting leather exteriors trimmed with metal, the camera folds down for compact storage and unfolds easily enough to snap a cat before it can escape (the sneaky bugger). Using the bright viewfinder, the user can manually focus the lens, and as long as the light meter next to it isn’t blocked, a beautiful piece of vintage analog love is always printed out right on the spot. Today, you can still get film for the camera from the Impossible Project — who have come a far way in developing and improving their formula. Be sure that you can snag one in good condition with no holes in the bellows.

Large Format

Horseman 4×5

If you’re looking to get into large format studio photography, a Horseman 4×5 is an excellent choice. There’s a host of lenses available (some of the best examples are made by Schneider) that mount onto lens boards sized specifically for your camera. The Horseman 4×5 also allows for the lens to be moved independently of the film back; this means that you can get some really funky planes of focus, which some might know as “tilt shift.” (Yep, before it was a tool on Instagram it was a physical process used to obtain an interesting field of view.)

Graflex Speed Graphic 4×5

This classic 4×5 film camera dates back to the 1940s. Unlike the above Horseman 4×5, which was a whole process to set up and carry, this was actually a portable large format camera. In fact, back in the day, it was the camera of choice for many traveling photographers and paparazzi. If you’re looking to get into large-format film, these cameras are great, are available with a host of different lenses and can be found for a relative steal.

Now, Get Some Film For Your New Camera

Color Negative

|

Kodak Portra Portra is everywhere. Kodak’s most popular roll film is available in 160, 400 and 800 ISO but the 400 is the most versatile of the bunch, easily coping with being under- and over-exposed without getting too grainy. Portra of all speeds renders skin tones beautifully, scans better than most films and has an incredibly pleasant grain structure. Available in everything from 35mm rolls to medium format to sheet film, the 400 is our go-to when we need a color film on any shoot. $6+ (per roll) |

|---|---|

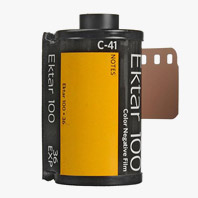

|

Kokak Ektar 100 Ektar is another gem from Rochester. It boasts more saturation and contrast than Portra and an amazingly fine grain structure. As a result, pictures tend to not look all that “film-y”, which can be a good or bad thing depending on what you want. It’s only available in 100 ISO, so you’ll need quite a bit of light, but the sharpness you’ll end up with is amazing. $6+ (per roll) |

|

Fujicolor Pro 400 Fuji negative films have always had a distinctive look that’s attracted loyalists. Compared to Kodak, Fuji usually has a slightly greener, slightly colder tone (compare the example links for Fujicolor and Portra to see what we’re talking about) that usually injects a bit more emotion into a given picture. Fujicolor Pro is a great film to keep in your bag if you’re looking for more contrast and moodier colors compared to Portra. Just be prepared to pay nearly twice as much for the privilege. $10 (per roll) |

Color Reversal (Slide Film)

|

Fujichrome Provia 100F Ever since Kodachrome was retired at the end of 2010, Fuji has been the only game in town when it comes to true slide film (though Ektar does a pretty good job mimicking it). Luckily, they’re doing a damn good job. Slide film is characterized by strong, saturated colors, sharp contrast, fine grain, a more fickle exposure range (slide film can usually only be recoverable when under- or over-exposed by one stop compared to negative film’s three or four) and, of course, a color-positive film. Provia is Fuji’s more neutral option with natural colors and less contrast than their vibrant Velvia. You’ll need a lot of light and a good exposure, but the results are some of the best you’ll find for general-purpose shooting. $10 (per roll) |

|---|---|

|

Fujichrome Velvia 50 When people talk about slide film these days they’re almost always talking about Velvia. The strong contrast, strong color film has taken over Kodachrome’s place as the low-ISO choice for those wanting amazing results right out of the camera. It’s great for landscapes and still life but isn’t the best at reproducing skin tones because Fuji’s typical greenish-purplish cast is even more pronounced in Velvia. $12 (per roll) |

Black and White

|

Kodak Tri-X 400 Think of any iconic black and white photo you’ve seen; odds are it was shot on Tri-X. Kodak’s hallmark black-and-white film has been around forever and its easy development, good-looking grain structure, perfectly balanced contrast and killer shadow detail mean it won’t likely leave the throne soon. If you’re going to start developing your own film or just want a great medium-speed black-and-white film, Tri-X is the easy choice. $5 (per roll) |

|---|---|

|

Ilford Delta 3200 Boasting three extra stops of light sensitivity over 400 speed film (that’s going from 1/15 shutter speed to 1/120 at a given aperture), Delta 3200 is the only choice when you need a super-sensitive low-light film. The grain is definitely pronounced, but if it’s exposed right the grain is minimized into a really pleasing pattern that’ll leave no doubt what film you shot on. $13 (per roll) |

|

Ilford PanF 50 Just the opposite of Delta 3200, PanF 50 is the perfect black-and-white film when you have light to spare and want sharp images with minimal grain and excellent dynamic range — showing detail in the darkest and lightest portions of an image. Simply put, if you want the highest-resolution black-and-white film, this is the one you want. $12 (per roll) |

From cameras with multiple lenses to one with a built-in digital projector, these are the most unique digital cameras available. Read this story